Shirley Baker, Photographers' Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Shirley Baker, Photographers' Gallery

Shirley Baker, Photographers' Gallery

A forgotten photographer of the northern slums is rediscovered

When a photographer is as little known as Shirley Baker, it is probably only natural that we scour her work for clues to the personality behind the camera. Certainly, Baker’s photographs of inner city Salford and Manchester, taken over a period of 20 years, seem to offer as full and intriguing a picture of Baker herself as of the disappearing communities she was committed to recording.

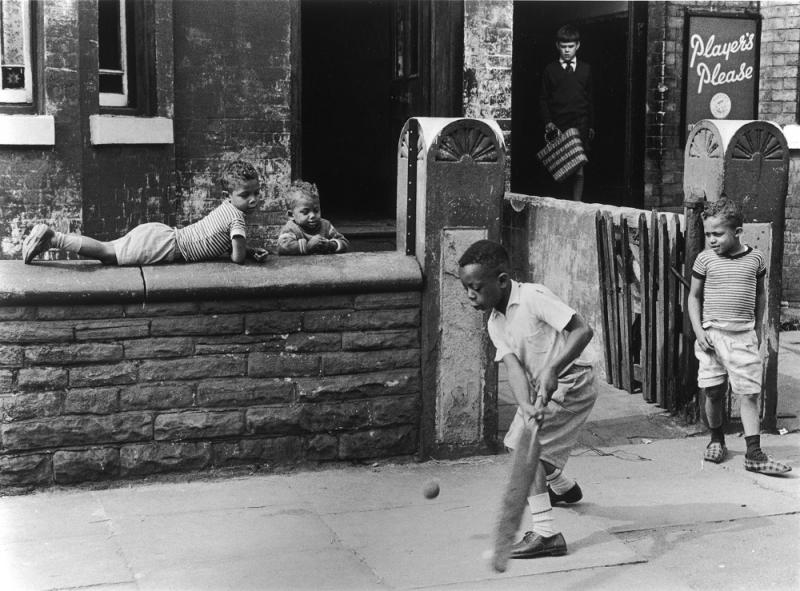

It is Baker's pictures of children that are the most telling: she was fascinated by what she perceived to be the "blissful innocence" enjoyed by inner city children, whom she pictures groping around inside a drain, playing in the open ruins of a part-demolished house or playing hopscotch and cricket in the street. Such freedom would be seen as neglect today, and since Baker was a middle-class woman married to a GP, the contrast with the restrictive upbringing of apparently more privileged children must have been striking.

The slums were a world apart from Baker's own genteel environs, and yet her pictures never romanticise what she sawShe certainly knew not only how to talk to children, but how to make them laugh. A picture from Manchester in 1962 shows three boys struggling to keep still and about to erupt into giggles, all gappy teeth and grins, but nevertheless relaxed and happy to be photographed. Part of Baker's secret lay in her choice of camera, a Rolleiflex which was perfect for the job. With the viewfinder on top, the camera had to be held at waist level, allowing a lower viewpoint ideally suited to shooting children, and leaving her face unobscured so that she was free to chat and make eye contact.

More fundamentally though, Baker’s readiness to use humour not only allowed her to form a bond with the people she photographed, but also steered her away from the common pitfalls of documentary photography. The slums were a world apart from Baker's own genteel environs, and yet her pictures never romanticise what she saw. She viewed it as her duty to record the destruction of great swathes of these northern cities, explaining: "I wanted to do something. But what could I do? I decided I would go out on the streets capturing this upheaval, photographing people I came across".

A picture taken during a brief and in her view unsuccessful experiment with colour gives a vivid impression of Baker’s playful wit. An old man feeding pigeons in the street has a little echo in the cat sat next to him, whose black patches look much like the old man’s hat, which in turn finds an unlikely echo in the outlines of the pigeons (pictured above: Hulme, May 1965).

A picture taken during a brief and in her view unsuccessful experiment with colour gives a vivid impression of Baker’s playful wit. An old man feeding pigeons in the street has a little echo in the cat sat next to him, whose black patches look much like the old man’s hat, which in turn finds an unlikely echo in the outlines of the pigeons (pictured above: Hulme, May 1965).

Clearly, she was a familiar if eccentric local face; in one picture a group of boys acknowledge her with a friendly wave, while elsewhere she is greeted with something more like patient resignation. For all that, she never went indoors, not because she wasn’t invited, but because to accept would have been an imposition. Bill Brandt, who, decades before had photographed similar scenes of working-class life, was notably untroubled by such niceties and his pictures often make uncomfortable viewing. Scenes such as his famous Northumbrian miner at his evening meal, 1937, suggest that for Brandt people presented a spectacle along the lines of animals in a zoo.

Her story highlights how many women of Baker’s generation were denied professional careersWhile Brandt had a highly successful career and remains one of the great names of 20th-century photography, Baker was almost unheard of in her own lifetime, although she was a frequent winner of competitions in magazines such as Amateur Photographer. In a feature from 1970 entitled “How to photograph children”, Baker’s prizewinning talents were rather predictably put down to her gender, the standfirst proclaiming: “You’d expect a woman photographer to be at home with such a subject.”

Baker was a reluctant amateur, whose ambitions to work as a press photographer were never realised. A generation too late for the news magazines that had championed photojournalism in the Forties and Fifties, Baker applied to The Guardian, one of the few remaining publications that ran picture-led stories. But according to Baker: “The Guardian ran a ‘closed shop’ for their photographers, open only to men.” The editor liked her work, and accepted the odd picture, but she would never join the staff.

There is a depressing familiarity about Baker’s story, which is ostensibly one of ambition thwarted by sexism and the burdens of domesticity. Photography boasts many examples of extraordinary women, like Lee Miller and Margaret Bourke-White who threw themselves into the male-dominated world of war reportage and produced some of the most enduring images of the Second World War. In many ways, such glittering success stories are misleading, and tend to suggest that women with sufficient talent and determination would eventually succeed. The truth is probably more closely aligned to Shirley Baker's experience, and her story highlights how many women of Baker’s generation were denied professional careers; in fact, even today many women will recognise some of the obstacles that she faced.

Nevertheless, even Baker herself acknowledged that her enforced amateur status ultimately benefited her work, giving her the freedom to pursue her own interests. Looking at her pictures now, time seems key to their success. Standing around, watching and waiting, revisiting the same places again and again, gave her a unique familiarity not just with the people, but also the places themselves. She was acutely aware of the physical environment her subjects inhabited and her sensitivity to its textures and contrasts, whether in puddles, bricks, chimney stacks, lace curtains, or the pieces of wood piled to make a bonfire, is essential to her command of black and white. (Pictured above: Manchester, 1968)

Nevertheless, even Baker herself acknowledged that her enforced amateur status ultimately benefited her work, giving her the freedom to pursue her own interests. Looking at her pictures now, time seems key to their success. Standing around, watching and waiting, revisiting the same places again and again, gave her a unique familiarity not just with the people, but also the places themselves. She was acutely aware of the physical environment her subjects inhabited and her sensitivity to its textures and contrasts, whether in puddles, bricks, chimney stacks, lace curtains, or the pieces of wood piled to make a bonfire, is essential to her command of black and white. (Pictured above: Manchester, 1968)

But the physical environment provided more than a textural palette to play with; her close-up pictures of graffiti seem curiously, even shockingly out of keeping with her time. Some of her best pictures use graffiti or advertising boards like a caption, providing a pithy counterpoint to an image. Much as Baker insisted that she never staged shots, these pictures self-evidently result from considerable thought, and she must have stood about waiting for the shot to come together, something that would have been far harder to achieve had she been a slave to deadlines.

Explore topics

Share this article

more Visual arts

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Issy Wood, Study for No, Lafayette Anticipations, Paris review - too close for comfort?

One of Britain's most captivating young artists makes a big splash in Paris

Issy Wood, Study for No, Lafayette Anticipations, Paris review - too close for comfort?

One of Britain's most captivating young artists makes a big splash in Paris

Add comment