Taryn Simon: A Living Man Declared Dead , Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Taryn Simon: A Living Man Declared Dead..., Tate Modern

Taryn Simon: A Living Man Declared Dead..., Tate Modern

Portraits of Uday Hussein's double, a man with 9 wives and a feuding family

For her latest project, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I-XVIII, American photographer Taryn Simon spent four years searching out families the world over whose lives have been defined by circumstances largely beyond their control – not natural calamities like floods, fires or earthquakes, but events orchestrated by other people. The stories are extraordinary.

The title refers to the Yadav family from Utah Pradesh, India (pictured below). Four family members were declared dead by relatives intent on appropriating their farm. Land is in such huge demand there that the practice is common; but despite the proof given by Simon’s photographs that the men are still alive, corruption is so rife that once local officials have signed the necessary documents it is virtually impossible to get their testimony rescinded.

In Ireland Simon discovered Latif Yahia, who for nine years acted as the double for Saddam Hussein’s eldest son Uday. When the boys were at school together they were often mistaken for one another; in adulthood, Latif was forced to undergo plastic surgery to enhance the likeness so that he could assume the dangerous role of Uday’s stand-in. Since quitting the job, he and his family have been threatened by the regime and forced to live in hiding.

In Nepal, young girls chosen to be Royal Kumaris spend their childhood incarcerated in temples in the Kathmandu Valley where, decked in elaborate finery, they have their feet kissed by worshippers. On reaching puberty, though, they are returned to their families probably to languish in poverty because of the belief that marrying a Kumari results in death. Along with the photograph of a former Royal Kumari, Simon includes the picture of a 58-year-old woman who has retained her position because she claims never to have menstruated.

Joseph Nyam Wanda Jura Ondijo from Kenya has nine wives, 32 children and 63 grandchildren. While, he says, two of his wives were chosen for love, the rest were acquired alongside goats and cattle as payment for the treatment he gave for problems such as infertility, Aids and possession by evil spirits.

The Ferraz and Novacs families from north-east Brazil have been locked in a feud since 1913. The dispute is over power; members of both families seek to dominate the political scene by standing for mayor and gaining other prestigious local government positions. So far the feud has claimed the lives of 20 family members plus 40 others including friends, hit men and innocent bystanders.

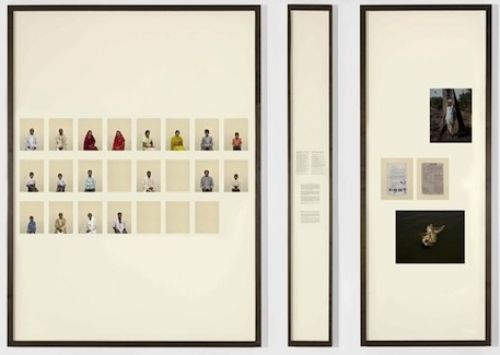

The scope and ambition of Simon’s project is impressive, so is the way she turns portraiture on its head. Instead of focusing on individuals or tightly knit groups as one might expect, she presents people as elements in a bloodline. The living ancestors and descendants of the subject are photographed seated against a neutral backdrop. Those who couldn’t or wouldn’t attend the photo shoot are represented by their clothing or a blank space or, in the case of the Mehic family from Bosnia, whose relatives were killed in the July 1995 massacre of Muslims in Srebrenica, by their bones or teeth.

The stories she uncovers may be dramatic enough to excite even the most jaded tabloid journalist, but Simon’s forensic approach makes the work as dispassionate as a lab report. The portraits are printed small and displayed in a grid so that individuals are reduced to specimens, like butterflies pinned to a board or entries in an encyclopaedia and, in the absence of any signs of mutual engagement, the relationships which nurture people are rendered all but invisible. The effect is extremely unsettling; each person seems very much alone, imprisoned in the solitary confinement of their neutral frame; yet, at the same time, their fate seems sealed by their genealogy. In this setting, blood relationships seem more like a curse than a blessing.

The portrait panels are flanked by annotations (pictured left) listing the names and occupations of those photographed and outlining their family history, while a third footnote panel fleshes out the social, political or historical context of the events described. These panels bring home just how disconcerting is Simon’s orderly presentation. A footnote photograph of eight of Joseph Ondijo’s wives standing together in a cluster immediately arouses interest and sympathy; the portrait grids, on the other hand, reduce people to a regimented sequence of anonymous ciphers trapped by their heritage.

The portrait panels are flanked by annotations (pictured left) listing the names and occupations of those photographed and outlining their family history, while a third footnote panel fleshes out the social, political or historical context of the events described. These panels bring home just how disconcerting is Simon’s orderly presentation. A footnote photograph of eight of Joseph Ondijo’s wives standing together in a cluster immediately arouses interest and sympathy; the portrait grids, on the other hand, reduce people to a regimented sequence of anonymous ciphers trapped by their heritage.

A series focusing on children from a Ukrainian orphanage differs from the rest by featuring those whose blood ties have been lost or severed. A framed inscription in the history classroom reads: “Those who do not know their past are not worthy of their future”, which seems to pour scorn on the orphans’ lost inheritance and callously to abandon them to an undesirable fate. The accompanying notes confirm that when they leave the orphanage the children are likely to fall victim to people traffickers and child pornographers or to work as prostitutes. Paradoxically, though, this set of photographs seems more animated and the subjects more individualistic than any of the others.

Taryn Simon has been described as one of the best photographers in the world. She made her name with ambitious projects such as The Innocents (2003), for which she photographed people who had mouldered for years on death row for crimes they did not commit. In each case photography had played a crucial role in wrongfully incriminating the suspect. An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar (2007) involved photographing places in the United States not normally accessible to the public. A luxuriant crop of cannabis grows in a government laboratory; radioactive capsules are stored in water at a nuclear waste facility; a Palestinian woman undergoes surgery to have her hymen restored and, frozen inside capsules at the Cryonics Institute, the dead await resuscitation at some auspicious future date. As in A Living Man Declared Dead... Simon’s detachment from her subject produces images that are so hyper-cool that, despite the excitement of glimpsing hidden realms, they are hard to engage with.

Engaging ideas explored with extreme dispassion; it's an odd combination that for me makes Simon more a conceptual artist than a photographer. The 18 sections of A Living Man Declared Dead... are referred to as chapters and, before being turned into an exhibition, each of her projects has appeared in book form, which is how they work best. The massive tome accompanying the Tate exhibition is a far more user-friendly way to view the project. With only a few portraits printed on a page, one can view the people as individuals and engage more fully with them and their plight.

This is far more desirable, but I’m not sure that it makes Simon’s point. The message of this latest project strikes me as extremely dark. One chapter consists of pictures of rabbits caught in Queensland, Australia (pictured right) and injected with virulent new strains of a disease as part of a biosecurity project designed to eradicate the unwelcome species. Twenty-four rabbits were introduced into Victoria in 1859, but with no natural predators to control them, their numbers have since multiplied to half a billion. The inclusion of rabbits invites us to view ourselves as a species rather than as individuals or families and implies that, if left unchecked, human population growth will present as severe a threat to the wellbeing of our planet as the rabbits do to the Australian outback. It's just as well that this explosive message comes coolly packaged; otherwise it would cause uproar.

This is far more desirable, but I’m not sure that it makes Simon’s point. The message of this latest project strikes me as extremely dark. One chapter consists of pictures of rabbits caught in Queensland, Australia (pictured right) and injected with virulent new strains of a disease as part of a biosecurity project designed to eradicate the unwelcome species. Twenty-four rabbits were introduced into Victoria in 1859, but with no natural predators to control them, their numbers have since multiplied to half a billion. The inclusion of rabbits invites us to view ourselves as a species rather than as individuals or families and implies that, if left unchecked, human population growth will present as severe a threat to the wellbeing of our planet as the rabbits do to the Australian outback. It's just as well that this explosive message comes coolly packaged; otherwise it would cause uproar.

- A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I-XVIII at Tate Modern until 2 January, 2012

Share this article

more Visual arts

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Add comment