The Faith Machine, Royal Court Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

The Faith Machine, Royal Court Theatre

The Faith Machine, Royal Court Theatre

Religion and commerce collide in Alexi Kaye Campbell's demanding new drama

A monolithic slab, like a giant incarnation of a Biblical tablet of stone, dominates Mark Thompson’s set for Jamie Lloyd's production of the third play by Alexi Kaye Campbell. Nothing else is so solid in this big, weighty work, which wrestles with abstract notions of faith, the human soul and the myths and narratives by which we choose to live.

It’s an ambitious piece of writing, and at times Campbell trips over his own verbosity. In an evening of nearly three hours’ duration, carved up by two intervals, it’s difficult not to wish at times that he had more full-bloodedly dramatised his ideas, rather than forcing his characters to sound off about them at length, in dialogue that sometimes feels forced and scenes that are often static. But there is a questing intelligence at work here, and no little wit; and Lloyd’s production does much to hack through and irrigate the drier thickets of polemic.

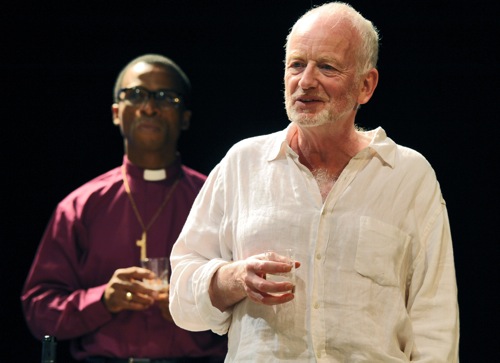

The first scene takes place in New York, on the morning of September 11. With tragedy about to be perpetrated by terrorists whose faith is so strong that they are prepared to die, and kill, for it, British Sophie (Hayley Atwell) is questioning the beliefs and morality of her American lover, Tom (Kyle Soller). Once an aspiring novelist, Tom now works in advertising – and he’s heading up a major campaign for a drugs company. The snag is that their products have been tested on Ugandan children – an inconvenient fact that careerist Tom is prepared to overlook, to the disgust of the appalled Sophie. As they argue, the ghostly figure of Sophie’s dead father Edward (Ian McDiarmid, picture below), a former Anglican bishop, stands between them – and it is his prompting that drives Sophie’s furious tirade of accusation. She offers Tom an ultimatum: pull out of the campaign, or she heads home. He chooses his job.

From here, the play shifts back and forth through time, testing the parameters of love and morality in a consumerist society. We see Edward, retired and living in a Greek island holiday home, and explaining in an excoriating confrontation with a Kenyan bishop who has come to attempt to coax him back to work that he cannot remain in a church that is homophobic. We see Sophie and Tom reunited at an English gay wedding: she has hooked up with Sebastian, a bearded Chilean communist; he is engaged to a skinny socialite interior decorator. In a lovely, poetic moment, Lloyd’s production sees the ex-lovers gazing at one another across a room of white and pink balloons, both sozzled on champagne and gently swaying. And we see Edward devastated by multiple strokes, still filled with passion, albeit unfocused, and despairing of being caught between the literalism of fundamentalism and what he sees as the hectoring of atheists who deny the religious the wonderment of their faith.

From here, the play shifts back and forth through time, testing the parameters of love and morality in a consumerist society. We see Edward, retired and living in a Greek island holiday home, and explaining in an excoriating confrontation with a Kenyan bishop who has come to attempt to coax him back to work that he cannot remain in a church that is homophobic. We see Sophie and Tom reunited at an English gay wedding: she has hooked up with Sebastian, a bearded Chilean communist; he is engaged to a skinny socialite interior decorator. In a lovely, poetic moment, Lloyd’s production sees the ex-lovers gazing at one another across a room of white and pink balloons, both sozzled on champagne and gently swaying. And we see Edward devastated by multiple strokes, still filled with passion, albeit unfocused, and despairing of being caught between the literalism of fundamentalism and what he sees as the hectoring of atheists who deny the religious the wonderment of their faith.

Whether the characters are groping for meaning in their personal relationships, in the political (Sophie’s activism and journalistic work in areas of conflict, Sebastian’s Marxism), in tribalism (Tom repeatedly labels himself as a New Yorker, as if it defined him), or in the pages of literature or the Bible, there is a powerful emphasis on the need to give shape and structure to existence. Lloyd’s production is engagingly acted, with Atwell giving Sophie an obstreperous quality that saves her from sanctimony, Soller brash, tactless, eager and excitable, and McDiarmid a particular pleasure as Edward, a formidable opponent capable of destroying an argument or interrogating a house guest under the guise of a social manner that appears most twinkly just when it is about to become terrifying. There’s a scene-stealing performance, too, from Bronagh Gallagher as Edward’s irascible, sharp-tongued Ukrainian housekeeper – even if her role, as a one-time prostitute who found salvation in the bishop’s home, feels like a schematic contrivance. This is ambitious, thoughtful writing; but amid all the speechifying, its themes cry out for less dogged reliance on the word, and more action.

Explore topics

Share this article

more Theatre

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre review - brave, yes, but also misguided and bizarre

Sheridan Smith gives it her all against near-impossible odds

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre review - brave, yes, but also misguided and bizarre

Sheridan Smith gives it her all against near-impossible odds

The Divine Mrs S, Hampstead Theatre review - Rachael Stirling shines in hit-and-miss comedy

Awkward mix of knockabout laughs, heartfelt tribute and feminist messaging never quite settles

The Divine Mrs S, Hampstead Theatre review - Rachael Stirling shines in hit-and-miss comedy

Awkward mix of knockabout laughs, heartfelt tribute and feminist messaging never quite settles

Add comment