DVD: The Czechoslovak New Wave - A Collection, Vol 2 | reviews, news & interviews

DVD: The Czechoslovak New Wave - A Collection, Vol. 2

DVD: The Czechoslovak New Wave - A Collection, Vol. 2

Three stylistically different films from one of the most remarkable cinema movements of the 20th century

Distributor Second Run’s second collection of the Czech New Wave (strictly speaking, Czechoslovak, although the three films included here are from the Czech side of the movement) reminds us what an astonishing five years or so preceded the Prague Spring of 1968. What a varied range of film-makers and filmic styles it encompassed, making any attempt to impose any external category – whether political or artistic – redundant.

The fate of the directors involved was as varied as the works they produced during that short-lived period of political thaw and formal experimentation. Many of those who remained in Czechoslovakia after the Soviet (Warsaw Pact) invasion saw their careers curtailed (relegation to television was a frequent fate), while others left the country and worked, with varying degrees of success, outside their homeland.

These tentative steps towards happiness never quite end up as hoped for

Miloš Forman is surely the foremost figure in the latter category. A Blonde in Love (Lásky jedné plavovlásky) from 1965 was his second feature, and the first to bring him international acclaim (including a Best Foreign Film Oscar nomination the following year). The 50th anniversary of its initial release confirms its position among the very top works of the movement: in fact, it surely ranks as one of the best films of the 1960s, period.

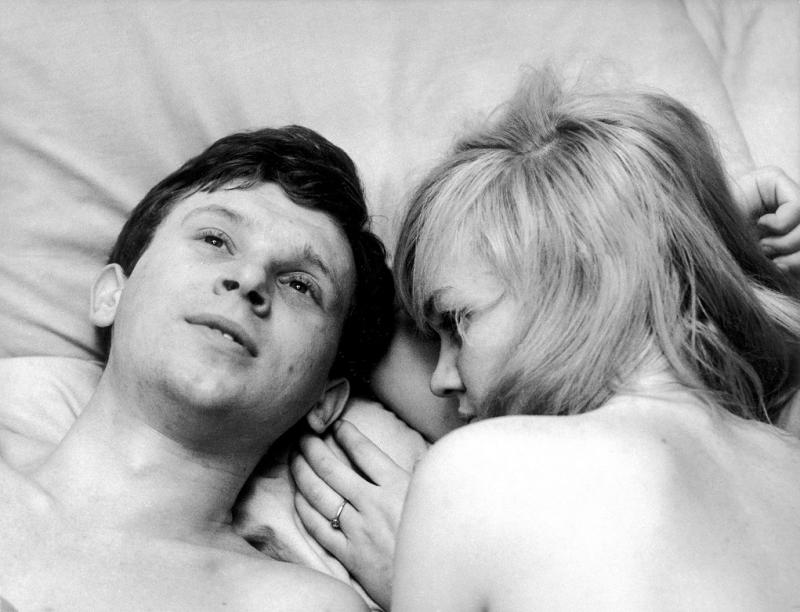

It’s intimate and funny at the same time, catching the fate of youthful hopes in a society which imposes pressures, direct or indirect, that contrive against their coming to fruition (no surprise that British director Ken Loach has repeatedly named it his favourite film). Life in a small town offers little for the hordes of young women working in its shoe factory, until the arrival of an army division brings hopes of greater social interaction. But Forman (and his co-writer and assistant director Ivan Passer) exquisitely capture the awkwardness of such developments; these tentative steps towards happiness never quite end up as hoped for, in scenes of comedy that are both agonising and delicious. (The central love scene between Andula and Mlida, pictured above, is both emotionally close and daring for its time).

Jan Němec’s 1966 The Party and the Guests (O slavnosti a hostech) is a more oblique film, notionally – though never quite directly – political. Němec wrote this quasi-parable with his wife (herself a remarkable costume-designer of the period) Ester Krumbachová, and cast many of the intelligentsia of his generation in supporting roles, a gesture that was lost on no-one. It’s the story of how a group of apparently carefree friends out in the country are accosted by a threatening crowd to be taken off to a mysterious birthday party on the banks of a lake, with each stage of their acquiescence becoming another step in their absorption into a group, “Party” mentality. At a little more than an hour, it’s a compressed study of the mentality of a society of control, mixed with a hint of Surrealism (we learn from film scholar Peter Hames’s filmed extra that Němec hadn’t apparently seen Buñuel, to whose work the film is much compared, when he made it), as well as elements of its local antecedent, Franz Kafka.

Jiří Menzel’s masterpiece may be Closely Observed Trains, which won the director the Best Foreign Film Oscar in the fateful year of 1968, but his Larks on a String (Skřivánci na niti) from the following year comes a close second. The ranks of films from the period to be banned after the Soviet invasion is a long and honourable one – The Party and the Guests was actually banned twice, the second time “for eternity” – and Larks remained virtually unseen in the year of its release (bootleg videos apparently circulated widely in the 1980s, however), before it went on to win the Golden Bear at the 1990 Berlinale.

Jiří Menzel’s masterpiece may be Closely Observed Trains, which won the director the Best Foreign Film Oscar in the fateful year of 1968, but his Larks on a String (Skřivánci na niti) from the following year comes a close second. The ranks of films from the period to be banned after the Soviet invasion is a long and honourable one – The Party and the Guests was actually banned twice, the second time “for eternity” – and Larks remained virtually unseen in the year of its release (bootleg videos apparently circulated widely in the 1980s, however), before it went on to win the Golden Bear at the 1990 Berlinale.

As with Trains, Menzel was collaborating with the great Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal, in this case from a collection of his stories about the fate of those found undesirable by the incoming 1948 Communist regime, who were sent off to hard labour or the mines (a moment of interaction between the new and old generations, pictured above). It’s in one such location, a monumental scrap yard, that the film’s motley collection of apparent undesirables live out their lives, with rich (often tragi-comic) interaction between the sexes across the borders of their confinement.

Larks comes with a 10-minute special feature, a 7 Questions for Menzel which the director filmed himself, giving background to his life and work within the context of his country’s history. His final utterance seems a rather jaundiced comment on the films of the present day (this was filmed in 2011): they're an escape from real life, Menzel complains, they lack compassion. Definitely not accusations that could be levelled at the work included in this release.

rating

Share this article

more Film

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

Blu-ray/DVD: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

Blu-ray/DVD: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

Back to Black review - rock biopic with a loving but soft touch

Marisa Abela evokes the genius of Amy Winehouse, with a few warts minimised

Back to Black review - rock biopic with a loving but soft touch

Marisa Abela evokes the genius of Amy Winehouse, with a few warts minimised

Civil War review - God help America

A horrifying State of the Union address from Alex Garland

Civil War review - God help America

A horrifying State of the Union address from Alex Garland

The Teachers' Lounge - teacher-pupil relationships under the microscope

Thoughtful, painful meditation on status, crime, and power

The Teachers' Lounge - teacher-pupil relationships under the microscope

Thoughtful, painful meditation on status, crime, and power

Blu-ray: Happy End (Šťastný konec)

Technically brilliant black comedy hasn't aged well

Blu-ray: Happy End (Šťastný konec)

Technically brilliant black comedy hasn't aged well

Evil Does Not Exist review - Ryusuke Hamaguchi's nuanced follow-up to 'Drive My Car'

A parable about the perils of eco-tourism with a violent twist

Evil Does Not Exist review - Ryusuke Hamaguchi's nuanced follow-up to 'Drive My Car'

A parable about the perils of eco-tourism with a violent twist

Io Capitano review - gripping odyssey from Senegal to Italy

Matteo Garrone's Oscar-nominated drama of two teenage boys pursuing their dream

Io Capitano review - gripping odyssey from Senegal to Italy

Matteo Garrone's Oscar-nominated drama of two teenage boys pursuing their dream

The Trouble with Jessica review - the London housing market wreaks havoc on a group of friends

Matt Winn directs a glossy cast in a black comedy that verges on farce

The Trouble with Jessica review - the London housing market wreaks havoc on a group of friends

Matt Winn directs a glossy cast in a black comedy that verges on farce

Add comment