Bon voyage, Jean Anouilh! | reviews, news & interviews

Bon voyage, Jean Anouilh!

Bon voyage, Jean Anouilh!

The author introduces 'Welcome Home, Captain Fox!', his new Donmar adaptation of Anouilh's 'Le voyageur sans baggage'

In the icy early hours of 1 February 1918 a bizarre figure was seen wandering aimlessly along the platform of a railway station in Lyon. A solider. Lost. When asked his name he answered, “Anthelme Mangin”. Other than that he had no memory of who he was, of where he had been, of where he was going, or of what had happened to him prior to arriving on that station platform on that frigid February night.

The story of Anthelme Mangin captivated France. For many he was the living embodiment of the unknown soldier buried beneath the Arc de Triomphe. A walking, talking memorial to the horrors of the First World War, and a symbol of hope to the families who desperately claimed him as their own.

Among those enthralled by Mangin’s story was the young playwright Jean Anouilh, who was searching for a subject for one of his early plays. To him there was something poignant and funny about the way in which Mangin was hawked around from family to family by psychiatrists in an attempt to discover his true identity, and in 1937 Anouilh’s comedy, Le Voyageur sans bagage, fictionalising one such meeting, opened in Paris to critical acclaim.

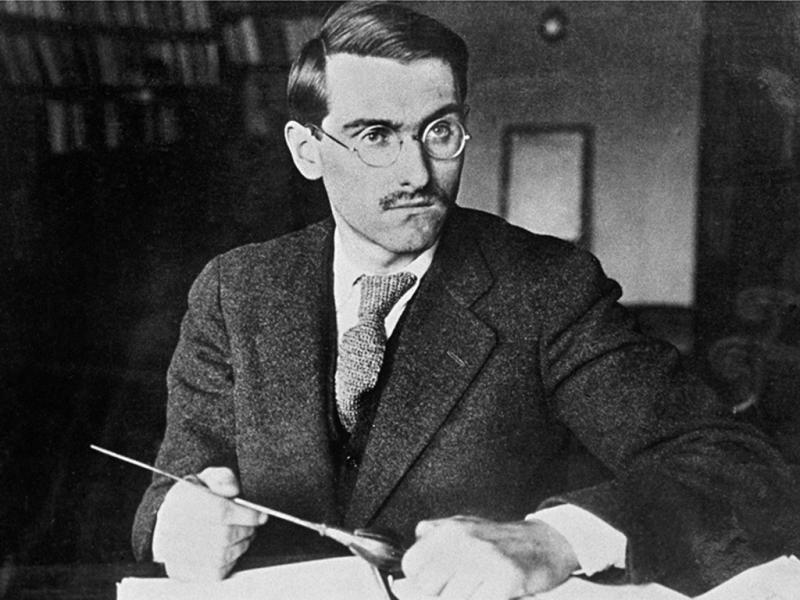

There was something enchanting about the idea to me as well. A copy of Anouilh’s play sat as a paperweight on my desk for a long while before a chance conversation with Donmar Warehouse artistic director Josie Rourke made me pick up the play and look at it again. Josie mentioned the long tradition in French literature of the unknown man, often a warrior, who walks out of a misty past and attempts to make life anew. A character like Dumas’s Martin Guerre, or Hugo’s Jean Valjean. (Pictured above: Barnaby Kay as George Fox in rehearsal)

There was something enchanting about the idea to me as well. A copy of Anouilh’s play sat as a paperweight on my desk for a long while before a chance conversation with Donmar Warehouse artistic director Josie Rourke made me pick up the play and look at it again. Josie mentioned the long tradition in French literature of the unknown man, often a warrior, who walks out of a misty past and attempts to make life anew. A character like Dumas’s Martin Guerre, or Hugo’s Jean Valjean. (Pictured above: Barnaby Kay as George Fox in rehearsal)

As we talked I began to wonder about other traditions similarly fascinated with an unknown man remaking himself. It spoke of a world where class and position couldn’t pin you down. A world in thrall to reinvention. A world in which your story was your currency. That world, that idea, was of course, America. American culture was littered with history-less men, remaking themselves with stories about who and what they were. Just think of Jay Gatsby!

There was something too about this idea that especially spoke to me of the innocent and credulous world of America in the 1950s. While Europe was struggling out from under years of war and conflict, America was glowing with affluence and optimism. Deliriously capitalistic, it was a world that was perfectly captured in the sumptuously filmed melodramas of Douglas Sirk and the glittering screwball comedies of Billy Wilder.

Not needing much of an excuse, I plonked myself on the sofa and began to binge on the classic films of that decade. And what a decade it was! Some Like It Hot, The Apartment, Written on the Wind, Imitation of Life, Invasion of the Body Snatchers. I got up off the sofa delirious. (Pictured below: Katherine Kingsley as Mrs Marcee Dupont-Dufort in rehearsal)

I began to think about the act of adaptation and why I liked it so much. To me, adaptation is always a conversation. A conversation with another author – across form, culture, language, time and space. I cock an ear, to listen both for what the author is saying, and often to what they’re not. There’s something about adapting that makes me feel accompanied. Less alone. Sometimes the conversation I’m having is pretty polite. Sometimes it’s more verbose. Boisterous even.

I began to think about the act of adaptation and why I liked it so much. To me, adaptation is always a conversation. A conversation with another author – across form, culture, language, time and space. I cock an ear, to listen both for what the author is saying, and often to what they’re not. There’s something about adapting that makes me feel accompanied. Less alone. Sometimes the conversation I’m having is pretty polite. Sometimes it’s more verbose. Boisterous even.

I wondered if the conversation I was having with Monsieur Anouilh might need to be a bit more raucous. I wondered if I shouldn’t invite a few more guests to the party. I wondered if by taking the broad dramatic arc of Anouilh’s original play, and reflecting it through a new set of circumstances provided by, say, Sirk and Wilder and their version of America in the 1950s, something new and delighting might not turn up.

So I set to work. I took Anouilh’s lost man, gave him a nice short haircut, bought him a smart Brooks Brothers suit, introduced him to the kind of Martini-soaked family that would have made even Freud’s eyes water, and plunged him in to the rarified world of a hot summers weekend in the Hamptons in the late 1950s.

Hopefully, the result – part me, part Anouilh, part Sirk, part Wilder – is a very human and forgiving story about a man with no memory found wandering along a railway station platform, desperate for happiness, whose future is only as bright as the story he chooses to tell about his past.

Explore topics

Share this article

more Theatre

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre review - brave, yes, but also misguided and bizarre

Sheridan Smith gives it her all against near-impossible odds

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre review - brave, yes, but also misguided and bizarre

Sheridan Smith gives it her all against near-impossible odds

The Divine Mrs S, Hampstead Theatre review - Rachael Stirling shines in hit-and-miss comedy

Awkward mix of knockabout laughs, heartfelt tribute and feminist messaging never quite settles

The Divine Mrs S, Hampstead Theatre review - Rachael Stirling shines in hit-and-miss comedy

Awkward mix of knockabout laughs, heartfelt tribute and feminist messaging never quite settles

Add comment