Éthiopiques: Mulatu Astatke and the Story of Ethiopian Jazz | reviews, news & interviews

Éthiopiques: Mulatu Astatke and the Story of Ethiopian Jazz

Éthiopiques: Mulatu Astatke and the Story of Ethiopian Jazz

Interview with key figures from Éthiopiques jazz cult

As the London Jazz Festival approaches, it's an unlikely fact worth noting that some of the bestselling instrumental jazz records of the last few years have been from Ethiopia. Ethiopian jazz composer Mulatu Astatke, now 66, is the best-known practitioner and enjoying an Indian summer. A key feature of the 2007 The Very Best of Éthiopiques compilation, once heard his music is not easily forgotten.

His signature vibraphone-playing jazz uses the distinctive five-note Ethiopian scale: it's jazz as if from a parallel universe, by turns haunting, romantic and sometimes a touch sleazy, as though the soundtrack to an exotic B movie involving spies and seduction. How his music got to be known is in considerable part due the efforts of an obsessive Frenchman called Francis Falcetto.

Falcetto was a promoter of music when he first heard Ethiopian music in 1984. As he explained when I met him, “A friend of mine was a stage manager for a theatre troupe who had been touring Africa and had bought an LP by Mahmoud Ahmed in a music shop in Addis Ababa. I was astonished - it seemed like some missing link of music. So I thought, what else is there? Even though I knew nothing about Ethiopia or Ethiopian music, it seemed a good place to investigate. So I got on a plane to Addis the next month and invited Mahmoud Ahmed to tour."

Since then, much of Falcetto's time has been spent on Ethiopian music. He has toured numerous times with Ahmed, who is at last being recognised as one of the world's great singers, winning a Radio 3 World Music Award among others in the process. Since 1997, Falcetto has been compiling a series of fascinating compilations, all called Éthiopiques, now numbering 27. The series, always well regarded, has in the last few years broken out of its cult following. British-based Indian singer Susheela Raman did a cover of a Mahmoud Ahmed song as the title track of her album Love Trap, and even has an "Ethiopian version" of Bob Dylan's "Like a Rolling Stone" on her recent album 33 1/3. But what propelled the music more than anything else was the use of the enigmatic jazz of Mulatu Astatke in Jim Jarmusch's 2005 film Broken Flowers. Jarmusch discovered his music through Volume Four of Falcetto’s Éthiopiques series, which was dedicated to Astatke. “He found me when I was playing in New York", Astatke says, "and told me he was a huge fan and used quite a lot of it for Broken Flowers. That was when so many people discovered my music – I know I owe him a lot.”

Listen to extracts from Broken Flowers:

Falcetto’s Éthiopiques series has some exceptions that fit into no rules – such as Vol 21 by the Ethiopian nun Emahoy Tsegue-Maryam Guebrou (see video below). Although dedicated to teaching at an orphanage, she found time to create a series of jazz-influenced, Neo-Classical compositions for piano. The music sounds as if Erik Satie had lived in East Africa. The material on Vol 21 is culled from two LPs that were released in 1963, when she was 40. Meditations on biblical themes and the beauties of nature were her favourite subjects. She is currently a nun living in Jerusalem.

Listen to Mother's Love by Emahoy Tsegue-Maryam Guebrou:

When Falcetto first went to Ethiopia in 1984, it was the year of famine and starvation. The country was governed by the Derg, a communist military junta that ruled from 1974 to 1987, which had imposed a curfew when it took power after Haile Selassie was ousted. "Aside from the problems with the famine, the curfew and the censorship were very bad for the music and the nightlife," says Falcetto. "I realised I had missed the great years of Ethiopian pop music."

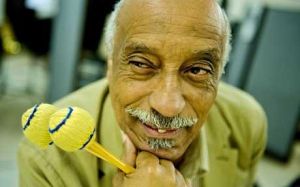

Some musicians, such as Astatke (pictured right), were drafted by the Derg in the 1970s to write stirring Socialist Realist tunes celebrating the achievements of the revolution. Most of the releases in the Éthiopiques series are from what Falcetto calls "the Golden Years" - the 1960s and early 1970s, the dying years of Haile Selassie's regime. These days, he says, while there is good folk music, and some of the religious music has ancient roots (the country was the first Christian country), the pop and jazz music scene is less interesting. Instead of big bands, there is often no more than a singer and a synthesiser in the clubs, hotels and restaurants of Addis.

Some musicians, such as Astatke (pictured right), were drafted by the Derg in the 1970s to write stirring Socialist Realist tunes celebrating the achievements of the revolution. Most of the releases in the Éthiopiques series are from what Falcetto calls "the Golden Years" - the 1960s and early 1970s, the dying years of Haile Selassie's regime. These days, he says, while there is good folk music, and some of the religious music has ancient roots (the country was the first Christian country), the pop and jazz music scene is less interesting. Instead of big bands, there is often no more than a singer and a synthesiser in the clubs, hotels and restaurants of Addis.

The year of Falcetto's visit was also the year of Band Aid. (Ahmed told me when I met him at the Radio 3 World Music Awards that he had shown Bob Geldof around Addis Ababa.) Geldof attracted considerable criticism for not using Ethiopian, or indeed African, musicians at Live Aid in 1985 and, 20 years later, at Live 8. Live Aid, asserts Falcetto, was bad for the music of Ethiopia. "It created this cliché, which Ethiopians are mortified by, of the country as a kind of desert where everyone is dying of hunger. It's a mountainous country that is quite green - the problems in 1984 were more to do with geopolitical struggles in the Cold War than anything else. And Addis is a sophisticated city, with plenty of rich people as well as poor."

Astatke also regrets Geldof's failure to book Ethiopian musicians. “I respect those people," he says, "but it made us look like a beggar, instead of us asking for help alongside our brothers and sisters in Europe and the States.”

Apart from its distinctive and rather oriental five-note scales, Falcetto suggests that what makes Ethiopia so unique musically is the fact that "unlike any other African country, it has been independent for 3,000 years, apart from the six years the Italians were colonists". Ethiopia was the first Christian country in the fourth century, and Church music from that time is still being performed today.

The only real outside influences in the 1950s and 1960s were big-band music from the States, including Glenn Miller, and later soul. Unlike elsewhere in Africa, the influences from Congolese and Cuban music didn’t apply to Ethiopia.

"Haile Selassie formed numerous brass bands for ceremonial purposes and they also played light music in the hotels," explains Falcetto. "The result was something wild - the biggest stars sang in police and army bands. Mahmoud Ahmed was a member of the Imperial Bodyguard Band for years." Alemayehu Eshete, often dubbed "the Ethiopian James Brown" (see video, below) was the star vocalist with the Police Orchestra.

Watch a video of Alemayehu Eshete performing:

Nowadays Falcetto is back in Toulouse. He has finally found what he thinks is a world-class Ethiopian-style band in Les Tigres des Platanes, a French jazz group whom he is recording alongside the Ethiopian singer Etenesh Wassie. Due to the Coptic Calendar the Ethiopian millennium was seven years behind the rest of us in 2007. As Falcetto puts it, "It's a little behind the rest of us in some ways, but the world is finally discovering how great the music of Ethiopia is."

I meet Mulatu Astatke in London. He is soft-spoken, and dresses smart with a slight air of the smooth operator and lounge lizard about him, as you might guess from his enigmatic, seductive music. He says his success has finally allowed him to record the music as he imagined it for his latest album Mulatu Steps Ahead: “Some of this music I was playing in small groups; now I have an orchestra and great musicians, I can put down the beautiful counterpoints and colours I always wanted to.”

The recognition has brought a shower of awards, including a fellowship at Harvard where he premiered a portion of his first opera, The Yared Opera, last year. He has been an advisor at MIT Media Lab in Boston: “I was developing Ethiopian instruments like the krar for the 21st century.” His new album seamlessly mixes bits of blues, salsa and boogaloo with his trademark scales and tones, a fusion that reflects his own history.

He first left Ethiopia in 1958 at 15 to study at Lindisfarne College near Wrexham in Wales. “I was supposed to be an aeronautical engineer. But then I realised I had to be a musician – my parents were not at all happy, as you can imagine.” Having been “a good soccer player in Ethiopia, they played rugby there. I was always on the wing, because I was so fast”.

In the holidays he would go up to London and hang out with older jazz musicians like Jamaican-born Joe Herriot. “There was a wonderful club in Soho called the Metro. Quite a lot of Nigerians and Ghanaians were there, playing their music. I used to sometimes sit in playing congas. Even then, I thought, why doesn’t anybody know Ethiopian music?” He persuaded his parents (his father worked in the Justice Department in Addis Ababa) to let him become a musician and he trained at Trinity College in London and then Berklee in Boston, before going on to New York, where he saw Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie at the jazz clubs and the likes of Tito Puente at the mythic Palladium Club. “You had to dance at these clubs – I became very good at salsa. It was a great place to have fun, drink and pick up girls.”

In the Sixties, he started producing his own music, which he dubbed Ethio-Jazz and released a couple of albums in New York before returning to Ethiopia where he set up his own band. “Mostly we were playing international music in hotels and weddings but I also presented concerts of Ethio-Jazz. To begin with people didn’t like it, but eventually the music got quite a following.”

When Haile Selassie took over in 1974 and introduced curfews, Astatke recalls that the damper put on the scene wasn’t quite as bad as Falcetto surmised. “The midnight curfew meant if you were in a club then you had to stay till five in the morning,” says Astatke. “So we used to have great jam sessions that lasted through the night.” As an instrumentalist with a distinct style, unlike other musicians with provocative lyrics, he didn’t fall foul of the authorities, who got Astatke’s band to play at official ceremonies. “I’m not saying I approved of the regime, but I just concentrated on making music,” he says, unapologetically.

Listen to "Mulatu" by Mulatu Astatke:

- Mulatu Astatke is touring Europe, including All Tomorrow's Parties in Minehead in December

- Find Éthiopiques on Amazon

more New music

Album: Paraorchestra with Brett Anderson and Charles Hazlewood - Death Songbook

An uneven voyage into darkness

Album: Paraorchestra with Brett Anderson and Charles Hazlewood - Death Songbook

An uneven voyage into darkness

theartsdesk on Vinyl 83: Deep Purple, Annie Anxiety, Ghetts, WHAM!, Kaiser Chiefs, Butthole Surfers and more

The most wide-ranging regular record reviews in this galaxy

theartsdesk on Vinyl 83: Deep Purple, Annie Anxiety, Ghetts, WHAM!, Kaiser Chiefs, Butthole Surfers and more

The most wide-ranging regular record reviews in this galaxy

Album: EMEL - MRA

Tunisian-American singer's latest is fired with feminism and global electro-pop maximalism

Album: EMEL - MRA

Tunisian-American singer's latest is fired with feminism and global electro-pop maximalism

Music Reissues Weekly: Congo Funk! - Sound Madness from the Shores of the Mighty Congo River

Assiduous exploration of the interconnected musical ecosystems of Brazzaville and Kinshasa

Music Reissues Weekly: Congo Funk! - Sound Madness from the Shores of the Mighty Congo River

Assiduous exploration of the interconnected musical ecosystems of Brazzaville and Kinshasa

Ellie Goulding, Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, Royal Albert Hall review - a mellow evening of strings and song

Replacing dance beats with orchestral sounds gives the music a whole new feel

Ellie Goulding, Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, Royal Albert Hall review - a mellow evening of strings and song

Replacing dance beats with orchestral sounds gives the music a whole new feel

Album: A Certain Ratio - It All Comes Down to This

Veteran Mancunians undergo a further re-assessment and reinvention

Album: A Certain Ratio - It All Comes Down to This

Veteran Mancunians undergo a further re-assessment and reinvention

Album: Maggie Rogers - Don't Forget Me

Rogers continues her knack for capturing natural moments, embracing a more live sound

Album: Maggie Rogers - Don't Forget Me

Rogers continues her knack for capturing natural moments, embracing a more live sound

theartsdesk at Tallinn Music Week - art-pop, accordions and a perfect techno hideaway

A revived sense of civilisation thanks to dazzlingly diverse programming

theartsdesk at Tallinn Music Week - art-pop, accordions and a perfect techno hideaway

A revived sense of civilisation thanks to dazzlingly diverse programming

Album: Lizz Wright - Shadow

Brilliant album from superlative vocalist

Album: Lizz Wright - Shadow

Brilliant album from superlative vocalist

Album: Shabaka - Perceive its Beauty, Acknowledge its Grace

A quiet and reflective breakthrough

Album: Shabaka - Perceive its Beauty, Acknowledge its Grace

A quiet and reflective breakthrough

Album: Nia Archives - Silence is Loud

Sweeping up generations' worth of influences into a giddy pop rush

Album: Nia Archives - Silence is Loud

Sweeping up generations' worth of influences into a giddy pop rush

Music Reissues Weekly: Patterns on the Window - The British Progressive Pop Sounds of 1974

A nebulous year in music resists easy definition

Music Reissues Weekly: Patterns on the Window - The British Progressive Pop Sounds of 1974

A nebulous year in music resists easy definition

Add comment