Classical CDs Round-Up 11 | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs Round-Up 11

Classical CDs Round-Up 11

Rewired Debussy, Bach on the accordion, and a whole lot of horns

CD of the Month

Trio! Horn Trios by Brahms, Mozart and Duvernoy Sarah Willis, horn; Cordelia Höfer, piano; Kotowa Machida, violin (Musik Alexander)

Trio! Horn Trios by Brahms, Mozart and Duvernoy Sarah Willis, horn; Cordelia Höfer, piano; Kotowa Machida, violin (Musik Alexander)

Such a gentle, understated opening; a simple, questioning violin theme, answered by horn under soft piano chords. It's autumnal, soulful, and it begins the greatest chamber work for solo horn ever composed, Johannes Brahms’s op.40 Trio for horn, violin and piano.

Horn players love Brahms's idiomatic writing for the instrument. His lifelong preference was for the valveless waldhorn, where notes outside the harmonic series are obtained by closing the right hand into the horn's bell. The Trio sounds best when the horn soloist can play with a hint of dark warmth, and never too loudly or aggressively. Which Sarah Willis can do effortlessly here, in the best modern-instrument recording of the piece I’ve heard. She excels in the more introspective moments, especially in the glorious slow movement where Brahms mourns his recently deceased mother. Ultimately this is a redemptive, positive work, and the affirmation in the final 6/8 rondo feels totally deserved and inevitable, with Willis negotiating Brahms's tricky writing with exuberance and panache.

But it's not just about the horn; this is a trio, and the other parts are given equal weight; there's a wealth of detail I'd not previously noticed in the piano writing, played here by Cordelia Höfer – listen to the harrowing climax of the Adagio. The violinist Kotowa Machida, like Willis a member of the Berlin Philharmonic, is similarly impressive, with a lovely veiled timbre when she's playing in the lower register.

The couplings are enjoyable, even if not plumbing the same depths as the main work. Frédéric Duvernoy's trio is a fun display piece, whilst the Mozart is an arrangement of his sublime Horn Quintet. Fiendishly difficult, it sounds well in its new colours. Don't switch the cd off after the final Rondo, or you'll miss a sparkling encore, made famous in the 1950s by Dennis Brain.

I admit to being a horn anorak, and my attention was drawn to this issue by virtue of its being distributed by Alexander of Mainz, the legendary German brass instrument makers. Sarah Willis, the English-born, sole female brass player in her orchestra, plays an Alexander 103 full double. Players love and loathe this idiosyncratic horn in equal measure, but it's the default professional instrument in much of Europe. I used to own an elderly example, and two years ago I sold it, replacing it with something shiny and American. I've been kicking myself ever since.

Other Releases

Bach: Goldberg Variations Teodoro Anzellotti, accordion (Winter and Winter)

Bach: Goldberg Variations Teodoro Anzellotti, accordion (Winter and Winter)

Winter and Winter released jazz pianist Uri Caine’s eccentric take on Bach’s Goldberg Variations several years ago – a fantastic, off-the-wall recording which leaves one marvelling at Bach’s indestructibility. You can attack this piece in so many ways, and it will invariably survive the assault. An understated keyboard aria frames thirty variations, each based on a simple descending bass line. What’s impressive is the variety conjured from such slender means, and how staying in the same key need never become boring. There’s an amazing range of moods, climaxing with a haunting slow variation.

So here’s this masterpiece transcribed for, err, accordion. Does it work? It does – there’s a wheezy intimacy about the instrument which suits this piece well, and everything sounds so very human, so very alive. The aforementioned slow variation 25 is heavenly – Teodoro Anzellotti’s restraint and control are breathtaking, and the flourish opening Variation 16 Overture is dazzling. The accordion’s colours occasionally prompt more outré associations, with Spongebob Squarepants and Parisian holidays coming to mind more than once. But no matter – this is a supremely entertaining disc, played with virtuosity and good humour. Plus I’m a sucker for Winter and Winter’s deluxe presentation.

Watch Teodoro Anzellotti on YouTube:

Bach: Six Brandenburg Concertos, Harpsichord and Violin Concertos

Bach: Six Brandenburg Concertos, Harpsichord and Violin Concertos

Apollo’s Fire, Jeanette Sorrell (Avie)

The Cleveland-based period instrument band Apollo’s Fire recorded this set of the Brandenburg Concertos over ten years ago, and now they’re being reissued on Avie with extra couplings. These performances took a few listenings to make an impact; my favourite recent recordings being those on modern instruments by Chailly and the Gewandhaus Orchestra.

With period readings one expects a bit more zing and astringency – think of Allesandrini’s Concerto Italiano accounts, or Reinhard Goebel’s insanely fast and assertive performances. Apollo’s Fire, formed in 1992 by the harpischordist Jeanette Sorrell sound warmer and softer grained at first, but you soon begin to notice the immaculate articulation and affectionate phrasing; everything’s a little quieter and understated. I liked the harpsichord solo linking the two movements of no.3, leading into an exhilarating finale which never feels as if it’s about to derail. Solo winds are excellent, with some particularly lovely recorder playing . I did miss a more assertive trumpet in no.2; John Thiessen’s technique is flawless but there’s little sense of danger. Listen out for some outrageous horn whoops in no.1 – hardly authentic, but a moment where you sense the players having fun with Bach.

Sorrell’s couplings are her sparkling performances of the D minor and F minor harpsichord concertos, together with Elizabeth Wallfisch playing her own transcription of the D minor concerto for violin, arguing that some of the thematic material sounds more idiomatic on the violin. It works well, but I’m too used to hearing this work on a keyboard.

Metamorphosis: String quartets by Bartók, Kurtág and Ligeti Cuarteto Casals (Harmonia Mundi)

Metamorphosis: String quartets by Bartók, Kurtág and Ligeti Cuarteto Casals (Harmonia Mundi)

Béla Bartók’s pungent String Quartet no.4, completed in 1928, dominates this well-programmed disc. And it’s wonderfully rendered by the Cuarteto Casals, who capture just the right blend of aggressive modernism and folk-inspired lyricism. Dissonance levels are pretty high, but I defy anyone not to respond to the foot stamping finale, or marvel at how time freezes in the central slow movement. Bartók’s genius was for transforming, metamorphosing his material; Georgy Ligeti’s String Quartet no 1 of 1954 is subtitled Métamorphoses nocturnes and was clearly influenced by his older compatriot. Ligeti was able to study the scores of Bartók’s quartets, though performances were forbidden in cold-war Hungary. There’s a very Bartókian delight in the use of different string sonorities, whether glistening ponticello effects or glacial, static chords. In contrast to Bartók’s angrily upbeat close, Ligeti’s quartet magically fades into silence.

After which, György Kurtág’s 12 Microludes for String Quartet from 1978 come as a bit of a shock – tiny, enigmatic exhalations, some lasting as little as fifteen seconds. But they’re here played with focus and intense concentration, and it’s fascinating to observe how much emotion can be expressed in such spare, uncompromising musical gestures, even if the feelings conveyed to me weren’t particularly warm and fuzzy.

Jean-Luc Darbellay: A Portrait Various Artists (Claves)

Jean-Luc Darbellay: A Portrait Various Artists (Claves)

A two-disc set of recordings made over the past decade celebrating the music of Jean-Luc Darbellay, a Swiss composer born in 1946. The first CD opens with Oyama, a colourful orchestral work from 2000, named after a Japanese undersea volcano; the music is full of edgy, violent energy. There are two striking works for horn quartet: Azur, and a quattro, the latter almost a twenty-first century reworking of Schumann’s Konzertstűck. We get several much quieter chamber works, most impressive being the brief Chant d’adieux for violin and viola – a delicate display of unshowy minimalism.

Darbellay’s Requiem, commissioned in 2001, is scored for a huge orchestra and massed choral forces. At times the sheer extravagance dilutes the sentiment; those grand guignol organ chords in the Rex Tremendae nearly provoke giggles. But just as Darbellay goes over the top, he wins you back with his restraint, as in the subsequent Recordare and Lacrimosa. Technically it’s highly accomplished music, and you sense that it must be a joy to sing and play. The live recording vividly captures every extreme of register and dynamic.

Watch the Kroumata Percussion Ensemble rehearsing Darbellay’s ‘Shadows:

Claude Debussy: Preludes (arranged for orchestra by Colin Matthews) Hallé Orchestra, Sir Mark Elder (Hallé)

Claude Debussy: Preludes (arranged for orchestra by Colin Matthews) Hallé Orchestra, Sir Mark Elder (Hallé)

Debussy or Matthews? Even the booklet doesn’t quite seem to know who to give most credit to. I listened to this disc repeatedly after reviewing Ophélie Gaillard’s cello recital. There, Craig Leon’s orchestrations are unobtrusive and functional; here, composer Colin Matthews achieves feats of uncanny magic, giving Debussy’s piano originals idiomatic orchestral life with supernatural skill. It’s the restraint that impresses most – his treatment of La fille aux cheveux de lin jaw-dropping in its simplicity.

Elsewhere there’s so much to revel in – the swirling winds in Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest or the pointed habenera rhythms in La Puerta del Vino. Matthews is a composer, and unafraid to intervene and embellish Debussy’s originals when necessary - it’s fascinating to follow this recording with the piano score and try to see what’s been added. We also get Matthews’ own witty postlude to the set, Monsieur Croche (the pseudonym used by Debussy when writing as a music critic) – aptly, this begain with him writing his own Debussian piano prelude and orchestrating it. Most of these pieces have appeared previously, but this 2 disc set collects the full set of Preludes together. They were originally commissioned by Sir Mark Elder and the Hallé, and these performances are fantastically accomplished. Brilliant.

Haydn: Twelve London Symphonies Les Musiciens du Louvre, Marc Minkowski

Haydn: Twelve London Symphonies Les Musiciens du Louvre, Marc Minkowski

(Naïve)

More period-instrument orchestral playing, with this generously filled, well-annotated 4 disc set containing Haydn’s final twelve symphonies (nos. 93-104), composed in the early 1790s for Haydn’s successful visits to London. There’s a refreshing, disarming directness and wit in this music, coupled with a complete lack of sentimentality. Which is not to say that Haydn’s symphonies are light-hearted divertimenti – some of the jokes can be very funny, but they’re often tempered by Adagio introductions of solemn beauty. Marc Minkowski’s Haydn is quirksome but rarely irksome; revelling in the irregularly shaped melodic phrases and unexpected key changes.

Minkowski’s French orchestra recorded these urgent performances live in Vienna last year and there’s a thrilling immediacy about the sound – incisive, meaty period strings and winds with such distinctive timbres –note those gorgeous, tick-tocking bassoons in the Clock, which must have impressed Prokofiev. And the trumpet solo at the end of the Military’s slow movement sounds like a trial run for Mahler’s Fifth, following on from some gleefully over the top percussion. I laughed out loud several times – at the harpsichord solo near the close of no.98, and at the timpani thwacks which kick off the Drum Roll. I won’t give away what happens in the slow movement of this Surprise, but I’d advise you not to turn the volume up too loud. My cat fled the living room and hasn’t returned since.

Sinikka Langeland: Maria’s Song Sinnika Langeland, voice, kantele; Lars Anders Tomter, viola; Kåre Nordstoga, organ (ECM)

Sinikka Langeland: Maria’s Song Sinnika Langeland, voice, kantele; Lars Anders Tomter, viola; Kåre Nordstoga, organ (ECM)

A welcome blast of chilly Nordic air after too much Schreker and Debussy, Sinnika Langeland’s Maria’s Song tells the Virgin Mary’s story as taken from the Gospel of St Luke. To accompany the texts, she uses Norwegian folk songs, medieval ballads and instrumental music by Bach. The Bach extracts are glorious – movements from the first Cello Suite and the D minor Chaconne played by Lars Ander Tomter’s husky viola, and Kåre Nordstoga’s baroque organ recorded in the Nidaros Cathedral, Trondheim. Langeland’s clear, powerful a cappella voice made the hairs on my neck stand on end, but the most effective moments are where she uses Bach as her starting point – effortlessly superimposing the texts over the instrumental originals.

At certain points she plays the kantele, a plucked medieval instrument. It’s an extraordinary sound, lonely, bleak but consolatory. Sit down with a glass of iced water and listen to this disc in one go; it’s one of the most arresting things I have heard all year.

Watch Sinnika Langeland play the kantele:

Franz Schreker: Orchestral Music and operatic excerpts Various Artists (EMI)

Franz Schreker: Orchestral Music and operatic excerpts Various Artists (EMI)

David Nice mentioned the Austrian composer Franz Schreker (1878-1934) in a recent Prom review. A lesser composer? Certainly lesser-known, at least in the UK. I became aware of his music after watching an Opera North production of his opera Der Ferne Klang nearly 20 years ago. I’d rather listen to Schreker’s Chamber Symphony any day than sit through a bloated Strauss tone poem. Schreker gained fame as an operatic composer in the first decades of the twentieth century, second in reputation only to Strauss in the 1920s, until the rise of Nazism stalled his career.

EMI’s two disc compilation is a treat – this music is refined, lucid and accessible. Schreker’s gift lay in creating exquisite sonorities – sample the use of harmonium and celesta in the Chamber Symphony, or the veiled string writing in the Op.8 Intermezzo. We get two arias from Der Ferne Klang, sung by Fischer-Dieskau (with piano backing) and Thomas Hampson, as well as two weighty operatic preludes. It’s all really worth investigating, especially if you’ve ever responded to late Mahler or early Schoenberg. Plus we get Franz Schmidt’s quirky Variations on a Hussar’s Song and Ferruccio Busoni’s Two Studies for ‘Doktor Faust’, the first of which is one of the most strangely unsettling pieces I know.

Stravinsky: The Rake’s Progress Jerry Hadley, Dawn Upshaw, Samuel Ramey, Chœur et Orchestre de l’Opéra de Lyon, Kent Nagano (WCJ)

Stravinsky: The Rake’s Progress Jerry Hadley, Dawn Upshaw, Samuel Ramey, Chœur et Orchestre de l’Opéra de Lyon, Kent Nagano (WCJ)

Though I love Stravinsky’s own 1960s recording of the Rake, this is an excellent modern alternative. It’s an anachronistic work; a neoclassical ballad opera composed in the late 1940s, with a libretto supplied by WH Auden and Chester Kallman suggested by a sequence of Hogarth etchings. The Faustian plot is bleakly amusing, but there’s also a whiff of something sulphuric; a conducting acquaintance told me that he never wanted to direct the piece again and that his Nick Shadow suffered a near-breakdown after several performances. What starts out sounding like witty, cool-headed pastiche quickly develops into something much more gripping and moving.

Nagano’s 1996 account was derived from stage performances in Lyon. The speeds are swift but the playing is so pointed and well-articulated, with every glint in Stravinsky’s sparkling wind writing clearly audible. And the late Jerry Hadley was ideally suited to portraying Tom Rakewell’s naïve, self-centred optimism, well-matched with Dawn Upshaw’s sympathetic Anne Trulove. Best of all is Samuel Ramey’s Shadow, exuding seductive menace. Quake at the climatic graveyard scene, with its bitonal continuo writing, and weep as Rakewell is condemned to a future in Bedlam.

As with most budget price opera reissues, there’s no libretto, but you do get a detailed synopsis. The diction is incredibly clear, so it’s easy to follow the stage action.

- Buy The Rake’s Progress on Amazon

- Read Edward Seckerson's review of the Glyndebourne revival

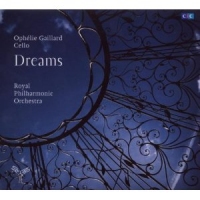

Ophélie Gaillard: Dreams Music for cello and orchestra; Ophélie Gaillard (cello), Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Timothy Redmond (Aparté)

Ophélie Gaillard: Dreams Music for cello and orchestra; Ophélie Gaillard (cello), Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Timothy Redmond (Aparté)

French cellist Ophélie Gaillard here gives us 14 well-known classical pieces, arranged and produced by one time Ramones producer Craig Leon. Refreshingly, all works well, Gaillard following a trend set by Casals and Piatigorsky in playing transcriptions of pieces not originally written for her instrument. She’s never indulgent, and there’s a refreshing urgency about the way she tackles warhorses like Rachmaninov’s Vocalise and Fauré’s Pavane. Craig Leon’s arrangements are unfussy but effective – the Song to the Moon from Dvořák’s Rusalka sounding well despite its provenance as a soprano aria, though the production throughout can sound a little synthetic and unnaturally balanced. This is much more rewarding than traditional crossover fare and left me wanting to hear Gaillard’s seductive tones in more traditional cello repertoire.

Watch Ophélie Gaillard play Bach:

{youtube}fyq4fOaX0Sc {/youtube}

Explore topics

Share this article

more Classical music

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Marwood, Power, Watkins, Hallé, Adès, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - sonic adventure and luxuriance

Premiere of a mesmeric piece from composer Oliver Leith

Marwood, Power, Watkins, Hallé, Adès, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - sonic adventure and luxuriance

Premiere of a mesmeric piece from composer Oliver Leith

Elmore String Quartet, Kings Place review - impressive playing from an emerging group

A new work holds its own alongside acknowledged masterpieces

Elmore String Quartet, Kings Place review - impressive playing from an emerging group

A new work holds its own alongside acknowledged masterpieces

Gilliver, LSO, Roth, Barbican review - the future is bright

Vivid engagement in fresh works by young British composers, and an orchestra on form

Gilliver, LSO, Roth, Barbican review - the future is bright

Vivid engagement in fresh works by young British composers, and an orchestra on form

Josefowicz, LPO, Järvi, RFH review - friendly monsters

Mighty but accessible Bruckner from a peerless interpreter

Josefowicz, LPO, Järvi, RFH review - friendly monsters

Mighty but accessible Bruckner from a peerless interpreter

Cargill, Kantos Chamber Choir, Manchester Camerata, Menezes, Stoller Hall, Manchester review - imagination and star quality

Choral-orchestral collaboration is set for great things

Cargill, Kantos Chamber Choir, Manchester Camerata, Menezes, Stoller Hall, Manchester review - imagination and star quality

Choral-orchestral collaboration is set for great things

Add comment