The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900, V&A | reviews, news & interviews

The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900, V&A

The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900, V&A

'Art for Art's Sake' credo explored through a cornucopia of earthly delights

A cult suggests unhealthy worship, and there’s more than a whiff of that in the heady decadence of the V&A’s latest art and design blockbuster, The Cult of Beauty. This is an exhibition which examines how the influence of a small clique of artists grew to inspire ideas not only about soft furnishings and the House Beautiful, but to influence a whole way of life, teaching the aspiring Victorian bohemian how, in the words of Oscar Wilde, “to live up to the beauty of one’s teapot”. And as one might expect, the exhibition is beautifully designed, in a way that suggests you might have stumbled into the secret, scented and darkly cavernous chambers of an aesthete Aladdin.

The Aesthetic movement can be neatly summed up by the phrase "Art for Art’s Sake". The inelegant translation from the French "L’Art pour l’Art" originated from the pen of Théophile Gaultier as early as the 1830s and was soon popularised by Baudelaire. There was no formative philosopher of the movement in England, though Walter Pater, an Oxford Don, would later write a somewhat “scandalous” response to it.

In 1873 he published a collection of essays, Studies in the History of the Renaissance. By the title alone you would never have guessed that it would be deemed a threat to young minds and that its writer would be brought swiftly to account by the university authorities. Arguing in his conclusion that the passion and intensity of one’s aesthetic experiences when regarding a work of art should be all-consuming, the suggestion was that any moral instruction was of little or no value. The exhortation to “burn always with this hard, gem-like flame”, certainly inflamed the Bishop of Oxford when he condemned Pater as a corrupting influence.

In 1873 he published a collection of essays, Studies in the History of the Renaissance. By the title alone you would never have guessed that it would be deemed a threat to young minds and that its writer would be brought swiftly to account by the university authorities. Arguing in his conclusion that the passion and intensity of one’s aesthetic experiences when regarding a work of art should be all-consuming, the suggestion was that any moral instruction was of little or no value. The exhortation to “burn always with this hard, gem-like flame”, certainly inflamed the Bishop of Oxford when he condemned Pater as a corrupting influence.

Yet in no sense did the movement begin as an intellectually cohesive one. Instead, it loosely sought to promote a set of aesthetic ideals, whose direct inspiration could be found in the works not of a theoretician, but of a painter: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the founding artist of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Gathered in a close-knit circle were a group of artists, craftsmen, designers, architects and medievalist romantics whose beliefs chimed with the radical ideals of the PRB. They wanted to do away with both the sententious moralising of mainstream Victorian society and its crass materialism. And, among the craftsmen, there was a desire to redress the poor standards of design that had made the young William Morris leave the 1851 Great Exhibition in some disgust. All wanted to rediscover the joy of pure beauty – the "Art for Art’s Sake" credo – and the artists and designers in this stable numbered Edward Burne-Jones (Pictured right: The Golden Stairs, 1880), Frederick Leighton, Morris, GF Watts, EW Godwin and James McNeill Whistler.

We begin the exhibition surrounded by a parade of sensual, flame-haired beauties. These are the later canvases of Rossetti and his contemporaries. Bocca Baciato, 1859 (main picture) presents a turning point in Rossetti’s career, for it was the first of his pictures of single female figures and established the style that was to become a signature of his work.

The title’s meaning, “mouth that has been kissed”, refers to the sexual experience of his sitter, indeed his lover, the model Fanny Cornforth. Full of subtle symbolism, she is surrounded by marigolds, denoting grief, a rose in her hair, a symbol of love, and an apple in the foreground, foretelling of temptation and sin. Each, in its way, suggests the ephemeral nature of the subject’s beauty and touches upon the illicit nature of their relationship (Rossetti had been engaged to another of his models, Lizzie Siddal, whom he finally married the following year).

The title’s meaning, “mouth that has been kissed”, refers to the sexual experience of his sitter, indeed his lover, the model Fanny Cornforth. Full of subtle symbolism, she is surrounded by marigolds, denoting grief, a rose in her hair, a symbol of love, and an apple in the foreground, foretelling of temptation and sin. Each, in its way, suggests the ephemeral nature of the subject’s beauty and touches upon the illicit nature of their relationship (Rossetti had been engaged to another of his models, Lizzie Siddal, whom he finally married the following year).

Leighton’s painting Pavonia, 1858, is separated by just a few months. A fan of peacock feathers is spread out behind the dark-haired, sultry model. It is the aesthete’s favourite motif, for his is an art self-consciously absorbed in itself and existing merely to parade its own beauty.

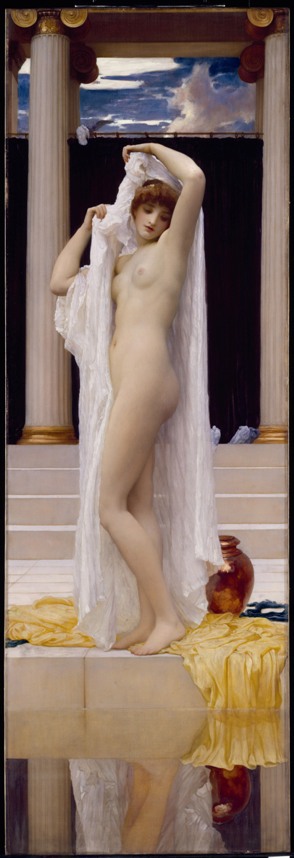

Leighton, a celebrity in his day, is certainly well-represented here. Included are two glorious, languorous nudes. His arresting The Sluggard, 1885, a bronze of a stretching male nude, fig leaf snugly preserving whatever modesty is left him, greets you as you enter the exhibition, while further along is the long, scroll-like canvas The Bath of Psyche, 1889-90 (pictured left). Here the subject’s milky flesh is reflected in a pond as she admires herself in its glassy surface. It is again a picture of utter self-absorption, but one in which we are invited to be excited voyeurs.

Whistler presents a contrast, since he was closely associated with the group yet his talents take him into another direction altogether. Where previously we seem to have been surrounded by paintings in high definition, as we enter this part of the exhibition we are immersed in chalky soft focus. And while Whistler's young girls in floaty white dresses, his “Symphonies in White” (Pictured right: Symphony in White No 3) are well represented here, we also, incongruously, find a luminous painting of Battersea Bridge, soft turquoise for the dimming light and steely, brooding grey for the hulk of bridge. Ruskin, who had been a great champion of the PRB in its day, famously accused Whistler of asking 200 guineas for “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”, and though it's rather difficult today to work out exactly what Ruskin's beef was, Whistler's resolute modernity sits rather uneasily amongst the other paintings here.

Still, the highlights of this exhibition are, indeed, its paintings, yet in amongst the Chinoiserie and Japonisme, there are also outstanding examples of truly innovative design. Godwin’s ebonised mahogany sideboard, 1865-75, might have been designed by De Stijl were it not for the dark, uniform colour, and Christopher Dresser’s angular, polished steel teapot would not have looked out of place in a Bauhaus-designed kitchen.

Still, the highlights of this exhibition are, indeed, its paintings, yet in amongst the Chinoiserie and Japonisme, there are also outstanding examples of truly innovative design. Godwin’s ebonised mahogany sideboard, 1865-75, might have been designed by De Stijl were it not for the dark, uniform colour, and Christopher Dresser’s angular, polished steel teapot would not have looked out of place in a Bauhaus-designed kitchen.

Finally, there’s the inevitable humorous backlash: the aesthete caricatured in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience; the wilting, limp-wristed aesthete as a teapot (pictured left: Royal Worcester, 1881); a cover for sheet music, with the words "Quite Too Utterly Utter" declaimed by an aesthete to his sunflowers as he theatrically clasps his hands to his breast. The movement had come of age, and while its designs and certainly its paintings could only be afforded by the few, its style ethos – its mode of dress, its Arts and Crafts jewellery and extravagantly flowery wallpaper - had become enduringly familiar to all. All I am left to say is: prepare to be pleasured.

Finally, there’s the inevitable humorous backlash: the aesthete caricatured in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience; the wilting, limp-wristed aesthete as a teapot (pictured left: Royal Worcester, 1881); a cover for sheet music, with the words "Quite Too Utterly Utter" declaimed by an aesthete to his sunflowers as he theatrically clasps his hands to his breast. The movement had come of age, and while its designs and certainly its paintings could only be afforded by the few, its style ethos – its mode of dress, its Arts and Crafts jewellery and extravagantly flowery wallpaper - had become enduringly familiar to all. All I am left to say is: prepare to be pleasured.

Explore topics

Share this article

more Visual arts

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Add comment