Twelfth Night/The Tempest, RSC, Roundhouse | reviews, news & interviews

Twelfth Night/The Tempest, RSC, Roundhouse

Twelfth Night/The Tempest, RSC, Roundhouse

The RSC's trio of shipwreck plays offer a watery journey through Shakespeare's career

The RSC’s Twelfth Night dumps its audience unceremoniously onto the shores of Ilyria in the thump and beat of waves. While Viola struggles from the (very deep and very real) water, asking “What country friends is this?”, we by contrast find ourselves in familiar territory. Like this season’s opener, A Comedy of Errors, both Twelfth Night and The Tempest take their birth in the water.

Jon Bausor’s designs are a miracle of twisted ingenuity, defeating perspective from every angle. A run-down resort hotel that could play host to Key Largo or Death in Paradise equally well spreads itself through 270 degrees, extending from the battered club armchairs and drinks-laden piano of the foyer to a bedroom with lazily rotating ceiling fan and bathtub.

Kevin McMonagle’s lugubrious lounge-crooner of a Feste is chief among the grotesques

Within this warped world Sir Toby (Nicholas Day) become a Hawaiian shirt-sporting lush, Sir Andrew (Bruce Mackinnon) a bumbling young toff and Malvolio (Jonathan Slinger) the manager, complete with golf buggy (“For the use of the management only”) and clipboard. It’s a conceit that generally holds up all the better for not being pushed too hard, though it rather seems to run out of steam where Orsino and Olivia are concerned.

Fortunately it’s a weight Day et al can more than bear. Kevin McMonagle’s lugubrious lounge-crooner of a Feste is chief among the grotesques, offering a profoundly sinister twinge in his encounter with the imprisoned Malvolio (Slinger, pictured right) on finest, most unsettling form, but getting the longest applause for turning the throwaway “You shall know more hereafter” into a sight-gag involving bare buttocks), while Mackinnon’s physical clowning and Day’s deviant way with phrasing all fill out the bleak comedy.

The undercooked emotions of the opening acts are exposed as raw in the dénouement, whose only dramatic kick comes in a final tableau that places all four lovers in one bed – a belated statement about the play’s sexual politics?

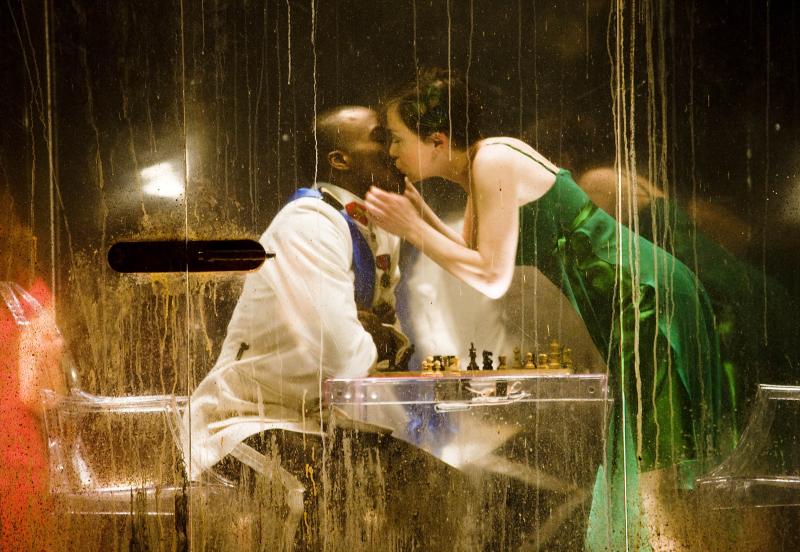

A chess set dominates the foreground of Bausor’s set for Twelfth Night – pointedly unused, except when cast violently to the floor in the final Act – surely a glance ahead to The Tempest and the triptych’s final panel, where passionate confusion at last gives way to reasoned order.

The physicality of Twelfth Night with its water-tank and slapstick here gives was to interiority. A Hokusai-inspired animation finds the sea at its most powerful, but also its most rarefied – the idea of a wave, rather than a wave itself. Key moments of action – the opening shipwreck dialogue, Ferdinand and Miranda’s game of chess – are banished to the glassy cage of Prospero’s “cell”, withdrawn from the audience. Only the spirits in their masque offer a generous spectacle, painting the washed-out greys of Bausor’s apocalyptic set briefly with colour and texture.

Farr’s Tempest is an altogether more delicate affair than the director’s Twelfth Night, with the tone set by Slinger’s Prospero. A sweating, dusty master in tattered suit and shirt, schooling Miranda (Taaffe) at a makeshift desk, there’s little dignity here. In its place we get a bitterness and fragility that from his first speech sets us up for an utterly sincere “But this rough magic I here abjure”. Ariel (Sandy Grierson) becomes his ghostly double, echoing Slinger’s broken pathos in an unusual scene of farewell, tending one last time – willingly – to his master, tenderly helping him with the buttons of his unfamiliar clothes.

Farr’s Tempest is an altogether more delicate affair than the director’s Twelfth Night, with the tone set by Slinger’s Prospero. A sweating, dusty master in tattered suit and shirt, schooling Miranda (Taaffe) at a makeshift desk, there’s little dignity here. In its place we get a bitterness and fragility that from his first speech sets us up for an utterly sincere “But this rough magic I here abjure”. Ariel (Sandy Grierson) becomes his ghostly double, echoing Slinger’s broken pathos in an unusual scene of farewell, tending one last time – willingly – to his master, tenderly helping him with the buttons of his unfamiliar clothes.

For all his restraint, Slinger is never less than emotionally clear, but his efforts are muddied by a rather confused Caliban from Amer Hlehel (pictured above). Grasping neither the moments of poetry, nor the ferocity of his hatred (and with diction often obscured), Hlehel is overpowered by the comedic double-act of Mackinnon (Stephano) and Felix Hayes’ Trinculo, who appropriate the character almost entirely for their subplot, leeching energy from his relationship with Prospero.

While linguistic traces of gender confusion do linger in the spoken text, a cross-cast Kirsty Bushell as Sebastian works dramatically very well in partnership with McGuinness, brittle once again as the foppish Antonio. The scheming pair offer a suitably sour contrast to Solomon Israel’s ingenuous Ferdinand.

For all the vigour and zest of Twelfth Night, Slinger’s Prospero proves the emotional core of this trilogy. Rich and strange indeed, the fallible magus and his surrender of power take us the final few steps from the streets of Ephesus to another world – a sea-change more of spirit than surroundings.

rating

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

more Theatre

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre review - brave, yes, but also misguided and bizarre

Sheridan Smith gives it her all against near-impossible odds

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre review - brave, yes, but also misguided and bizarre

Sheridan Smith gives it her all against near-impossible odds

The Divine Mrs S, Hampstead Theatre review - Rachael Stirling shines in hit-and-miss comedy

Awkward mix of knockabout laughs, heartfelt tribute and feminist messaging never quite settles

The Divine Mrs S, Hampstead Theatre review - Rachael Stirling shines in hit-and-miss comedy

Awkward mix of knockabout laughs, heartfelt tribute and feminist messaging never quite settles

Power of Sail, Menier Chocolate Factory review - alternately stiff and startling

Paul Grellong play delivers in its final passages

Power of Sail, Menier Chocolate Factory review - alternately stiff and startling

Paul Grellong play delivers in its final passages

Add comment