Cameraman: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff | reviews, news & interviews

Cameraman: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff

Cameraman: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff

A magic hour or two with the eyes of Hitchcock, Huston and Powell

The last time Jack Cardiff went to Cannes, nobody recognised him; wearing his trademark trilby, he'd tell curious autograph hunters he used to be a stand-in for Frank Sinatra. In fact Cardiff's claim to fame was somewhat greater: his was the eye behind some of the most achingly beautiful images in all of cinema. Handsome, charismatic and sharp as a tack, with a bottomless fund of funny and revealing anecdotes, he's also a dream subject for a documentarian. Naturally no television company was prepared to fund a film about him.

Consequently Cameraman The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff took its director, Craig McCall, 13 years to make, but it was finally unveiled at a premiere screening at the BFI Southbank last night, attended by Cardiff's family and introduced by Martin Scorsese, probably Cardiff's Number One Fan, and Sanjeev Bhaskar, a former collaborator and personal friend. And the result has been well worth waiting for. The only regret is that Cardiff died in April last year, aged 94, before the film was completed, though not before McCall captured his wit and wisdom in numerous interviews.

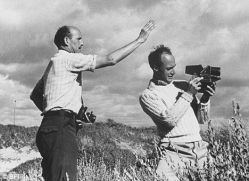

His career spanned the cinema's first century. Born into a showbusiness family in 1914, he appeared on screen at the age of four, and continued to work until 2007. In between he pioneered the then-new Technicolor process with directors including Alfred Hitchcock in Under Capricorn, John Huston in The African Queen and the four films he made with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Matter of Life and Death, Black Narcissus (memorably described by Bhaskar as about "a bunch of nuns in the Himalayas discovering that India makes you horny") and The Red Shoes. (Above: Cardiff, right, with Powell).

His career spanned the cinema's first century. Born into a showbusiness family in 1914, he appeared on screen at the age of four, and continued to work until 2007. In between he pioneered the then-new Technicolor process with directors including Alfred Hitchcock in Under Capricorn, John Huston in The African Queen and the four films he made with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Matter of Life and Death, Black Narcissus (memorably described by Bhaskar as about "a bunch of nuns in the Himalayas discovering that India makes you horny") and The Red Shoes. (Above: Cardiff, right, with Powell).

Cardiff photographed some of the most beautiful women in the world, both in movies and in a small but select suite of still portraits, including Ava Gardner (who warned him to light her differently while she was having her period), Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida, Ingrid Bergman, Deborah Kerr, Marlene Dietrich, Marilyn Monroe, Julie Christie and Audrey Hepburn. (Below: Cardiff's portrait of Monroe, with whom he worked on The Prince and the Showgirl). Among the roll-call of male stars are Humphrey Bogart, Fred Astaire, Kirk Douglas, Christopher Walken, Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Laurence Olivier.

Many of the stories Cardiff tells in Cameraman are familiar from his marvellous autobiography, Magic Hour, and the parade of celebrity interviewees, including Charlton Heston, Lauren Bacall and John Mills, often seem wheeled on for their star power rather than their insights (though there's a short, touching quote from an ailing Kirk Douglas). The film also features great swathes of Scorsese, whose enthusiasm is infectious and undisputed (asked if he has seen Sons and Lovers, Cardiff's most acclaimed film as a director, Scorsese ripostes, unanswerably, "Oh yes. I have my own print"). However, his observations - "It's about expressing colour" - are on the waffly and woolly side. The most eloquent moment comes when McCall drops in a split screen sequence juxtaposing Moira Shearer dancing in The Red Shoes with Robert De Niro boxing in Raging Bull, a film which Scorsese admits was heavily influenced by Cardiff's experimental camerawork. The two sequences mirror each other almost shot for shot.

Many of the stories Cardiff tells in Cameraman are familiar from his marvellous autobiography, Magic Hour, and the parade of celebrity interviewees, including Charlton Heston, Lauren Bacall and John Mills, often seem wheeled on for their star power rather than their insights (though there's a short, touching quote from an ailing Kirk Douglas). The film also features great swathes of Scorsese, whose enthusiasm is infectious and undisputed (asked if he has seen Sons and Lovers, Cardiff's most acclaimed film as a director, Scorsese ripostes, unanswerably, "Oh yes. I have my own print"). However, his observations - "It's about expressing colour" - are on the waffly and woolly side. The most eloquent moment comes when McCall drops in a split screen sequence juxtaposing Moira Shearer dancing in The Red Shoes with Robert De Niro boxing in Raging Bull, a film which Scorsese admits was heavily influenced by Cardiff's experimental camerawork. The two sequences mirror each other almost shot for shot.

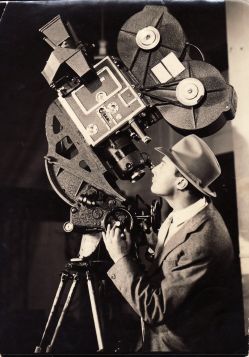

There are other excellent reasons for seeing Cameraman. Cardiff lived through a period when the possibilities of film technology were still being discovered (Below: the young Cardiff with an enormous early Technicolor camera). Many of his most memorable effects were achieved, not in post-production, but in-camera, through experiment, ingenuity and sheer imagination, and the generous, well-chosen clips amount to a masterclass in camera wizardry. Some (though sadly not all) of these films have been restored, allowing Cardiff's work for Powell and Pressburger in particular to dazzle in its full Technicolor glory and making you want to watch them all over again: a small part-retrospective plays at the BFI Southbank all month. A freshly restored version of The African Queen will be premiered next week in Cannes, where Cameraman will also receive a special screening. As yet no British television company has acquired it.

Sitting next to Cardiff's widow, Nicki, and surrounded by his family, I fully expected this film, and the evening, to be a sentimental nostalgia-fest, a wallow in regret for a lost loved one and the cinema's long-gone heyday. That it was not (Nicki was repeatedly to be heard loudly whooping her appreciation) was largely down to Cardiff's dynamic and forward-looking personality. As the British film industry declined, he got to work on the likes of Death on the Nile, Michael Winner's remake of The Wicked Lady, Conan the Destroyer and Rambo: First Blood Part II. Most might see those movies as a bit of a comedown, but Cardiff has always spoken of them with as much enthusiasm as the authentic masterpieces he shot: at the end of Cameraman, far from bemoaning that films have gone to the dogs, he praises the excellent standards of modern cinematography. "I had a lot of fun on Rambo," he also says, beaming, and, judging by his "home movies" - playing on a loop in the BFI cinema lobby - he was a cool guy to be around on a film set.

Sitting next to Cardiff's widow, Nicki, and surrounded by his family, I fully expected this film, and the evening, to be a sentimental nostalgia-fest, a wallow in regret for a lost loved one and the cinema's long-gone heyday. That it was not (Nicki was repeatedly to be heard loudly whooping her appreciation) was largely down to Cardiff's dynamic and forward-looking personality. As the British film industry declined, he got to work on the likes of Death on the Nile, Michael Winner's remake of The Wicked Lady, Conan the Destroyer and Rambo: First Blood Part II. Most might see those movies as a bit of a comedown, but Cardiff has always spoken of them with as much enthusiasm as the authentic masterpieces he shot: at the end of Cameraman, far from bemoaning that films have gone to the dogs, he praises the excellent standards of modern cinematography. "I had a lot of fun on Rambo," he also says, beaming, and, judging by his "home movies" - playing on a loop in the BFI cinema lobby - he was a cool guy to be around on a film set.

I experienced something of this when I met Cardiff in 1998. He was working with Bhaskar on The Dance of Shiva, an ultra low-budget student short film which was still awaiting completion funding at the time; the veteran production designer John Box and sound man John Mitchell were also there and all three men were clearly pleased as punch to be back in harness. I marvelled as Cardiff, then 84, heaved spotlights around and nipped up ladders to adjust them, before being comprehensively charmed by him over lunch. "I've been carrying the torch long enough," he said at the time. "Whatever you know, don't waste it, pass it on." Cameraman plays its own small part in helping to preserve his precious legacy.

Watch the sublimely romantic opening sequence of A Matter of Life and Death

Share this article

more Film

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

DVD/Blu-Ray: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

DVD/Blu-Ray: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

Back to Black review - rock biopic with a loving but soft touch

Marisa Abela evokes the genius of Amy Winehouse, with a few warts minimised

Back to Black review - rock biopic with a loving but soft touch

Marisa Abela evokes the genius of Amy Winehouse, with a few warts minimised

Civil War review - God help America

A horrifying State of the Union address from Alex Garland

Civil War review - God help America

A horrifying State of the Union address from Alex Garland

The Teachers' Lounge - teacher-pupil relationships under the microscope

Thoughtful, painful meditation on status, crime, and power

The Teachers' Lounge - teacher-pupil relationships under the microscope

Thoughtful, painful meditation on status, crime, and power

Blu-ray: Happy End (Šťastný konec)

Technically brilliant black comedy hasn't aged well

Blu-ray: Happy End (Šťastný konec)

Technically brilliant black comedy hasn't aged well

Evil Does Not Exist review - Ryusuke Hamaguchi's nuanced follow-up to 'Drive My Car'

A parable about the perils of eco-tourism with a violent twist

Evil Does Not Exist review - Ryusuke Hamaguchi's nuanced follow-up to 'Drive My Car'

A parable about the perils of eco-tourism with a violent twist

Io Capitano review - gripping odyssey from Senegal to Italy

Matteo Garrone's Oscar-nominated drama of two teenage boys pursuing their dream

Io Capitano review - gripping odyssey from Senegal to Italy

Matteo Garrone's Oscar-nominated drama of two teenage boys pursuing their dream

Add comment