When You're Strange: A Film About The Doors | reviews, news & interviews

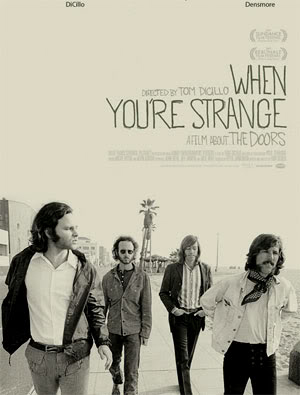

When You're Strange: A Film About The Doors

When You're Strange: A Film About The Doors

Great footage and terrible cliches collide in Doors documentary

Tuesday, 29 June 2010

It was the Danny Sugerman-Jerry Hopkins biography, No One Here Gets Out Alive, that kicked off the Doors death cult 30 years ago, at a point where the band's reputation was wallowing low in the water. Previously it had been quite acceptable to regard much of their work as cheesy pseudo-jazz with stupid lyrics, and their posturing vocalist Jim Morrison as a tedious drunk with a Narcissus complex.

Then suddenly The Doors were propelled into Classic Rock nirvana, their collective efforts elevated to "Great American Band" status and Jim Morrison canonised as sage, seer and sex god. There they remain, and if Oliver Stone's cosmically bombastic The Doors wasn't enough, Tom DiCillo's new hagio-doc should suffice to keep the memorial flame burning for the foreseeable future. And as the director reminds us, The Doors still sell a million albums a year.

DiCillo believes that "The Doors' music is the rock equivalent to film", and has "great drama, sex, poetry, and mystery". Morrison, who studied film at UCLA and nursed cinematic pretensions, would be flattered, and Di Cillo has knitted chunks of Morrison's short film HWY into the fabric of When You're Strange. In fact, he's done Morrison a favour, because the snippets of Jim wandering by a Mojave desert highway, preposterously clad in fleece-lined leather jacket and skin-tight leather trousers, and shots of him aiming his battered GT 500 Mustang towards the horizon in finest Two Lane Blacktop style, are used far more effectively here than in the incoherent original.

Indeed, the flick's strongest suit is the way DiCillo has constructed it entirely from authentic period footage, much of it aired for the first time, eschewing posthumous reconstructions and resisting any inclination to conduct new interviews with surviving band members, rock critics or what have you. Mind you, that hasn't prevented him from adding his own narration, which is riddled with garish journo-babble about Morrison being "like an ancient shaman", or "The Doors made music for the uninvited", and intoned with don't-you-dare-laugh earnestness by Johnny Depp. As for the device of showing Jim listening to a news report of his own death on his car radio, there are of course those who believe that he's running a beach bar in Belize as we speak.

But hats off to DiCillo and his crew for their sterling work in the research and archive department. The band's life-span up to Morrison's death in 1971 is thoroughly covered, from their formation in Los Angeles and their early gigs, through sequences of them working in the studio with the progressively more drunk or acid-crazed Morrison, to scenes of their greatest notoriety when Morrison fell foul of the law at gigs in New Haven and Miami. And there are The Doors performing "Light My Fire" on dear old Ed Sullivan's show (how on earth a guy resembling a bastard half-brother of Richard Nixon and Gordon Brown ever became TV's Mr Showbiz is worth a film in its own right), and Morrison crooning the smarmy "Touch Me" in front of a squad of old guys in suits playing horns and violins. Not very Lizard King that day eh, Jim? Notable, too, is the way the other Doors are given credit for their musical skills and for managing to find ways to get through live performances with their increasingly unreliable singer.

But hats off to DiCillo and his crew for their sterling work in the research and archive department. The band's life-span up to Morrison's death in 1971 is thoroughly covered, from their formation in Los Angeles and their early gigs, through sequences of them working in the studio with the progressively more drunk or acid-crazed Morrison, to scenes of their greatest notoriety when Morrison fell foul of the law at gigs in New Haven and Miami. And there are The Doors performing "Light My Fire" on dear old Ed Sullivan's show (how on earth a guy resembling a bastard half-brother of Richard Nixon and Gordon Brown ever became TV's Mr Showbiz is worth a film in its own right), and Morrison crooning the smarmy "Touch Me" in front of a squad of old guys in suits playing horns and violins. Not very Lizard King that day eh, Jim? Notable, too, is the way the other Doors are given credit for their musical skills and for managing to find ways to get through live performances with their increasingly unreliable singer.But evocative and nostalgic as the period footage is, especially some beautifully grainy black-and-white interview material, the film has no ambitions to pick apart The Doors mythology or get inside the turbulent group dynamic as Morrison's wild ride headed for its watery denouement in a Parisian bathtub. Their drummer, John Densmore, wrote a rather good book about his life in the group (Riders on The Storm), confessing his feelings of guilt that nobody ever seriously tried to help Morrison handle what can now be seen as glaring psychological problems, but When You're Strange is all about the legend. The sequence where DiCillo has intercut a live performance of "The End" with a string of famous fatalities, from Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King to Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix, announces the triumph of melodramatic grandstanding over documentary film-making.

- When You're Strange is on release

- An exhibition of photographs of The Doors' early years, including previously unseen images, is at the Idea Generation Gallery, 11 Chance Street, London E2 from 5 July to 27 August

- Find The Doors on Amazon

Add comment