theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Simon Callow | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Simon Callow

theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Simon Callow

The actor talks sex, Shakespeare and game-playing with Stephen Fry

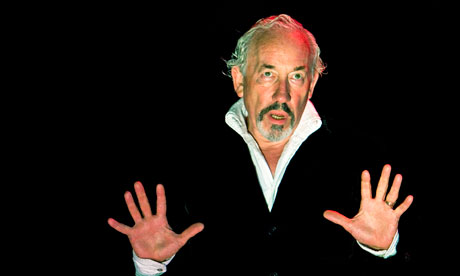

Simon Callow is on the phone when I arrive at his five-star digs, booming his apparently considerable misgivings vis-a-vis appearing in some reality TV exercise in which he will be asked to tutor disadvantaged kids in the mysterious arts of Shakespeare. “They keep saying it will be great”, he rumbles, “but it will only be great if it’s great.” And Amen to that.

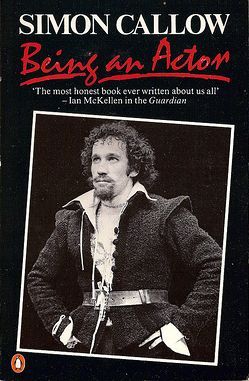

All voice, gesture and bustle, Callow (b 1949) couldn’t really be anything other than a certain kind of actor. Indeed, if you could bottle the quite extraordinary way in which he wraps lips, tongue and molars around the phrase “post hoc” you could bathe in it. With his neat, economical beard and fluffed-up white hair, at 61 he looks every inch the venerable thesp. So much so, in fact, that it’s easy to forget he’s actually an old-fashioned polymath who has directed films, plays and opera, as well as writing screenplays and weighty biographies of Oscar Wilde, Orson Welles (on whom he's two-thirds of the way into a trilogy, with the final instalment under construction) and Charles Laughton. His memoir-cum-manual Being an Actor (1984) is rightly lauded as a classic of its kind, and he has just published another autobiographical work called My Life in Pieces.

Yet it is clearly the art of acting that consumes him. Born in Streatham, south London, Callow was the product of a father who swiftly abandoned his family to cut loose in Africa, and a mother whom he describes as “peculiar and erratic and wrong-headed in many, many ways”. In acting he found both a refuge and a source of eternal fascination, and ever since has rarely stopped examining it from every available angle.  One of the first actors to publicly come out as gay, in 1984, Callow has connected with popular culture primarily due to his appearances – often small, always memorable – in films like Amadeus, where he portrayed Emanuel Schikaneder (pictured) having already played Mozart in Peter Hall's original stage version; as Tilney in Shakespeare in Love; and - perhaps his best-known role - as the gregarious Gareth in Four Weddings and a Funeral. He pops up on TV from time to time, in everything from Rome to Doctor Who, but he’s still most at home on the stage. In 2009 he played Pozzo in Sean Matthias’s production of Waiting for Godot at the Theatre Royal Haymarket, alongside Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen. Most recently, he took Jonathan Bate’s new one-man show, Shakespeare: The Man from Stratford, to Edinburgh and has only just finished touring it around the country.

One of the first actors to publicly come out as gay, in 1984, Callow has connected with popular culture primarily due to his appearances – often small, always memorable – in films like Amadeus, where he portrayed Emanuel Schikaneder (pictured) having already played Mozart in Peter Hall's original stage version; as Tilney in Shakespeare in Love; and - perhaps his best-known role - as the gregarious Gareth in Four Weddings and a Funeral. He pops up on TV from time to time, in everything from Rome to Doctor Who, but he’s still most at home on the stage. In 2009 he played Pozzo in Sean Matthias’s production of Waiting for Godot at the Theatre Royal Haymarket, alongside Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen. Most recently, he took Jonathan Bate’s new one-man show, Shakespeare: The Man from Stratford, to Edinburgh and has only just finished touring it around the country.

In conversation, everything about him hints at a restless, perhaps rather impatient energy. He doesn't really do understated, but we already knew that. As he switches roles, one minute declaiming chunks of Henry V, the next undertaking an uncannily accurate impersonation of a dour Edinburgh cabbie, his shirt stretches increasingly precariously across a drum-like torso. I spend an hour waiting for the buttons to pop.

GRAEME THOMSON: In My Life in Pieces you quote John Gielgud’s mother talking about her son. I’m paraphrasing, but she said something like: “When he wasn’t acting, talking about the theatre, or at the theatre, he wasn’t living." The same seems almost to apply to you as a young man. You seemed to truly need acting and immersed yourself in it. It seemed to bring you alive.

SIMON CALLOW: When I discovered acting it just became an obsession, a sort of brave new world. As a boy I was very widely read across the disciplines: world literature, philosophy, natural sciences. I knew a huge amount about music, and still do, I was interested in political theory and religions of all kinds. I was an omnivore but I was always basically self-educated. I didn’t go to good schools and the teaching wasn’t good at all, with one or two exceptions, so I found it all out for myself. I was tottering around never quite knowing what to do with all this stuff.

My idea of acting and actors is that it’s like a zoo where you see these extraordinary animals

Did you specialise?

I’d read everything Oscar Wilde had ever written and everything in print that had been written about him. I’d also read everything Christopher Isherwood had ever written, oddly enough, because I enjoyed his style so much. I was fascinated by his prose. I later sent him Being an Actor out of gratitude, and after he’d died I discovered from [the painter and Isherwood’s long-term partner] Don Bachardy that Isherwood was reading it for the second time when he was dying. Fucking hell! The words “for the second time” are particularly heart-warming for any writer, I’ve since discovered.

Did you believe that accumulating knowledge would help somehow to stitch you together as a person?

I was certainly looking for an answer of how to be, how to live. I discovered that the theatre, whether farce or tragedy, is always posing that question on some universal level: how to live? Personally, it was an answer to how I could live, because it meant I could apply myself to the job of being an actor, which meant I could create structures for myself within my life, have a skill – which I conspicuously lacked until that point – and become knowledgeable about something from the inside, which I certainly wasn’t. Acting finally became something that I’m an expert on.

You’ve been touring a highly demanding one-man show about Shakespeare. Does acting present the same challenges and bring the same pleasures as it did when you started, or do those things change with age and experience?

It has changed, because whenever you do anything a lot and find out more about it, your standards rise, you begin to realise what it could be, and you become much more ambitious for yourself. In the beginning, for me acting was mostly about adrenalin and the release into being other characters. That was it. The acting school I went to was a very rigorous one and we had a very good technique of working on our roles, but I never knew much about my physical and vocal technique, the way I handled myself. I just threw everything at it, that was my policy. As you get older you have less energy, not the same kind of adrenalin, and you begin to see, “Ah, yes, if I really work on it in this way I can achieve so much more and it will be so much more interesting for me and the audience.” The concomitant of that, of course, is that you have to work much harder and you never stop working. I know that no performance I’ve ever given has satisfied me. I always have the possibility the next day that I might get it right that time, but I never do.

You seem endlessly fascinated by acting – analysing it, writing about it, chipping away at it....

You seem endlessly fascinated by acting – analysing it, writing about it, chipping away at it....

It does fascinate me, but I don’t think I’m an analytical actor at all. The analysis is all post hoc, but I’m constantly astonished by the things that sometimes happen to one playing a part. Playing Pozzo last year in Waiting for Godot was just an extraordinary experience, not at all like I’d expected.

In what way?

Like all the greatest things it was both infinitely more simple and more complex than you think. I thought it would be fairly straightforward. It was one of those parts where people say, “Oh, you were born to play it,” and they are always the ones you can never play at all. I had no idea. With Beckett, as with Shakespeare, the text is the absolute and total royal road to success. Just look at what is said. That’s what Beckett himself constantly said. Actors would endlessly lament, “Sam, what does it mean?” “But Billie, what does it say?” Just. Read. It.

The more I looked at the text of Godot I realised that Pozzo is actually having a nervous breakdown. He keeps crying, there’s this massive sense of guilt about what he’s done to Lucky and their relationship before. So... how do you achieve that, then? I realised it’s about Empire. The first image is these two tramps arguing the toss, and then on comes a man with another man on the end of a rope, screaming commands at him. I thought, “It’s human history,” for what else is human history but one set of people dominating another? Then the play begins to open up. I’m not adding anything, it’s just what you see. I’m told when they first performed Godot in Africa, all black cast, the sight of a black man holding another black man on the end of a rope caused a commotion in the audience.

What did you learn about Shakespeare from this show?

It’s surprising all the time. For example, in the show I open the second half with the Henry V speech: “Once more unto the breach, dear friends...” I think that we all have, somewhere in our genes, a memory of Laurence Olivier doing that, and how utterly thrilling it is, taking it from a very rich, even tone until he’s flinging trumpets and percussion at it up in the top register. But it seems to me that he didn’t play what was written at all: “Then imitate the action of the tiger: Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood ... Now set the teeth and stretch the nostril wide; Hold hard the breath.” It’s an acting lesson! I didn’t know that from Olivier, did you? And Shakespeare was the first writer to perform the trick that Anton Chekhov perfected, of making people who are apparently quite ordinary, somehow making them translucent and emblematic of the whole human situation, but without stretching the parameters of the characters. Most great writers are surprising all the time – that’s what’s remarkable about them. How they achieve that is beyond us, but it’s just... surprising. That’s why acting is endlessly stimulating for me when you have truly great work. And at the moment I’m disinclined to do anything other than really great work, because what’s the point? Time is short.

You seem to work constantly. Do you worry about your work/life balance and is it possible to determine where one ends and the other begins?

I’m a bit compulsive about work. I have a tremendously wide circle of friends who I’m immensely connected to and love and see often, but I’ve never been one of those people who is able to think of life as divided between work and play. I’m not very good at playing, full stop. I have dogs who I love deeply, but I’m not very good at playing with them. They’re boxers and they’d like it if I could play better. I play with them a little bit and then I think, “Right, now I can stop playing,” but people who really know how to play never stop playing.

They never think, “Phew, now I’ve done the playing...”

Exactly. But then again my work is my play, and plays are my work. That’s the territory where I can relax. I was never any good at playing games - sport, or chess, or draughts, or cards, any of those things. I’m hopeless at it. I don’t like it. I was once corralled by Stephen Fry into attending the launch for this game Perudo. Stephen of course is terrific at all that, he loves it, but I was rather reluctant. I remember sitting at a table and I couldn’t get excited about it at all, and eventually I said, “Stephen forgive me, I am deeply unhappy doing this and I’m going to go.” I don’t think he understands even now why I had to do that, but I just couldn’t bear it. I hate competitive games very much as well, because I always feel I’m bound to lose. I realised in my life that, wherever I can, I’ve put myself in positions where I’m not actually in a competition, I’m just up against myself or some absolute critical criterion. What I’m doing at the moment falls into that category.

You’re drawn again and again in your work to the great characters and great wits: Welles, Wilde, Shakespeare. Do we by comparison live in a witless, characterless age?

You’re drawn again and again in your work to the great characters and great wits: Welles, Wilde, Shakespeare. Do we by comparison live in a witless, characterless age?

It’s true my heroes tend to be dead. I suppose there’s an aspect of me that’s drawn to people of scale and size and breadth and generosity. It relaxes one in a way, they’re on such a grand scale you can just be swept up in it. My maternal grandmother was a bit like that. She was sort of a universe in herself and I loved her dearly, dearly, dearly; so dearly that I eventually had to separate myself from her and pull myself out of her life for a few years, because her orbit was too compelling. I had to find myself and my independence from her.

One of the problems I have in the theatre now is that nobody really wants to function on that scale. The whole thing about acting was that actors were “larger than life”, and now they’re supposed to be life-sized – in fact some of them are smaller than life. The great ideal is to be recognisably ordinary, but my idea of acting and actors is that it’s like a zoo where you see these extraordinary animals. Sometimes you say, “Gosh, yes, that looks exactly like Uncle Fred,” or “I’ve felt the way that lion is feeling at the moment,” but you don’t feel you’re looking in a mirror. I’ve never thought that’s the purpose of art, which is why I’ve been so drawn to Dickens, because he works on such a massive canvas and creates characters who are like universes to themselves. Shakespeare does it, too. Falstaff and the nurse in Romeo and Juliet are like that, and Mistress Quickly. There’s an endlessness to them, they race along under their own impetus, and that fascinates me.

Tell me about your theory that homosexuals are actually very attractive to the great British public.

Ha! Yes, I came to the conclusion, having been brought up to believe that homosexuals were regarded as absolute pariahs, that in fact the idea of homosexuality was perhaps repulsive to the British public, but the reality of homosexuals, the actual people themselves, we the gay people, were not at all. The whole campness, floridity and vivacity, and maybe the emotionalism, of gay people is actually highly attractive to the British. After Gielgud was arrested in 1953 for cottaging, he’d gone to open the play he was appearing in in Liverpool – having been advised strongly by Olivier not to do it - and he came on stage expecting to be barracked, and instead got cheers and a huge, warm round of applause. They admired his courage, but also they were glad to see him. That’s a very powerful little moment in social history. The people who try to control what we think – the tabloid press, the church – completely underestimate human beings and their capacity for imagination. It turns out, on the whole, nobody gives a damn, except a hardcore of primitive people who hate the idea of anyone being different from them.

Where do these "primitives" find their expression? In other words, where do you meet that kind of homophobic resistance in your own life?

I don’t, is the truth of the matter. Well, not very much. You’re aware that people of a certain generation are a little nervous around the whole territory, but I think the way gay people handled themselves - which was, on the whole, admirable - around AIDS had a tremendous psychological effect. Taking responsibility for themselves and saying, “I couldn’t give a fuck any more whether you approve of me or not. My best friend is dying, I might be dying, fuck off! If you want to help, that’s great, if not just leave me alone.” The debate of coming out or not coming out has been re-opened by people like Rupert Everett saying, “If only I hadn’t come out I’d be a major film star now,” and Miriam Margolyes saying, “If only I hadn’t come out my mother would have died a happy woman.” Both of which are debateable in themselves, but sometimes you have to say that for the greater good transparency is the only way we can live. We cannot live on terms dictated to us by somebody else. If you don’t like it, too bad.

How did being gay impact on your childhood?

I was quite honest about my sexuality at school. Unfortunately I didn’t have any affairs - how I wish I had - but I was very honest about being attracted to certain boys, and there was no problem from them about it at all. Later [in 1975], when I was doing Passing By for Gay Sweatshop theatre company, I thought I should make the big announcement to my mother, because I knew the play would be reviewed and the issue would come up. I said I had something to tell her and she said, “I know what it is, you’re going to get married.” "Um, not exactly." There was a long build up and eventually I told her. She said, “I knew if you were anything like your father you’d be a sexual beast, and if there were no women there must have been men.” She was genuinely uninterested in sex once my father left her, she cut that side of her entirely out of her existence. She didn’t want to meet my boyfriends. When eventually she did meet one he died and she got very, very upset about that, and was great, actually.

Do our mums and dads fuck us up?

Certainly in my case. “They don’t mean to, but they do.” When you’re younger you make an accommodation that gets you through life, a kind of sense of self that’s just a working model for getting through the day, and then it starts to unravel a bit. You realise that you didn’t have to pretend to be this or deny yourself that – that’s all intimately bound up with my mother in a way I haven’t completely fathomed yet, but I will. My mother was a very eccentric person. We had such a combative relationship. I always put her away from me - now she has dementia, on the contrary, I look after her. But she was peculiar and erratic and wrong-headed in many, many ways. My father was long gone by the time I came out. He would have been appalled by my sexuality, but then he was appalled by everything to do with me, really, and the world as it had come to be.

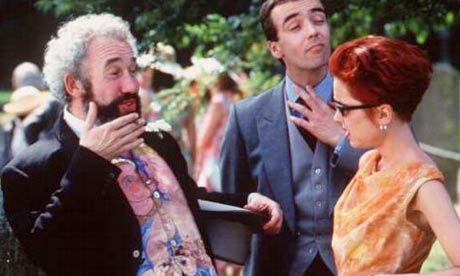

Most people will instantly identify you as Gareth in Four Weddings and a Funeral (pictured left). Is it inevitable that all actors have to live with A Defining Role?

Most people will instantly identify you as Gareth in Four Weddings and a Funeral (pictured left). Is it inevitable that all actors have to live with A Defining Role?

The phenomenon of DVDs and cable TV means that people see films over and over and over again. There are people who have seen Four Weddings 50 or 100 times, who know the film and my performance much better than I do. I’ve seen it once and liked it very much. It doesn’t date because of the very thing that certain people criticised it for at the time – it’s set in a kind of never-never land. Like almost all romantic comedies, it’s never actually of the minute it’s in, it refers to an archaic England that may never have existed. I’m perfectly happy to be identified in the public imagination as Gareth because a) it was a very well-written character, b) a terrifically good film, and c) it did a whole lot of favours in the area of the image of gay people. It was not stereotypical, and he was involved in the relationship that was the only true marriage in that whole circle. So that was all fantastically good. It’s disappointing for people when they meet me because they expect me to be Gareth, and I’m not. They beam with delight because they think I’m going to jig around the room and shoot off a series of jolly cracks. Well, that’s acting for you.

Is it frustrating that much of the rest of your work exists almost in the shadow of that film?

I remember getting a cab in London when I was directing an opera, Puccini’s Trittico. The taxi driver said, rather aggressively I thought, [Assumes lurking cockney tone]: “What you doin’ at the moment, then?” I said I was directing an opera. “Opera!” he said. “I thought you was light comedy!” And I suppose there are people who do think that.

Your colleague in Waiting for Godot, Patrick Stewart, has had this whole other life as Jean-Luc Picard in Star Trek. Is that kind of hugely populist television role something you would enjoy?

In the Eighties I did three series of a sitcom [Chance in a Million] which I loved. It’s just come out on DVD and it really stands up. Again, it’s never-never land, it doesn’t age at all. What I’d love to do is play a character like Rumpole - they’re always lawyers or detectives, aren’t they? Some character that's a sort of prism for people’s imagination and lives, that becomes a part of their landscape. One thing actors can do is create a definitive image of a certain human being who becomes archetypal. That’s the dream that one has, and Gareth is the only character who hit that jackpot. It’s a jackpot that I’d like to hit again.

Do you fear for the arts under a Conservative-led coalition looking to penny-pinch by whatever means possible?

I’m not party political in the tribal sense. I always voted Labour until the last election when I voted Liberal because I was exasperated by Labour in pretty well all its manifestations. They made such unbelievably, egregiously stupid mistakes. I mean, there’s no guarantee that because you wear a badge that says Labour that everything you do will be guided by God; clearly not. I’ve never ever had that tribal thing, which many of my contemporaries do: “Oh, Tories: shit!” Kneejerk, I hate all that. I think the idea of collaboration between parties is an excellent thing.

I’m naturally terrified that they’ll do root and branch damage to the structure of arts funding, but the arts establishment has been doing a fantastically good job. I have a sense that there’s genuine excitement and an approach which is very lively. We’re lucky, we’re blessed in that. But of course, as Nick Hytner quite rightly says, the National will be fine, the RSC will be fine and the Royal Court will be fine. London will be fine. London is always fine. It’s the rest of the country that one worries about. The loss of the repertory companies is one of the most tragic things that happened to the acting profession, to audiences, and to writers. It was incredibly fertile, all of that. It was killed by government action, by Thatcher’s rate-capping, which enabled local councils to see reps as an expense they could get rid of. It was such a bad thing for the life of our cities.

I’m naturally terrified that they’ll do root and branch damage to the structure of arts funding, but the arts establishment has been doing a fantastically good job. I have a sense that there’s genuine excitement and an approach which is very lively. We’re lucky, we’re blessed in that. But of course, as Nick Hytner quite rightly says, the National will be fine, the RSC will be fine and the Royal Court will be fine. London will be fine. London is always fine. It’s the rest of the country that one worries about. The loss of the repertory companies is one of the most tragic things that happened to the acting profession, to audiences, and to writers. It was incredibly fertile, all of that. It was killed by government action, by Thatcher’s rate-capping, which enabled local councils to see reps as an expense they could get rid of. It was such a bad thing for the life of our cities.

What do you think when you look in the mirror?

That 61 is not such a vivacious thing to be. Physical problems, knees and hips, are tiresome, and I hate the idea of having to think about everything and having to be cautious. On the other hand, I couldn’t give a damn any more about what anyone thinks about me in terms of my personality or my work. Some critics have a well-established dislike of my work. Too bad. It doesn’t worry me in any sense. Everyone at this age must be thinking there ain’t a lot of time left. I have a huge amount that I want to write and I have to plan it. I have to finish Welles, there’s a memoir I just have to write, a couple of novels – I really need to get on with all that stuff. I suppose I have a curious feeling that what I’ve lived through has been amazingly rich and complex and contains lessons, and I want to somehow disgorge all that, to debrief myself on what I know about life. That’s all we’re really doing as actors or as writers. Trying to say: “This is what I found out.”

Comments

...