Q&A Special: Actor Derek Jacobi | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A Special: Actor Derek Jacobi

Q&A Special: Actor Derek Jacobi

As he takes on Lear, the actor knight recalls a long and glorious career

Derek Jacobi (b 1938) grew up in Leytonstone. His father was a tobacconist, his mother worked in a department store. Although he entered the profession in the great age of social mobility in the early 1960s, no one could have predicted that he would go on to play so many English kings - Edward II, a couple of Henry VIIIs and Shakespeare’s two Richards - as well as a Spanish one in Don Carlos. This month he prepares to play another king of Albion: Lear, against which all classical actors past a certain age must finally measure themselves.

His most momentous role in cinema is as an English queen, Francis Bacon in John Maybury’s Love is the Devil. But cinema, give or take the odd role in Gosford Park and Gladiator, has been less kind to him than television. The part with which Jacobi is abidingly linked is that of a Roman emperor. BBC Radio 4 have just started a new version of I, Claudius. It finds Jacobi ditching the famous stammer to play Augustus Caesar. He also played the lead in Cadfael, ITV’s popular medieval sleuthing drama.

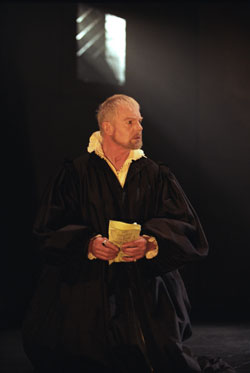

In recent years Jacobi’s best work has been seen in the theatre, where he has been getting noticeably and progressively nastier. The air of cuddly vulnerability which settled on him in the 1970s and brought women of a certain age flocking to his stage door has evaporated as he has taken on Schiller’s Philip II (pictured right), the irascible title role in John Mortimer’s A Voyage Round My Father and, most recently, Malvolio. King Lear unites him yet again with Michael Grandage, who directed both Don Carlos and Twelfth Night.

In recent years Jacobi’s best work has been seen in the theatre, where he has been getting noticeably and progressively nastier. The air of cuddly vulnerability which settled on him in the 1970s and brought women of a certain age flocking to his stage door has evaporated as he has taken on Schiller’s Philip II (pictured right), the irascible title role in John Mortimer’s A Voyage Round My Father and, most recently, Malvolio. King Lear unites him yet again with Michael Grandage, who directed both Don Carlos and Twelfth Night.

Jacobi's light-blue eyes can, indisputably, do the most piercing basilisk stare in the business. But in person his humility is refreshingly genuine. As a founder member of the National Theatre, he learned at the feet of Laurence Olivier, whom in 11 years he never called anything other than Sir, that pulling rank is unattractive in actor knights. He talks about his half-century in acting with theartsdesk.

JASPER REES: You have a hugely distinctive face. Could you describe it?

DEREK JACOBI: It’s a moon face. It’s round, fairly shapeless. I ask Father Christmas for cheekbones every year. He never sends them. And it’s now dropping. My eyes, I’ve been told – I think the term is ‘best feature’. They are very blue. They’ve always been rather baggy, which I’ve always hated. But I would never do anything about that. When I was younger I put the occasional egg white on them. It’s called Botox now, I suppose, but in my day it was egg white. I don’t like my face. I’ve never liked how I look. I rarely look in the mirror. When I was a teenager I had terrible acne and I couldn’t bear to look in the mirror. I remember at home we had a bookcase that had glass doors. If I needed to do a tie I would look in that because I could see a reflection of myself but I couldn’t see any of the spots. My Hamlet was very acne-ridden. The spots stayed around till late teens. Then miraculously they stopped coming. I can’t look at myself on the telly. I’m just constantly disappointed in myself. I don’t look or sound or express what I thought I was doing. And you can’t change it. I started life as a redhead. I’ve got a redhead’s complexion. As I grew older the red faded away and it became ash blond. The young Claudius was my own hair, teased and tweaked and buggered about with. But I’m not ambivalent about Claudius at all. I owe it so much.

Including your very large and loyal female fanclub.

I don’t know that it’s that large. I’ve probably played quite a lot of victims in my time and I think it maybe brings out the maternal in the ladies. They were there for Kean. Oh I loved that play.

But they couldn’t mother you in that. The great actor had a monstrous ego.

No, they couldn’t. I genuinely think that they just like seeing me on the stage.

Can you predict the front row on the first night?

In places like the Pit or the Minerva, those small venues, when you walk out and can see and touch the front row and it’s identical every night, that can become a bit… tedious isn’t the right word. You just think of all the people who couldn’t get a seat because they block-booked or something.

And then they wait for you at the stage door.

Yes. They are very generous. There’s not more than about – those that are still living, because they have been around for a long time – 25, 30. But they rarely come at the same time. They are past the autograph stage.

Does anyone call you Sir Derek?

Derek. Or Del. Delboy. I was Del when I was at school. The only two people who regularly call me Del in the business are Edward Hardwicke and Maggie Smith. I have hardly any family left now.

Do you know about the origins of your surname?

I tried to trace it back but I couldn’t get very far. My great-grandfather came to this country at the end of the last century from Germany. The name is very common in Germany and I got it back to northern Prussia.

Is it Jewish?

I think way back it must have been. We’re not Jewish as far as I know. Maybe when my great-grandfather came over perhaps from some sort of pogrom the name was a couple of syllables longer. It’s curious that the name with a Y is almost always Jewish but with an I rarely.

You’re from Leytonstone…

David Beckham country. Frank Muir, Johnny Dankworth, John Lill. Quite a lot of us.

Did you grow up with the same vowels as Beckham?

I don’t know when the vowels actually changed. The family talked east London. My mother was born and bred in Hackney. My two theories about it are that between the ages of nine and 11 for 18 months I had a form of rheumatic fever which confined me to bed for about 11 months. So long that when I got out of bed I had to walk on crutches. And during that time I was in bed and listened to the radio. I think those BBC accents had a great influence on me. Also my best friend at school was the son of the local pharmacist and they were posher than our family. They all spoke terribly well. That was an influence because I spent a lot of time with them.

Did your parents show dismay that you appeared to be bettering yourself?

Did your parents show dismay that you appeared to be bettering yourself?

No, but I was a bit of an anomaly at school. They couldn’t quite understand me. I looked like a yob and I had the full Tony Curtis quiff and the blow waves and the beetle crushers and the drape jackets and all that. I looked like a teddy boy but I didn’t sound like one. And I also at school acted and read the lesson, so at the same time they were thinking I was a bit sissy for acting and I sounded a bit strange, they would also come up to me and say, "Where d’you get your ‘air done?" They couldn’t quite suss the two. I didn’t sound as I looked. But it was never really a problem and I can’t really explain why. I wouldn’t have to fake the pedigree at all. It’s just as things have turned out I’ve done a lot of classical work.

Were you a frequent theatre-goer as a child?

I was very lucky. I went to the local grammar school. In those days there were a great deal of school parties. I remember seeing Wolfit as Lear and that wonderful season at the Old Vic in the Fifties. I remember seeing Burton play Hamlet and Henry V and Caliban. Also in east London I was taken to see a lot of Joan Littlewood at Stratford in Bow.

Do you know why you became an actor?

Somehow a gene – I don’t know where it came from – the night I was conceived got in there. My parents were nothing to do with the arts in any way. And as a child I played in the street, dressed up in my parents’ clothes and played imaginary games. It was all imaginative scenarios that we created. And the wind changed and I stayed like it. But it was always there.

Did your parents take you to the theatre?

Not a great deal. They did take me when I was about seven or eight to the London Palladium to see Cinderella. It was in the days of principal boys and a lovely actress called Evelyn Laye, very famous, was playing Prince Charming and another very famous actress called Noelle Gordon was playing Dandini. At one point they came down into the auditorium looking for kids to take back up onstage to give them a balloon and some chocolates. Well, I was one of the kids they took up. And so my first appearance was at the London Palladium. There was a lovely little coda to it because many years later they were laying a plaque in Westminster Abbey to Noël Coward and I was asked to go and read some of his war diaries as part of the ceremony. And sitting in the front row was an 85-year-old Evelyn Laye. So I went up and said, "You won’t remember me but we have appeared on the same stage together."

Did you know even then as a boy?

I hoped I was good at it. I said to myself, and I didn’t quite believe myself, that if I could get into the profession that I’d give it five years. And if I was still living on fish and chips twice a week then I’d give it up and teach history. I’ve never really believed myself when I said that. I remember as a very small child I first appeared onstage when I was six at the local library, but I remember writing to Sir Michael Balcon at Ealing Studios asking to be in films. I must have been eight or nine. And writing to television people. Writing to producers. Actually Balcon’s secretary did reply. "Sir Michael thanks you for your letter and we think you’re a little young at the moment but when you’re older…" I really have been lucky. Circumstances have fallen.

Jacobi as Hamlet:

I think it was. And then the school play and all that. It was an all-boys school. I had to do my stint playing ladies before my voice broke. And only the second male part I played at school was Hamlet. The first male part I played was a new play called The Last of the Incas. It was long before Royal Hunt of the Sun. I played one of the Spanish conquistadors. I was 17 going on 18. I tore the passion to tatters. What I lacked in expertise I made up in volume. Another fortuitous meeting was with Burton. I also played Hamlet when I was at university and we took it in the vacation to Europe and one of the places we played it was Lausanne which is where Burton lived. He knew Claudius so he came round afterwards and was very complimentary and said to me, "You’ve got to roughen your voice up. You’ve got a voice like me, it’s a bit mellifluous, you’ll send them all to sleep." When I got back to Cambridge he’d written me a letter and in it he said if ever I wanted to turn professional to contact him and he’d see what he could do, which was great. So when I did two days on a film years later I reminded him of this and he said, "What are you doing now?" I said, "I’m about to play Hamlet at the Old Vic." He said, "I’ll come and see you."

And he did. He came round afterwards and stayed in the dressing room, invited me out to dinner, so we left together and as I was walking down the corridor behind the stage he said, "Do you mind if we go and stand on the stage?" So there I was standing next to Burton on the stage, him having just seen my Hamlet, and I said, "I sat up there and watched your Hamlet when I was a schoolboy." He said, "Yes, I remember Churchill coming to see it and when I got to 'To be or not to be' he started saying it loudly." This was a night to remember. All he wanted to do was talk about the theatre and Shakespeare. Films didn’t come into it. We had dinner, we went to a nightclub because his stepson was playing the saxophone somewhere. It was a great night. I played Hamlet twice at the Vic - 1977 and 1979. The National had already moved to the South Bank by then. I played it on television in 1980 with Claire Bloom playing my mum Gertrude whom I’d seen again as a schoolboy playing Ophelia to Burton’s Hamlet in the Fifties. So I got to play Hamlet nearly 400 times.

Did you carry spears as a young actor at the National?

No, I was incredibly lucky. Olivier came on a talent-scouting thing around the reps and I was at Birmingham Rep and he saw me play Henry VIII and offered me a job at Chichester. That was the summer of 1963 and that October was the first National Theatre at the Vic. I was Cassio. That first production at the Vic was O’Toole’s Hamlet and Jeremy Brett was down to play Laertes and I was the understudy and Jeremy Brett was bought out by Warner Brothers to play Freddie Eynsford-Hill in My Fair Lady and instead of replacing him with a like star they upped the understudy. So my first role at the National was Laertes.

Is it true Olivier dropped his voice by an octave to play Othello in that inaugural production at Chichester?

There was a lovely voice teacher at the National called Kate Fleming and Kate did indeed drop his voice a couple of octaves and he not only came to the first read-through with his new voice but also head to foot in black leather. He sat there and John Dexter said, "Go for it." There was Maggie Smith and Frank Finlay and all of us sitting there absolutely shitting ourselves and Sir Laurence did the full thing. It wasn’t just a read-through.

Jacobi as Cassio in Othello:

Why did he need to blow you lot out of your seats?

I think he’d been preparing for about seven years. I think like all actors he was scared, he was frightened and he wanted to say, "I’m going for it." The marvellous thing about being in a company like that was we all knew each other and trusted each other and we could embarrass ourselves in front of each other. It could have been awful but it was wonderful actually. But it was jumping in at the deep end. All those pressures on the man. That company in the October became the first National Theatre, almost to a man. I was there for nearly eight years, till 1971. And also remember I’d been three years at Birmingham Rep. Eleven years I wasn’t out of work. A young actor. And work with the cream of the profession. So it was a huge learning curve. Work with Gielgud and Scofield and Redgrave and Sir Laurence. We were made to feel we were at the centre of the universe. Maggie and Albert [Finney] had given up West End careers to sign three-year contracts. Joan Plowright, Billie Whitelaw, Geraldine McEwan, Anthony Hopkins. We were the kids of the company. Why give up a job like that? We were on Olympus. Learning and acting with these wonderful people - it was a great experience. The youngsters in the company were very much encouraged by Sir Laurence. Tony [Hopkins] was the first one who left and became a film star.

And was never forgiven?

I’ve got great admiration for Tony. I once had to take over a part from him and I couldn’t do it. It was Andrei in Three Sisters. He walked out on several occasions and was always welcomed back. When I eventually left the National in 1971 and they gave me my National Insurance card I thought they were giving me green-shield stamps. I didn’t know what it was.

And most of your generation have since been given knighthoods and damehoods.

The knighthood came out of left field. I truly didn’t expect it. I did think long and hard about it. There are very, very eminent performers who’ve had the courage to turn it down, because it is a big, big temptation. It’s a measure of distance travelled. And if you are at all conscious of, and proud of, where you started and finished, it’s a symbol of that. Is it a worthwhile symbol? Do you rate it as a symbol of achievement? I do and I did. That’s why I marked the box that said "Yes". It was a consideration that it would separate me. But I decided that would be up to me and how I conducted myself and how I used or did not use it. And I don’t use it in that sense.

But I remember meeting Sir Laurence for the first time. I’m not equating myself with him. But I remember meeting him and shaking his hand and he eyeballed me and held my eyes until I, of course, dropped mine, by which time my shirt was sticking to my back. I thought, that’s not going to happen. None of that. He was a bit naughty. He had many hats and many faces. He was my employer, fellow actor, director, friend, father figure. But he used his known charisma and power and abilities and position to cajole, intimidate and encourage but when he wanted to put you down he could. But the eyes were very hypnotic. There came a time in his relationship with most actors when he’d say, "Call me Larry." I could never call him Larry.

Talking of Hopkins, what do you recall of going up for the part of Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs?

I went to see Jonathan Demme in LA. I knew within 30 seconds that I hadn’t got it. You can tell. It’s a look in their eyes. They go ever so slightly dead. Ever so slightly "no, it’s not going to work". He was very sweet. He thought, I mustn’t make this actor feel unwanted. So we talked for about five minutes. "Lovely to meet you, thank you very much." I’d love to play the lead in a big movie. I have absolutely no regrets that it didn’t happen. I’m very happy. I’m talking from a position of great privilege. I am an actor who has worked fairly consistently.

You suffered from stage fright in mid-career. How long did it last?

It stayed with me for three-and-a-half years. It is a sort of disease, I suppose. The RSC cured me. I hadn’t been onstage and one of my ambitions had always been to work at Stratford and I was out in Bavaria playing Hitler. The call came to go and play four incredible parts. I knew that if I said no, I would never have gone onstage again. I had to face those demons. So I did it. It was by facing the problem. It wasn’t easy.

The wider world became aware of you because of Claudius.

I started in 1960. And Claudius was 1976 so I'd been at it for 16 years. I’d done a couple of tellies. My parents were overjoyed because the neighbours suddenly knew what she was talking about, because till then I could have been working for the National Coal Board. "National Theatre, what’s that?" But suddenly I was being beamed into their living rooms twice a week.

"Evidently quality of wits is more important than quantity": Jacobi in I, Claudius:

How good a part was it?

Stunning. I didn’t at first think it was going to be. There were 13 episodes and they sent me the first seven. I had to audition for it in a strange way. London Films owned I, Claudius. It was an American company. There was a time when Charlton Heston was going to pay the older Claudius. There was a time when Ronnie Barker was going to. But suddenly they decided they wanted the same actor so the audience went through with hm. I’d done something on television called Man of Straw. The producer and the director were the same for I, Claudius and they said, "What about Derek?" But then the American people said, "Who?" They wanted somebody known. I was totally unknown on telly. I had to go out and have dinner with this guy and act my socks off for him over dinner and try to persuade him to take a chance. And it was a chance to take. I just charmed the pants off him somehow. I convinced him that I could do it. I had two wonderful advocates who were battling for me. They sent me the first seven episodes and I thought, this is the slowest burn of any part, because up until episode eight or nine Claudius was there, he was around, it was nice, but it was all about everybody else. Claudius was there but he wasn’t the focus by any means. Until about episode nine he started to build and build. But it was wonderfully written and graduated in that way so by the time Claudius became Emperor the audience were rooting for him to survive and make it.

Did you meet Robert Graves?

I’d met him once before. My parents never went abroad. They always went to Torquay or Babbacombe or something. I once persuaded them to go to Mallorca. They would only go if I would go with them. I was working at the National at the time. I said, "All right, I’ll go for two weeks," and prepared to be bored out of my skull. One day I’m lying on the beach in Palma sunning myself and I sit up and there at the water’s edge – I must be hallucinating but it’s Maggie Smith. And I stand up and it is Maggie. I rush down the beach. I say, "What are you doing here?" She points out to sea and there’s a yacht out there and she says, "You see that? I came on that. I’m staying with Robert Graves in Deia. I’m sure he’d love to meet you. Come up for the weekend." So that’s what I did. I said to my parents, "You’ll be all right for two days."

It was an extraordinary weekend. His family were there and Ava Gardner was there. The actor who played the first Jesus Christ in Hollywood movies whose face you saw - Jeffrey Hunter. I got on very well with Robert and then years later he came to the BBC while we were doing it but he was a bit gaga by then and he wasn’t really with us. We had lunch and he didn’t mention anything, came down on the set. The only time he seemed aware of what we were doing was when he went up to George Baker and said, "You’re the right height for Tiberius." And then at the end he sent the BBC a telegram saying, "Claudius is very pleased." He thought he had a hotline through to Claudius.

Did you watch it?

Did you watch it?

I didn’t watch it at the time. When the first episode was screened we were working on episode seven and I remember the critics were very iffy to start with. It wasn’t a big success. By the end it was what it became. It was very difficult for us because we were only just halfway through. I didn’t watch it till about five years later, I was in Los Angeles, and I was forced to sit down and watch the whole lot over a weekend. It was wonderful actually. It was like visiting old friends. This must have been 1980, 1981.

Have you seen it again?

I’ve seen bits. We had a reunion in 1996, 20 years on, and they showed an hour’s worth of clips and we all shrieked. Often the best parts are the victims and he was the victim par excellence, and the one that the audience are rooting for. He’s got everything against him, everything to fight for, and he’s the big survivor, and all the people who’ve got it all lose it. And there is this disabled, stuttering, twitching creature who is not worth killing.

How easy was it to find that stutter and twitch?

I was at university with an actor director called Richard Cotterall and Richard had such a stammer. I didn’t then know there was a difference between a stutter and a stammer. I copied Richard’s stammer. Also the designer had an assistant who also had a stammer and I used to back him up against the wall and say, "Talk to me, talk to me." At first they sent me the first seven scripts and all Claudius’s speeches were written with three Bs. After a time they thought, this is a waste of time, he’s going to do his own thing. Also they showed me the documentary called The Epic that Never Was about the Laughton film which was never finished. There were various scenes filmed. The BBC showed me this just to get rid of him. "You’ve seen his twitch and his limp and his stammer. Now you do your own." There was a little boy playing me as an eight or nine-year-old called Ashley. One day we were watching him rehearse. Maggie Tyzack, who was playing my mother, said, "Look at Ashley, can you notice anything? He’s twitching the wrong way." So we told this poor little boy and he couldn’t cope. Very early on the young Claudius goes to the Sibyl to find out what is going to happen and Herbie Wise said, "How do we approach a Sibyl? I think you should raise your hands and bow your head and just do a couple of twitches," which I did and ricked my neck badly. So I had to have one of those collars. If you look at the earlier scenes in I, Claudius you can see the pain on my face.

Derek Jacobi as Alan Turing, also with a stammer, in Breaking the Code:

How much of a difference did the role make to you?

Huge, really. It gave me a foot in the door in America. Within three years I was starring in a play on Broadway. It was a Russian comedy called The Suicide by Nikolai Erdman. That would never have happened without Claudius. It bought a recognition of me as an actor. I became a known quantity.

You’ve worked with many directors. How was it to work with Noël Coward?

I was directed by him in Hay Fever. In the course of it he took everybody in the cast individually out for an evening. He took Robert Stephens, Lynn Redgrave, Maggie. My evening came along, we went to the theatre, saw a play, then we went back to the Savoy and had dinner. We went up to his suite, which he had permanently. They had given him a suite whenever he was in London because during the war a bomb fell very near the Savoy and Noël rushed up to the piano and started playing and calmed everybody down. The Savoy were so thankful they said, "When this war is over, whenever you’re in London you must come and stay here."

He was reminiscing and we were drinking whisky and I was getting very drunk. I had an early rehearsal the next day and eventually I said, "Noël, I have to go now." On the way to seeing me out he said, "Derek, could I ask you a very, very personal question?" Oh Christ, this is going to be a difficult situation. And I said, "Yes, Noël." He said, "Are you circumcised?" Oh dear, how am I going to get out of this? I said, "No, I’m not." He said, "Oh what a great pity." I said, "Why, Noël?" He said, "You are a very, very fine actor but you’ll never be a great actor until you are circumcised." "Why?" And he just said, "Freedom, dear boy, freedom." I was all for checking myself into the London Clinic the next day. But everybody said, "At your age it’s incredibly painful."

In the end all great English actors have a go at Hitler. How was it for you?

In the end all great English actors have a go at Hitler. How was it for you?

It was a very special Hitler in that it was a screen version. It was one of those American mini-series things and it was a screen version of Speer’s autobiography Inside the Third Reich. My agent sent me to meet the director. At the end of the interview he said, "We’d like you to play this part." I never was in the business of turning work down, but I said, "What is there about me that strikes you as being Hitlerian?" And he said, "We are making a version of Speer’s take on Hitler." Speer describes a Hitler that was domestic, very sympathetic, an actor, seen to be acting. At New Year’s Eve parties he would receive telegrams from the heads of state all over the world and he would read them out in the voice of the sender. He would mimic badly and everybody would laugh. They said, "You are an actor, we want to see you acting as Hitler acted. Anybody can look like Hitler, you’ll look like him as near as dammit."

We arranged to meet Speer, who unfortunately dropped dead in the Royal Lancaster Hotel the week before we were due to meet him. But it was fascinating doing it. We did it in the studios in Bavaria. Driving round certain areas of Munich in the brown uniform was very spooky. They had to have special permission to put up Swastikas. And the older people in the street would walk on the other side. The kids would all rush up and stand next to me and get their friends to take pictures of them with the Führer. There was one extraordinary day when they got 500 students from the university to act as extras. The scene was Hitler’s campaign to become chancellor. Hitler would come in with Hess and one of the others and give a speech to the students. It was a two-page thing I had to learn. At the end of it the students were asked to stand up and cheer and we did it and did the first shot, the whole speech. At the end they clapped, they cheered, and at least 50 per cent of them went "Sieg Heil". Which was absolutely chilling.

They gave me three weeks’ preparation and an office in the studios with a television and masses of tapes. I would sit in the office nine till five watching him and physically copying him. You can’t as an actor – or you shouldn’t – make moral judgements. I had to play him. I had to pretend to be him. Hamlet is a mass murderer by the end. He’s killed five people. You don’t play the monster, you play the man. It’s the same in Shakespeare. You don’t play the king. You play the man. And when you play a man, then you play the king. It’s the same with Hitler. You can’t make that judgement.

And yet you’re not necessarily known for playing characters with a nasty streak.

When I was cast as Cyrano de Bergerac (pictured right), which looking back on it was one of the best things I’ve ever done, certainly one of the most enjoyable, my initial reaction to that was, "No, no, no, I’m miscast." The first two acts of it he is a very, very angry man. I don’t think I had the anger. I thought I was too placid, too even-tempered. I can pretend because that’s the business I’m in but whether I had the resources to get there… But it was the director Terry Hands who got me there. When you play parts like that, when your initial reaction is "No, it’s not for me", if you make a go of it then you add another colour to your palette.

When I was cast as Cyrano de Bergerac (pictured right), which looking back on it was one of the best things I’ve ever done, certainly one of the most enjoyable, my initial reaction to that was, "No, no, no, I’m miscast." The first two acts of it he is a very, very angry man. I don’t think I had the anger. I thought I was too placid, too even-tempered. I can pretend because that’s the business I’m in but whether I had the resources to get there… But it was the director Terry Hands who got me there. When you play parts like that, when your initial reaction is "No, it’s not for me", if you make a go of it then you add another colour to your palette.

Did Francis Bacon fall into that category?

He did rather. Again I was surprised to be cast. I didn’t quite know why John [Maybury] had come to me. One of the reasons I think was that Francis Bacon was not the most attractive-looking man in the world and the fact that I sat in the make-up chair and five minutes later I looked like Francis Bacon might have been one of the reasons. That again was a part that I really had to reach for. But in a sense they are the most rewarding parts, where you carry with you a feeling of adventure and a feeling of having to strive for something, the end result of which you’re not sure of.

Watch the trailer for Love is the Devil:

In a career that has included many peaks, does it remain a sore point that you haven’t acted at the National Theatre on the South Bank?

It feels a bit odd. I’d love to. I’ve been approached. I think enquiries were made by P Hall, Richard [Eyre] and certainly by Trevor [Nunn] but nothing has ever been set up. I was asked to do one play and I very uncharacteristically turned it down. I just didn’t think I could bring anything to the play. I was out of sympathy with it. And I didn’t want my first time on the South Bank to be in something I wasn’t really committed to.

The National Theatre opened on the 22nd October, 1963, which was my 25th birthday. On the 22nd October, 2013, it’ll be the National’s 50th and my 75th. It would be nice to be in something that year. It’s always been somebody else suggesting things. I’ve never said, "I want to do that." But it doesn’t get easier. I think it gets harder. Expectation. It was great being young and an outsider not having to prove anything, come a good second, do well. But suddenly, when you’re a favourite, people are putting money on you.

- King Lear at the Donmar Warehouse until 5 February, 2011, then touring

- Find your nearest venue for NTLive broacast in cinemas to 22 countries on 3 February

- Find Derek Jacobi on Amazon

'It's as if I never left': Jacobi sends himself up in Frasier:

Rehearsal images by Mark Brenner

Comments

...