La clemenza di Tito, Glyndebourne review - fine musical manoeuvres in the dark | reviews, news & interviews

La clemenza di Tito, Glyndebourne review - fine musical manoeuvres in the dark

La clemenza di Tito, Glyndebourne review - fine musical manoeuvres in the dark

Meaningful one-to-ones and Mozartian excellence founder in the obscurity of this setting

So much light in the Glyndebourne production of Brett Dean's Hamlet; so much darkness in Mozart's La clemenza di Tito according to director Claus Guth.

The wild reedbeds of the two leading characters' childhood are still there against a pitch-black background; above, when the video of the past isn't playing – with a technical hitch through last night's Overture – two grim neo-classical rooms represent the Roman palace, often populated by that cliche of concept opera, men in black suits (played by both sexes of the ever-game and resonant Glyndebourne chorus and unnecessary extra actors). Christian Schmidt's designs don't really work, half messy naturalism, half metaphor (one we actually could have done with in the much worse Glyndebourne production of Mozart's La finta giardiniera, where the crumbling ballroom failed to capture the contrast between civilization and the wilds).

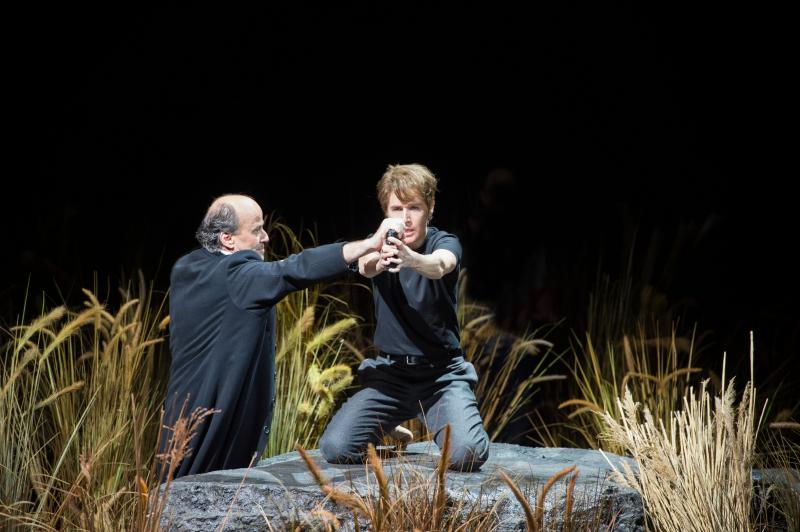

It's a pity, because much of what is acted and sung out against this is the best of personenregie, the director's art of getting the singers to engage humanly and meaningfully with each other, and has focus and fire (pictured above: the Emperor's beloved prospective consort Berenice is sent away for state reasons). What we see would be possible in just about any setting including the Roman (Glyndebourne's last and only previous production, by Nicholas Hytner, had pretty Pompeiian reds and blues framing a tepid drama). The revelatory clarity and flexible expression Glyndebourne Music Director Robin Ticciati draws from the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment are matched by nearly all the singing from superb stylists.

It's a pity, because much of what is acted and sung out against this is the best of personenregie, the director's art of getting the singers to engage humanly and meaningfully with each other, and has focus and fire (pictured above: the Emperor's beloved prospective consort Berenice is sent away for state reasons). What we see would be possible in just about any setting including the Roman (Glyndebourne's last and only previous production, by Nicholas Hytner, had pretty Pompeiian reds and blues framing a tepid drama). The revelatory clarity and flexible expression Glyndebourne Music Director Robin Ticciati draws from the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment are matched by nearly all the singing from superb stylists.

Yet even here there's a catch. The decent, ritual-trapped Emperor, Richard Croft – a superb replacement for Steve Davislim, who left owing to "differences" – looks twice the age of his best friend Sesto (wondrous Anna Stéphany an equally silvery replacement for Kate Lindsey, who found herself with child). Not only does it take longer to twig that they're the two boys of the video sequences, but the relationship seems more that of father Idomeneo and son Idamante in Mozart's earlier, more ambitious opera seria masterpiece.

Alice Coote's Vitellia (pictured below with Stéphany and Clive Bayley's Publio), full of colours and perceptive patches of interpretation, is also more of Tito's generation than that of the young people in the cast (the others are Michèle Losier as Sesto's friend Annio, a more likely candidate for the boy friend and making a huge impression in her fine Act Two aria, and the meltingly musical Joélle Harvey as Annio's beloved Servilia, at one brief point slated to be the Emperor's consort). Coote sometimes overshoots the mark, though not as gravely as in her recent concert performance of Handel's Ariodante, in which role my colleague Alexandra Coghlan admired her far more than I did. We need a bit of sexy seduction in the lovely upward chromatic figures to which Mozart sets the word "alletta" ("allures") in her first aria; the great final Rondo is played as a hit-and-miss mad scene with the house lights up (why?), its motivation not quite developing from what's gone before.

Stéphany, though, is a revelation – at least to anyone who didn't see her second-cast Octavian in the Royal Opera Der Rosenkavalier. Here, as there, she looks the handsome lead boy to perfection; and it's so exciting to hear a youthful mezzo voice flexible enough to do anything. Ticciati supports her to the hilt with space and the odd silence in her two tremendous set pieces (credits really due in the programme to the basset clarinet obbligato soloist, as for the basset horn in Vitellia's "Non più di fiori" - now, thanks to a commenter below, identifiable respectively as Katherine Spencer and Antony Pay).

Stéphany, though, is a revelation – at least to anyone who didn't see her second-cast Octavian in the Royal Opera Der Rosenkavalier. Here, as there, she looks the handsome lead boy to perfection; and it's so exciting to hear a youthful mezzo voice flexible enough to do anything. Ticciati supports her to the hilt with space and the odd silence in her two tremendous set pieces (credits really due in the programme to the basset clarinet obbligato soloist, as for the basset horn in Vitellia's "Non più di fiori" - now, thanks to a commenter below, identifiable respectively as Katherine Spencer and Antony Pay).

The conductor's "speaking" pauses, a feature of his work at Glyndebourne ever since the touring Jenůfa, are reflected in less successful ones during the recitative – the director's responsibility, I'm guessing – which hold up the drama rather than turning the screw as intended. They become maddening in Tito's anguish at whether to execute or pardon his treacherous best friend in Act Two; Richard Croft does his best to draw us into the emperor's head, but it doesn't quite work. The cumulative aria "Se all'impero," though, couldn't be finer; having started in Act One a bit under the note, Croft nails both the music and the expression in tandem with the OAE's flaming violin arpeggios. After all, this is a gift from the nub of Mozart's enlightened take on an old opera seria text, for all its toadying to the newly-crowned Emperor Leopold: "If I cannot assure the loyalty of my realms by love, I care not for a devotion born of fear." Not a common sentiment among today's demagogues.

That turning-point ought to herald a genuinely happy ending. But while Tito's liberation as the soaring magpie is partial cause for joy, we see him handing over power to the sinister manipulator Publio (Clive Bayley, suitably cold and lugubrious). No regie director ever allowed a happy ending if he or she could help it; so what started in the dark ends in the dark. All's definitely not well that ends well in this Clemency; and again that's a shame, because the performance of the music breathes sweetness and light.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

more Opera

Simon Boccanegra, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - thrilling, magnificent exploration

Verdi’s original version of the opera brought to exciting life

Simon Boccanegra, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - thrilling, magnificent exploration

Verdi’s original version of the opera brought to exciting life

Aci by the River, London Handel Festival, Trinity Buoy Wharf Lighthouse review - myths for the #MeToo age

Star singers shine in a Handel rarity

Aci by the River, London Handel Festival, Trinity Buoy Wharf Lighthouse review - myths for the #MeToo age

Star singers shine in a Handel rarity

Carmen, Royal Opera review - strong women, no sexual chemistry and little stage focus

Damiano Michieletto's new production of Bizet’s masterpiece is surprisingly invertebrate

Carmen, Royal Opera review - strong women, no sexual chemistry and little stage focus

Damiano Michieletto's new production of Bizet’s masterpiece is surprisingly invertebrate

La scala di seta, RNCM review - going heavy on the absinthe?

Rossini’s one-acter helps young performers find their talents to amuse

La scala di seta, RNCM review - going heavy on the absinthe?

Rossini’s one-acter helps young performers find their talents to amuse

Death In Venice, Welsh National Opera review - breathtaking Britten

Sublime Olivia Fuchs production of a great operatic swansong

Death In Venice, Welsh National Opera review - breathtaking Britten

Sublime Olivia Fuchs production of a great operatic swansong

Salome, Irish National Opera review - imaginatively charted journey to the abyss

Sinéad Campbell Wallace's corrupted princess stuns in Bruno Ravella's production

Salome, Irish National Opera review - imaginatively charted journey to the abyss

Sinéad Campbell Wallace's corrupted princess stuns in Bruno Ravella's production

Jenůfa, English National Opera review - searing new cast in precise revival

Jennifer Davis and Susan Bullock pull out all the stops in Janáček's moving masterpiece

Jenůfa, English National Opera review - searing new cast in precise revival

Jennifer Davis and Susan Bullock pull out all the stops in Janáček's moving masterpiece

theartsdesk in Strasbourg: crossing the frontiers

'Lohengrin' marks a remarkable singer's arrival on Planet Wagner

theartsdesk in Strasbourg: crossing the frontiers

'Lohengrin' marks a remarkable singer's arrival on Planet Wagner

Giant, Linbury Theatre review - a vision fully realised

Sarah Angliss serves a haunting meditation on the strange meeting of giant and surgeon

Giant, Linbury Theatre review - a vision fully realised

Sarah Angliss serves a haunting meditation on the strange meeting of giant and surgeon

Der fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera review - compellingly lucid with an austere visual beauty

Bryn Terfel's Dutchman is a subtly vampiric figure in this otherworldly interpretation

Der fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera review - compellingly lucid with an austere visual beauty

Bryn Terfel's Dutchman is a subtly vampiric figure in this otherworldly interpretation

The Magic Flute, English National Opera review - return of an enchanted evening

Simon McBurney's dark pantomime casts its spell again

The Magic Flute, English National Opera review - return of an enchanted evening

Simon McBurney's dark pantomime casts its spell again

Così fan tutte, Welsh National Opera review - relevance reduced to irrelevance

School for lovers not much help to the singers

Così fan tutte, Welsh National Opera review - relevance reduced to irrelevance

School for lovers not much help to the singers

Comments

The soloist in the clarinet

Thanks for enlightenment. She

Thanks for enlightenment. She's one of the two clarinettists listed among the orchestral personnel - Antony Pay being the other ('+ basset horn', which reminds me to get the two instruments exactly right) - but best not to have assumed.

Were they short of jackets?