theartsdesk in Baku: Festival puts 'Azerbai-where?' on the map | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Baku: Festival puts 'Azerbai-where?' on the map

theartsdesk in Baku: Festival puts 'Azerbai-where?' on the map

Azeri festival in London shines a light on a culture which straddles East and West

It’s a rare national culture festival that presupposes its audience will have no knowledge whatsoever of the culture concerned - or even be able to locate the country itself on a map. But that, we must assume from the “Azerbai-where?” promotional bus ads, was the starting point last November for organisers of the BUTA Festival of Azerbaijan Art, a series of very well-connected art and music events in London going on this month.

BUTA may have started as entertainment to accompany an oil and gas conference at the end of last year, but wider offerings so far have ranged from Azeri jazz to food. Its final month offers an introduction to the mugham, Azerbaijan’s unique musical form, and to the work of the composer Gara Garayev and the painter Tair Salakhov.

Baku, the Azeri capital, is often called a city of contradictions, a meeting point of East and West, of the ancient and the contemporary – and much of the same applies to the country’s culture, too. Baku’s Old City (pictured right), a compact walled centre dating from the 12th century, has cobbled streets and the landmark Maiden’s Tower overlooking the Caspian, and an architectural jewel in miniature, the Shirvanshah Palace, home of its first rulers. Beneath it, along the Caspian embankment, run the dignified boulevards of late 19th-century Baku, a period when oil attracted the likes of the Nobels and the Rothschilds and brought the city fantastic wealth and strategic importance, as well as put a Western stamp on its buildings and habits. Azerbaijan, the “land of fire”, had moved on from a Zoroastrian past to petroleum.

Baku, the Azeri capital, is often called a city of contradictions, a meeting point of East and West, of the ancient and the contemporary – and much of the same applies to the country’s culture, too. Baku’s Old City (pictured right), a compact walled centre dating from the 12th century, has cobbled streets and the landmark Maiden’s Tower overlooking the Caspian, and an architectural jewel in miniature, the Shirvanshah Palace, home of its first rulers. Beneath it, along the Caspian embankment, run the dignified boulevards of late 19th-century Baku, a period when oil attracted the likes of the Nobels and the Rothschilds and brought the city fantastic wealth and strategic importance, as well as put a Western stamp on its buildings and habits. Azerbaijan, the “land of fire”, had moved on from a Zoroastrian past to petroleum.

For a fictional glimpse into that old world, there’s nothing better than Kurman Said’s novel Ali and Nino: A Love Story (its exact authorship remains a matter of some contention to this day). There the ancient life of Baku’s nobility, closely connected with Eastern traditions - especially Persia - encounters the present day, not only in the form of the Western states, but finally the encroachment of Soviet power in 1920, which would trample, or change out of recognition, long-established traditions over the next 70 years.

As for what was left at the end of that process, and its surreal further development through the 1990s, there’s the snapshot view of Gary Shteyngart’s 2006 novel Absurdistan, where the architecture has changed again – with the arrival of glass and concrete as Western capital sets up an outpost, regardless of the local instability around it.

Yes, there’s been a lot of building in Baku over the last 20 years, and when it’s not been commercial it’s been state-commissioned. With an income from natural resources, and a fondness for the grand gesture, Azerbaijan’s current president Ilham Aliyev is following his counterparts in the Gulf in setting Baku up as an international cultural destination (and enhancing his own legacy into the bargain); he has the advantage that Azerbaijan is secular enough for Western art to take a natural place there. It’s all, of course, under the patronage of Aliyev’s first lady Mehriban, and judging by recent comings and goings to Baku of former Guggenheim foundation director Thomas Krens, as well as French architect Jean Nouvel, an outpost of that cultural franchise looks highly likely to be a part of the game plan.

But it’s another spanking new cultural building that already graces Baku’s embankment, the House of Mugham, that’s a real symbol of the country’s attempt to link its oldest cultural traditions with modernity, in the shape of a sleek, state-of-the-art auditorium. Mugham music is centuries old, part of the Eastern and Arabic tradition, which sometimes earns comparison to the Indian raga; it features in the London BUTA festival on Tuesday with an evening of Mugham and folk songs in St Martin-in-the-Fields.

A single concert can offer only a tiny view onto a whole tradition, which moves from the solo instrumental form (reflective, often melancholy), through to livelier ensemble playing, and the spirited, even overpowering addition of a vocal line of the kind that features in a proper Baku wedding.

A single concert can offer only a tiny view onto a whole tradition, which moves from the solo instrumental form (reflective, often melancholy), through to livelier ensemble playing, and the spirited, even overpowering addition of a vocal line of the kind that features in a proper Baku wedding.

Unlike some traditional music, Mugham continues to develop with the times: its rhythms and improvisational quality have filtered across into the likes of jazz (a form in which Baku has a very distinguished history), as well as today’s electronic-based offshoots. Certainly it long ago crossed over into the roots of Azeri classical music, which came to mix traditional sounds with the European symphonic tradition from the beginning of the 20th century.

Gara Garayev (or Kara Karayev, as his name was transliterated in Russian throughout his Soviet career) is the undisputed father of Azeri classical music. His career kicked off with a performance before Stalin of a key cantata written when he was only 20, through study in Moscow under Dmitry Shostakovich, on to domination of music in the republic as head of the Composers’ Union. His role as a functionary in Soviet cultural life may have obscured the scope of his talents, at least to the wider world. It’s a fate he shares with Tikhon Khrennikov, functionary supreme of Soviet music, and Armenia’s Aram Khachaturian, whose interest in native folk music Garayev shared.

His music is infrequently performed abroad, making the concert at Cadogan Hall concert on 28 February under the aegis of Gidon Kremer all the more special. Kremer is himself a champion of late Soviet-era composers whose heritage sometimes lies divided between their official and creative personalities. BUTA’s closing concert at the Royal Festival Hall on 7 March offers the chance to hear music by other Azeri composers that no one outside a very narrow circle will ever even have heard of.

Garayev died in 1982, having spent the last few years of his life in Moscow, for reasons that puzzled even his friends. Of his native city, the composer waxed lyrical in the much-quoted lines: “To me, Baku is the most beautiful city in the world. Every morning, when the city wakes whether it be to the sun or the rain and fog, every morning my city sings. Baku is meant for art. It gives me so much pleasure to write about this city no matter if you write music, verse or paint images.”

From Garayev the baton of national artistic treasure passed to visual artist Tair Salakhov, who is now in his early 80s. Salakhov’s work is on show as part of the BUTA festival at Sotheby’s from 18 to 25 February. The two men were close friends; Salakhov painted a landmark portrait of Garayev in 1960 (pictured, © Tair Salakhov). The world of music was always close to the artist, and his better-known portraits include one of Shostakovich, as well as Mstislav Rostropovich, himself Baku-born. In Baku a small museum with somewhat irregular opening hours commemorates the great cellist. Rather more typically for Baku (where if you hold a party, it’s got to be memorable), so does a grandious international music festival held the last two years to mark Rostropovich’s death in 2007.

From Garayev the baton of national artistic treasure passed to visual artist Tair Salakhov, who is now in his early 80s. Salakhov’s work is on show as part of the BUTA festival at Sotheby’s from 18 to 25 February. The two men were close friends; Salakhov painted a landmark portrait of Garayev in 1960 (pictured, © Tair Salakhov). The world of music was always close to the artist, and his better-known portraits include one of Shostakovich, as well as Mstislav Rostropovich, himself Baku-born. In Baku a small museum with somewhat irregular opening hours commemorates the great cellist. Rather more typically for Baku (where if you hold a party, it’s got to be memorable), so does a grandious international music festival held the last two years to mark Rostropovich’s death in 2007.

Salakhov’s early emergence as an artist in the period of Khrushchev’s post-Stalin “thaw” is associated with a movement away from the accepted tenets of Soviet realism, and involvement in what came to be known as the “severe” school; today, particularly for a foreign viewer, the distinctions of that time may seem less pronounced. He duly rose in his time through the Soviet arts hierarchy, too, to lead the Soviet Union of Artists from the late 1980s, when perestroika’s mood chimed with his own ability to bring landmark shows by foreign artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Francis Bacon to Moscow. Imposing images of his native Azerbaijan, with its natural fires, oil rigs and the like, remain a source of inspiration to younger artists. It seems there’s little escaping the oil industry for an Azeri creative (The Caspian Today, part of a triptych by Tair Salakhov, pictured below, © Tair Salakhov): on one occasion Garayev insisted on having his piano moved to a rig to help him compose a film score on the subject.

Salakhov, too, has long made Moscow his main home, raising the question almost 20 years after the break-up of the USSR of where the cultural reins that influence Azerbaijan’s artistic future are being wielded today. There was never any rapid attempt, like in the Baltic states, to throw out the Soviet bathwater and define an independent cultural identity (a couple of liberal-leaning years that might have attempted that from 1993 came to a bad end). Russian remains powerful as a language in literary and artistic spheres, and it’s not going away soon, even if with the young it’s gradually being replaced by English.

Salakhov, too, has long made Moscow his main home, raising the question almost 20 years after the break-up of the USSR of where the cultural reins that influence Azerbaijan’s artistic future are being wielded today. There was never any rapid attempt, like in the Baltic states, to throw out the Soviet bathwater and define an independent cultural identity (a couple of liberal-leaning years that might have attempted that from 1993 came to a bad end). Russian remains powerful as a language in literary and artistic spheres, and it’s not going away soon, even if with the young it’s gradually being replaced by English.

The word “buta” means “bud” in Azeri, and if this first festival has honoured the achievements of past greats, the hope must be that any such future showcase has rather more from younger generations. Its jazz offerings has certainly given a hint of that, as do a couple of photographic exhibitions. One of them (now closed, unfortunately) is by Baku-born Rena Effendi, whose Pipedreams: A Chronicle of Lives along the Pipeline followed the human consequences of the Baku-Ceyhan oil pipeline (linking the oil reserves of the Caspian to terminals on the Turkish coast and confirming Azerbaijan as a major independent player in the region). Effendi first caught the public face of the project officially for BP, but then she returned to look beyond it – into the worlds of those who may live in physical proximity to the pipeline, but whose traditional (and frequently very impoverished) lives remain little touched by it. (See the main image at the head of this article - visit her website here).

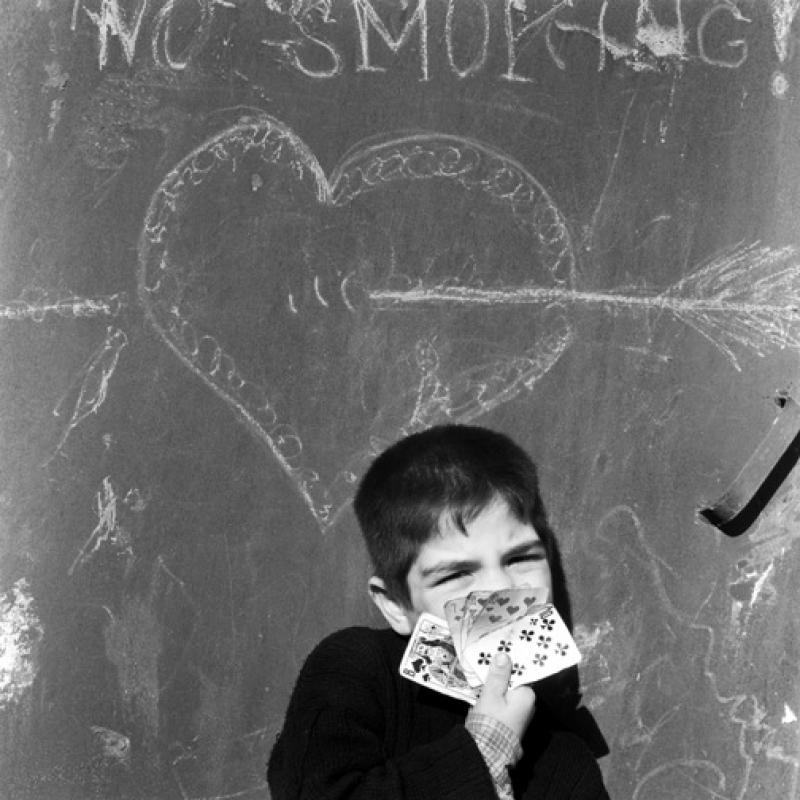

Russian photographer Alexander Mashin is showing work until the end of the month at St Martin-in-the-Fields, capturing sides of Azeri life that, one suspects, the country’s authorities might not be that keen to see publicised. To Western viewers they may be no more than scenes of neo-realism, like Children Playing Soccer in the Mountains (pictured © Alexander Mashin). Nine aestheticised black and white images from two refugee camps are testimony to the legacy of the war in Nagorno-Karabakh, and the fact that nearly 20 years on, a number of those who fled are still waiting for permanent rehousing (for many years, some refugees were held in train compartments).

From its beginning in 1988, the Karabakh war changed the face of Baku itself: the city’s long-established and considerable Armenian community was violently displaced. Baku’s impressive Alley of Martyrs is devoted to those who fell in conflict with Soviet forces in January 1990, as well as against Armenian troops, and has become a part of new Azerbaijan’s new ideology, a compulsory stop for any visiting dignitary. But the realities of present-day refugees are in very distinct contrast to such gleaming graves and memorials.

Effendi’s and Mashin’s very presence at the BUTA festival is encouraging, since such signs of relative dissent (whether against the state or against Big Oil) resound considerably more over there than viewers in the UK may understand. Here, the British Council and the like practically make a habit of exporting unflattering images of national identity; there, presentation of what might be seen as unofficial voices and visions is much more closely watched (however subtly the tools of surveillance may be wielded). At the end of a century in which degrees of conformism played a considerable role in Azerbaijani culture, the appearance of more independent views like these is deeply encouraging.

Events in the BUTA Festival include:

- Gidon Kremer's Evening of Symphonic Music by Garayev, Cadogan Hall, London, 28 February

- Gala concert, with the RPO and Schlomo Mintz, violin, in music by Amirov, Hajibeyov and Rzayev, Royal Festival Hall, London, 7 March

- Tair Salakhov's art is showing at Sotheby’s, London, 18-25 February

- Alexander Mashin's photographs of Azerbaijan are showing at St Martin-in-the-Fields, London, until the end of February

Comments

...