Journey Through the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, British Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Journey Through the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, British Museum

Journey Through the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, British Museum

Gods, monsters, mummies, magic spells and the sweet hereafter

Those ancient Egyptians, they loved life! So much so that they even conceived of an afterlife that differed hardly at all from the one on Earth, only better: they didn’t get sick and they carried on just as before, to eternity – which might sound like a bore to some, but given that the average life expectancy for an ancient Egyptian - even a very rich one - was 35, a certain reluctance to leave the earthly realm was understandable.

In the divine realm of The Field of Reeds, the lucky few would drive their oxen, plough the fertile fields and paddle their boats. If they didn’t fancy doing much of that – though presumably they didn't get tired, either – they would get their servants to take over. However, you might have guessed that this probably wasn’t how the average pharaoh spent their days, but in the spirit realm it seems they took on the role of a kind of divine Everyman. This was the kingdom of the gods, where the upper echelons of society could indeed also become gods, free to enjoy all the natural riches of a paradisal Egypt. But before they got there, they had to repel all kinds of danger, and this is where the Book of the Dead came in.

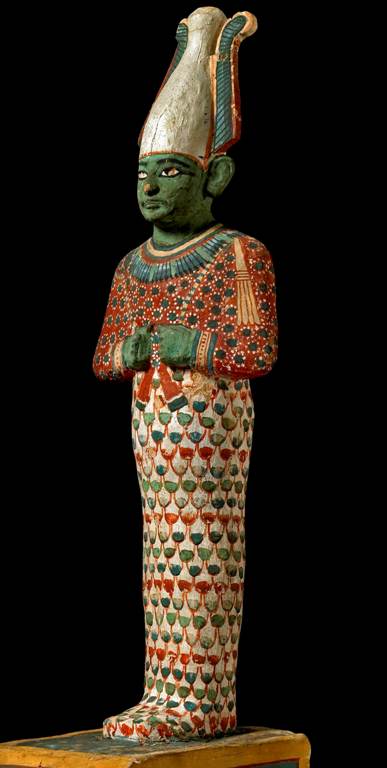

The Book of the Dead (it wasn’t called that at the time, but was named by a 19th-century German scholar) isn’t a single text, but a compilation of spells – 150 of them discovered to date. These equipped the dead with the knowledge and the power to guide them safely to the hereafter. The illustrated papyrus scrolls that accompanied the dead on their hazardous journey were rolled up, bound tightly and secreted about the mummified body, or, in later centuries, popped into a container, just like the small painted wooden figure of the god Osiris (pictured right), the king of the Netherworld (this one belonged to Anhai, a woman from a powerful priestly family who died in about 1100 BC). Osiris’s counterpart was the sun-god Ra, and both were guarantors of immortality.

The Book of the Dead (it wasn’t called that at the time, but was named by a 19th-century German scholar) isn’t a single text, but a compilation of spells – 150 of them discovered to date. These equipped the dead with the knowledge and the power to guide them safely to the hereafter. The illustrated papyrus scrolls that accompanied the dead on their hazardous journey were rolled up, bound tightly and secreted about the mummified body, or, in later centuries, popped into a container, just like the small painted wooden figure of the god Osiris (pictured right), the king of the Netherworld (this one belonged to Anhai, a woman from a powerful priestly family who died in about 1100 BC). Osiris’s counterpart was the sun-god Ra, and both were guarantors of immortality.

The British Museum’s scholarly but thoroughly accessible exhibition takes us on a labyrinthine journey through the different stages to divine immortality. On the way we encounter the ritual artefacts that made this complex journey possible: funerary statuettes (shabtis) that worked on behalf of their dead owners in the afterlife; hybrid deities with the heads of animals and the bodies of humans who acted as protectors; gilded mummy masks; magical amulets; and scrolls and scrolls of papyri containing spells. And you'll even find a popular board game for the living, called Senet (translating as “passing” or “passage”) which echoed the obstacles and challenges that faced the soul (ba) after death.

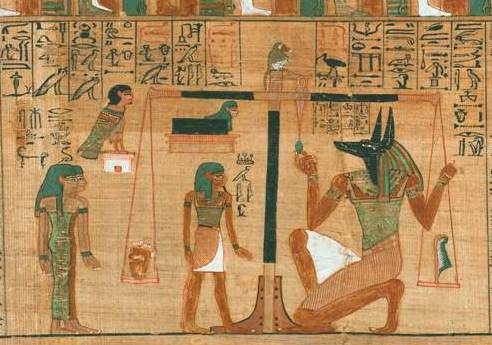

The final challenge was the weighing of the heart (pictured left: Papyrus of Ani, c 1275 BC). Placed on a set of scales, the heart was weighed against an ostrich feather. If the heart was heavy with sin, and the scales tipped, then the newly dead would soon find themselves in the jaws of the Devourer, a creature with the head of a crocodile, the upper body of a lion and the lower body of a hippo. To us, the Devourer looks no more terrifying than a pantomime horse, but to the ancient Egyptians this monstrous creature spelled the end of the road to immortality. Terrifying.

The final challenge was the weighing of the heart (pictured left: Papyrus of Ani, c 1275 BC). Placed on a set of scales, the heart was weighed against an ostrich feather. If the heart was heavy with sin, and the scales tipped, then the newly dead would soon find themselves in the jaws of the Devourer, a creature with the head of a crocodile, the upper body of a lion and the lower body of a hippo. To us, the Devourer looks no more terrifying than a pantomime horse, but to the ancient Egyptians this monstrous creature spelled the end of the road to immortality. Terrifying.

What this exhibition highlights is that these scrolls were often thoroughly individualised manuscripts, each furnished with the deceased owner's own choice of spells. If you were very rich, then you'd get your own personalised Book; if you were not so wealthy then your family could purchase an almost ready-made one (blank spaces would be filled by a scribe with the owner's details). Here we find one measuring over 37 metres in length. The Greenfield Papyrus (named after one Mary Greenfield, whose husband purchased it in the 19th century) was made for one of the most important women in Egypt, Nesitanebisheru, daughter of the High Priest of Amun PinedjemIi (c 990-969 BC), and so is highly personalised.

But, however fascinating you may find this exhibition - and no doubt you'll learn an awful lot - you'll still probably leave feeling that this is a culture that remains as remote and as strange to us as ever. Complex belief systems attached to the hereafter are not, after all, the rumbustious stuff of everyday life that brings such temporally remote cultures alive to us.

- Journey Through the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead at the British Museum until 6 March, 2011

more Visual arts

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Add comment