BBC Proms: Ax, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Haitink | reviews, news & interviews

BBC Proms: Ax, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Haitink

BBC Proms: Ax, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Haitink

Refined musicians who put beauty and fellowship before dangerousness

"O, reason not the need!” cries Shakespeare’s King Lear, insisting on certain unquestioned rights. The phrase came to me listening to Bernard Haitink conducting Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto and Fourth Symphony last night. The 82-year-old Haitink does not question the need for this music - and I’m not sure that’s entirely right. I want the imperative there, I want to feel the urge to be born in those musical paragraphs that Brahms wrote with such generous largesse. To reason the need gives the music its birth again.

So this was an evening of exceedingly velvety, light-fingered Brahms, of exquisite finish and tailoring in what I’d call a modern cut, with the smallish Chamber Orchestra of Europe (a band of orchestral principals), and an approach that doesn’t linger on melodrama or large-scale pianism as some of the past Brahms interpreters used to. It’s hard to conceive of the Second Piano Concerto as chamber music, but when you hear that sublimely tranquil slow movement with the cello and the sparse lower strings accompanying it, chamber music is what it can be, and Emanuel Ax, the soloist, is a chamber musician by instinct, which is what makes him a great one.

Though 20 years younger than Haitink, the Polish-born American played the concerto in total partnership with the conductor, as if they shared a single pair of ears, the entire thing conceived to trip more lightly than one might sometimes hear. This comes, I feel, at a cost to tension, to the chiaroscuro dramas of the music. I sense Haitink’s mellowness caps off Ax’s occasionally more passionate impulses, a serenity smoothing all.

The excitement, as such, came from hearing a master pianist carrying off all that titanic pianism so lyrically and unfussily in cahoots with his conductor and orchestra, rather than with a charismatic dramatist’s instinct luring us hither and thither, playing with the tension of the score, duelling with the orchestra like a ship with a turbulent sea (which, you’ll gather, is rather the way I like it more). Few pianists have a more delicate yet copious control than Ax, those massy chords full-blooded and absolutely clear, the mazy touch in the mysterious shadows of the Scherzo, arpeggios dreamily harp-like in the Andante.

He is a genial man - he dragged the slow movement's solo cellist William Conway forward at the end again and again, beaming at the player’s elegiac eloquence, and one felt the entire experience had been, as indicated, a chamber performance of utmost artistry, pianist and conductor putting fellowship above all. Terrific qualities, though there are other more exciting approaches, riskier ones, where the Andante movement is not quite so calmly flowing, life not so imperturbable, where tempi are not quite so measured in the arrestingly unquiet Scherzo and the dancing finale, where the sections’ differences are more pointedly contrasted and a few of the notes thrown to the winds in order to saturate the colours a little more Byronically.

Watch Emanuel Ax play Brahms's Intermezzo in A from Op 118

If anything, Haitink’s conducting of the Fourth Symphony after the interval was even more mellow. It lends itself, with that plaintive opening theme, to his gentle, reassuring touch, under which the COE’s violins came across with exceptional refinement in the Albert Hall, but I frequently felt that Haitink was so intent on underemphasis that he undercut the bass. There was playing that was texturally wonderfully polished and flowing, with few of the starts, held breaths and pauses that bring out the suspense between those fully formed paragraphs of Brahms’s, particularly in the first two movements. The music luxuriated, highlighting the Baroque echoes, well adjusted, well balanced, particularly with the strings. I fancied that Haitink was more dynamically engaged with the winds, solo players whom he cues and plaits together like singers (he is one of the great opera conductors).

Perhaps the plethora of wind voices was why the last movement sprang alive with a bursting excitement and taut atmosphere that I hadn’t felt in the rest of the evening, the way Haitink conjured and tightened the suspense in the dangerous fractional spaces before a brass player sounds his note, the way he lured flute and oboe to resonate with tragedy in those meandering little cries that seem to recall wounded creatures, the insistently visceral questions to which the symphony’s opening query has been converted. By the end I was profoundly moved by this old man’s urgency with the music, a communion of life force that most certainly reasoned the need.

As a postscript, I do echo my colleague Igor Toronyi-Lalic in his objection to some obtrusive, vulgar production values at the previous Brahms Prom with these forces. Last night we had pink and lilac splodgy light-projections poured around the back wall of the orchestra, LED light strips in purple and gold like something from an IKEA Christmas sale, and most of all some darned intrusive filming. With the flamboyant ceiling light racks, a giant camera gantry wheeling about on the right like a crane, and chaps whizzing about to catch a little close-up of the triangle, it was all rather like watching a concert on a building site erecting a stadium rock platform.

- This Prom is broadcast again on Radio 3 on Monday at 2pm

- Listen again to it for the next seven days on the BBC iPlayer

- theartsdesk's pick of the Proms

- theartsdesk's BBC Proms 2011 complete listings

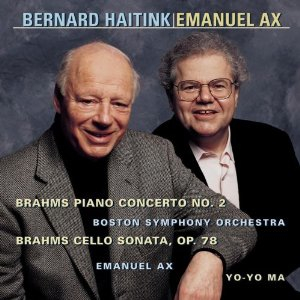

Find Ax and Haitink's recording of Brahms' s Piano Concerto No 2 on Amazon

Find Ax and Haitink's recording of Brahms' s Piano Concerto No 2 on Amazon

Share this article

Add comment

more Classical music

Christian Pierre La Marca, Yaman Okur, St Martin-in-The-Fields review - engagingly subversive pairing falls short

A collaboration between a cellist and a breakdancer doesn't achieve lift off

Christian Pierre La Marca, Yaman Okur, St Martin-in-The-Fields review - engagingly subversive pairing falls short

A collaboration between a cellist and a breakdancer doesn't achieve lift off

Ridout, Włoszczowska, Crawford, Lai, Posner, Wigmore Hall review - electrifying teamwork

High-voltage Mozart and Schoenberg, blended Brahms, in a fascinating programme

Ridout, Włoszczowska, Crawford, Lai, Posner, Wigmore Hall review - electrifying teamwork

High-voltage Mozart and Schoenberg, blended Brahms, in a fascinating programme

Sabine Devieilhe, Mathieu Pordoy, Wigmore Hall review - enchantment in Mozart and Strauss

Leading French soprano shines beyond diva excess

Sabine Devieilhe, Mathieu Pordoy, Wigmore Hall review - enchantment in Mozart and Strauss

Leading French soprano shines beyond diva excess

Špaček, BBC Philharmonic, Bihlmaier, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - three flavours of Vienna

Close attention, careful balancing, flowing phrasing and clear contrast

Špaček, BBC Philharmonic, Bihlmaier, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - three flavours of Vienna

Close attention, careful balancing, flowing phrasing and clear contrast

Watts, BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Bignamini, Barbican review - blazing French masterpieces

Poulenc’s Gloria and Berlioz’s 'Symphonie fantastique' on fire

Watts, BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Bignamini, Barbican review - blazing French masterpieces

Poulenc’s Gloria and Berlioz’s 'Symphonie fantastique' on fire

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Comments

...