Debate: Should Theatre Be On Television? | reviews, news & interviews

Debate: Should Theatre Be On Television?

Debate: Should Theatre Be On Television?

A Pinter theatre director and a Shakespeare TV producer have an intriguing discussion

The relationship between stage and screen has always been fraught with antagonism and suspicion. One working in two dimensions, the other in three, they don't speak the same visual language. But recent events have helped to eat away at the status quo. On the one hand, theatre has grown increasingly intrigued by the design properties of film. Flat screens have popped up all over the place, notably in Katie Mitchell’s National shows and at the more ambitious work of the ENO. Meanwhile, theatre and opera have been encouraging those who, for reasons of distance or price, can’t make it to the show itself to catch it on a cinema screen instead.

The New York Met and La Scala run a successful operation selling, depending on your point of view, cheap opera/expensive cinema tickets to see their work piped live into cinemas across the globe. Last year the National joined the fun with NTLive, beaming Helen Mirren in Phèdre and, most recently, Simon Russell Beale and Fiona Shaw into cinemas around the world this year in London Assurance. A Disappearing Number has also been shown live in cinemas across the country. Shakespeare’s Globe have memorialised their productions of Henry IV parts 1 and 2, as well as Henry VIII and The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Audiences, by the look of them, seem to have accepted the new dispensation without complaint. It helps that mobile High Definition technology has allowed cameras to get in and among performances unobtrusively. But for all of these initiatives, audiences are still required to travel to an auditorium. Other companies are trying to bring theatre into the living room. Digital Theatre have harnessed the internet to offer downloadable play performances. Shooting mostly in smaller spaces such as the Almeida and the Young Vic, they use multiple angles to offer a careful facsimile of the live experience. The small spread of plays includes Jez Butterworth’s Parlour Song and The Comedy of Errors.

On 12 December BBC Four screens the specially filmed version of Macbeth, Rupert Goold’s award-winning account starring Patrick Stewart and Kate Fleetwood. The producer is John Wyver, whose company Illuminations also made one of the hit broadcasts of last Christmas, the RSC Hamlet starring David Tennant. In this conversation about the relationship between theatre and television, Wyver discusses the marriage of theatre and television with the director Harry Burton, whose close working association with Harold Pinter is memorialised in Working With Pinter, an acclaimed documentary also released by Illuminations. Jasper Rees

Watch the Macbeth trailer:

HARRY BURTON: Where does this passion of yours come from for theatre on television?

JOHN WYVER: I’m of a generation that grew up with the idea that theatre was a key part of television’s output. Not the case now. But clearly through the 1960s, 1970s and even into the early 1980s, theatre plays presented on TV, either in new productions or in some kind of reconfiguration of something that existed in the theatre previously, were a very important part of TV’s cultural output. And there were good and bad ones, inevitably. But I saw some significant productions. When I started as a Time Out journalist at the end of the 1970s David Jones, the former RSC producer, was in charge of doing classic plays for three or four years at the BBC, and he did some wonderful, quite bold things. For example he got Alan Clark to direct Danton’s Death, to which Clark, who was a very distinctive film-maker, brought a completely compelling performance style and visual language. In a different context Jones also commissioned Harold Pinter’s script of Langrishe Go Down, starring Jeremy Irons and Judi Dench. These were wonderful pieces of TV and I am interested in continuing that tradition.

HB: Were the boundaries between stage and television less drawn back then?

JW: I think there was a very clear Play of the Month tradition: an established, classic text usually staged in the studio with a multi-camera recording, designed to give to the public who couldn’t regularly get to the theatre a grounding in the broad outline of English theatre. There were other things around that were a little more eccentric, but still drawing on theatre in a strong way. Richard Eyre did a production on TV of Trevor Griffiths’ Comedians which he had staged at Nottingham Playhouse a few years before, presenting it in a way that still preserved the sense that this text and production came from the theatre, and not trying to transform it completely into contemporary TV drama; not trying to impose the conventions of other kinds of drama, but respecting what a text, a performance and a production conceived for the theatre might do in a distinctive kind of way on the small screen – which isn’t to say simply documenting what happens in the theatre. There is a legitimacy to that, it’s very valuable archivally, but creatively it’s not interesting. What is interesting is to find some kind of hybrid that sits between theatre in its roundedness and the screen. And I think it’s a very interesting and compelling aspiration to work towards.

The opening of Richard Eyre's production of Comedians

HB: What’s the role of the audience in the television version?

JW: Clearly one thing you are doing is offering the television audience access to something many of them couldn’t otherwise participate in, and there’s a value in that absolutely. But in another way it fundamentally changes what the audience is responding to, and how. You’re no longer sitting in the same space, or sharing experiences, and you certainly no longer have the potential for in some sense intervening in it. There has been this discussion around the idea that one idea of the essence of theatre is the idea that, individually or collectively, the audience can impact on the performance. Clearly that happens in a very general way, through the audience’s laughter, or the audience’s focused silence; that feeds back into live performance, and that’s never going to happen in television terms.

So certain things are missing, absolutely. What’s gained? Numbers and impact clearly… possibly an individual’s more focused experience; perhaps the sense that watching TV, or sitting in a live cinema relay watching a performance from the National Theatre, may add a quality of enhanced concentration distinct from the often uncomfortable theatre experience. I don’t pretend in any sense it’s the same kind of experience. But, watching as an audience member, it can have equal value. I really resist the idea that watching a theatre play or any kind of rich and complex piece on the screen is in any sense a less valuable experience as an audience member. I simply don’t accept that.

So certain things are missing, absolutely. What’s gained? Numbers and impact clearly… possibly an individual’s more focused experience; perhaps the sense that watching TV, or sitting in a live cinema relay watching a performance from the National Theatre, may add a quality of enhanced concentration distinct from the often uncomfortable theatre experience. I don’t pretend in any sense it’s the same kind of experience. But, watching as an audience member, it can have equal value. I really resist the idea that watching a theatre play or any kind of rich and complex piece on the screen is in any sense a less valuable experience as an audience member. I simply don’t accept that.

HB: Yes, it’s clearly different, and very individual. I was thinking about Abigail’s Party (pictured above right) which so many people name as a key television experience. Exactly as you’re saying, it’s not pretending to be something else: camera movement is quite restricted, it’s probably a multi-camera shoot in the studio, and watching it is a different experience to watching that play in the theatre, but rich nonetheless, and a highlight for so many.

JW: Interestingly there, I’m 95 per cent certain Mike Leigh conceived it, developed it and directed it for television, and only later did it become a stage play. Because that was at a point when he was working very regularly for television and had hardly done any theatre, and hadn’t graduated to cinema. HB: Your Macbeth got a bit of stick the other night on the Newsnight Review show!

HB: Your Macbeth got a bit of stick the other night on the Newsnight Review show!

JW: Andrea Calderwood the other night in a discussion of our production of Macbeth said it didn’t work for her because it was “just not television”. Now that does seem to me bonkers. It might not be good television, it might not be - and I’m rather pleased that it isn’t - conventional television drama. But clearly it’s television! As Paul Morley said, to think that you might not expose Patrick Stewart’s extraordinary performance (pictured left) to a relatively wide audience in this way is sort of ridiculous, to think that might not happen because in some way you thought it was an illegitimate form. It’s crazy.

HB: There’s a wonderfully filmic opening out of the stage show. How did that evolve with Rupert Goold?

JW: The genesis of our two Shakespeare films was rather different, and what you see on screen is very different in relatively subtle - and for me - interesting ways. The Hamlet is a filmed stage production, whereas the Macbeth for me is a film from a stage production.

HB: That’s a nice distinction, but what drives it? Budget?

JW: No, they had comparable budgets, both shot on a three- week filming schedule, both shot predominantly with a single camera, i.e. not in the studio with multiple cameras. Nor are they shot multi-camera either live or recorded, as the recent NTLive shows have been. So they are very similar in that sense. For me it’s to do primarily with the screen language. The Hamlet tries to find individual shots which develop over a period of time, often with movement (and some cutting); individual shots intended to capture the contained, pulled-down stage performance, re-thought in performance terms for the camera; essentially, the stage performance on the screen. I think there are very few examples in this tradition, but it’s trying to film, with the single camera, what was on the stage - even though we’ve taken that into locations.

What Rupert has done with Macbeth is apply a much more filmic language. So the shots are much shorter, the language is built up using editing much more than by developing continuous shots, and it’s closer to the forms of film drama we’re familiar with on television now. The film language is in some senses more conventional because of that. That partly reflects Rupert’s interests as a director, it’s partly a reflection of a particularly visceral production of that play, which is indeed significantly more visceral that Hamlet. I think they both work very well, and maybe for many people the distinction will get lost. But actually for me there’s a very striking difference in the way in which the images work on screen, follow each other, and are juxtaposed. I don’t think one is superior to the other, although I think the approach Greg took on Hamlet is rarer in the tradition of presenting theatre on television.

HB: The Macbeth is really striking visually, in the lighting and use of colour. The lighting is sensational, and visually everything heightens and reflects Shakespeare’s language.

JW: I hope that’s the case. There was a very strong concern to hold onto the language and the texture of the performances that Patrick Stewart, Kate Fleetwood and the others had created; to enhance that, and it make it work for a pretty broad, contemporary audience as well. Of course you want to use the possibilities of the screen form that you’re working with. There’s never any sense in which you can use the screen in some kind of unmediated way to take something created for the theatre and put it on the screen. You’re always going to shape and change and shift that, and the more you’re in control. The more conscious of that process and rigorous you are in applying it, the better the result is going to be.

HB: I acted for a long time, and there is an adjustment from stage to camera.

To be on TV or not to be on TV - David Tennant's Hamlet:

JW: Unquestionably there is an adjustment, absolutely. But I don’t think it’s hugely difficult, particularly these days where almost all your colleagues and peers work interchangeably across theatre, TV and film, if they’re lucky. Very few people these days work exclusively in one medium or another. So most people are able to modulate their performance successfully with relatively little adjustment, I think. When people are extremely used to working with the film camera – someone like Patrick Stewart, or David Tennant – and highly conscious of what the film camera can do, especially when it’s three inches from your face, then you can get something quite special and particular. Not all actors have the opportunity to get that experience. But I think the approach we’ve adopted where we take something to a location, break it down and shoot it with a single camera shot by shot, encourages actors to do that modulation much more successfully than taking cameras into a theatre and shooting live. As I understand it, when they do that for an NTLive performance the actors are aware of the cameras, and probably aren’t playing it quite as big as they would to a normal theatre audience. They’ve still got a theatre audience there, and they’re still playing to that audience.

HB: But for NTLive the actors have probably had no more than one rehearsal with the cameras, and the one note they have probably been given about the cameras is "ignore them". Whereas on your single-camera location shoots the actor and the camera are going to relate to one another and integrate – which I think creates better storytelling.

JW: Absolutely. It makes it more expensive, of course. It costs at least double, maybe treble, to do a Macbeth or a Hamlet than an NTLive show. But you get a kind of precision, a rigour and clarity of storytelling which, however good the live director and camera team are, you’re not going to achieve in the theatre, and I think it’s really valuable to work in this way. Sadly, although the BBC has been very supportive in doing these two productions, there is these days very little belief within the broadcasting organisations that either classic theatre, or indeed contemporary theatre, has any real place on television. And I regret that enormously.

HB: What underpins that intellectually?

JW: It’s quite hard to understand. I’ve been in public discussions where Ben Stephenson (Head of Drama at BBC TV), has said, “I don’t think theatre works on television.” I think part of it is a rather fuzzy memory of some very bad theatre on television sitting in the backs of people’s minds. Probably if you asked them to pin it down they’d associate it with the BBC’s Complete Shakespeare, produced between 1978 and 1985, all 37 of Shakespeare’s plays, all done in the studio, all done in rather traditional ways, ultimately thought of as a creative disaster, but in fact full of interesting things. There are quite a lot of very unremarkable pieces of television there. But, where directors were able to work with the studio, there are some wonderful things – the Henry VI trilogy is fantastic.

HB: Strangely not repeated very often.

JW: Exactly! So I think there’s a legacy of bad theatre on television.

HB: But if you go to Sydney Newman’s Armchair Theatre, it’s as modern and as electrifying as anything on telly today.

JW: But even though he worked with Pinter and other writers working on the stage at that time, Newman’s Armchair Theatre, and then the BBC’s The Wednesday Play right at the end of the 1950s and beginning of the 1960s, that’s the moment when television shifts away from a deep interest in theatre. Newman was a very strong, iconoclastic producer. He’d come from Canada and was concerned to bring a very contemporary and immediate sense to drama. He wants to find a way for drama on television to talk very directly to a very wide audience. Prior to that, the theatre had been absolutely the place television looked to for almost all of its drama output. From Sydney Newman onwards there’s a sense in which he and others want to create new writers who are primarily focused on television, and find new forms about the world of the moment that are specifically and inherently televisual. It was unfortunate really that his series was called Armchair Theatre, and then at the BBC he and others created The Wednesday Play, all the while actually moving away from the theatre legacy.

Watch the whole of Cathy Come Home, one of Ken Loach's films for The Wednesday Play:

HB: Is it fair to say that they were inherently motivated by an interest in social issues?

JW: That’s right. They were a bit lefty. But we have to be very aware of the moment in which they made what they made. Sydney Newman arrives at the point of the Royal Court revolution – much mythologised, but still a very powerful shift in British theatrical life. So we’ve had Look Back In Anger, and we’ve now got a group of writers who are primarily leftist, who are trying to bring the contemporary world to the stage in a way that, notionally at least, had not been done with quite the kind of concentration and force that those writers were working with. Sydney’s very aware of that, and he wants to bring some of that energy and creative power to the screen.

HB: There are very few people working in television today with that sort of breadth of interest or vision. That’s true, isn’t it?

JW: These things are very dangerous! But I wonder how many drama executives go even occasionally to the Royal Court, or the Bush, or even to the Cottesloe when it’s doing a contemporary piece.

HB: So the danger is that television is hermetically sealed off from other influences, and doesn’t like the idea of people bringing those other influences in.

JW: I think television is very concerned to constantly reinforce its own position, its specificity.

HB: Its “brand”. Hence everything feels and sounds and looks the same?

JW: I think there’s a lot of truth in that.

HB: What would you consider to be a result in terms of viewing public when Macbeth goes out on BBC Four?

HB: What would you consider to be a result in terms of viewing public when Macbeth goes out on BBC Four?

JW: I don’t know, several hundred thousand. On its first run on BBC Two Hamlet (pictured left) was watched by 900,000 people from beginning to end at 5pm on Boxing Day. That is a real result, it seems to me: an awful lot of people watching three hours of very dense, complex, entirely uncompromised Shakespeare. I think that’s fantastic. I don’t know how many Macbeth will get. But these are figures well in excess of those seeing the play in a conventional run in the RSC repertory or at Chichester. Macbeth ran for six weeks at the Minerva, a theatre of 200 seats. So it’s a much broader audience.

I mean, I have a particular interest in plays originally written for the theatre being done on television. I’m very interested in what happens when a text that is originally conceived for a particular context is then represented in screen terms. But clearly there are a number of writers, Harold Pinter being very prominent within that tradition, who have worked both in theatre and in television, creating plays with a specific sense of them being done for one medium or the other. I’m quite intrigued to ask you, knowing Pinter’s work very well, what differences you can see between the work he wrote originally for television and the work he wrote originally for the stage, particularly at the end of the Fifties and the beginning of the Sixties, when there were several original plays done for television, for example A Night Out and The Lover?

HB: Ben Stephenson must be intimidated by the idea of a play like Pinter’s The Lover getting an audience of – what – 12 million?

JW: It’s a very different context, only two channels, and all that.

HB: Sure. But still, the nation tuning in to watch a play! I’m currently editing Pinter’s letters for Faber and Faber. So I’ve been looking at the fan mail and letters that came into his office after the TV plays were broadcast, and the amazing response from members of the public who had never seen his plays, never heard of him, writing to say, “You need to consult a doctor before you write another play, Pinter! You’re clearly a lunatic. P.S. The whole factory agrees with what I’m saying.” And other people saying, “How did you know about my life?” There’s this amazing feeling of his looking right through the veil and into the inner workings of human beings.

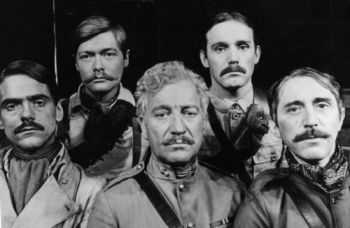

JW: What sense do you have of his interest in television? HB: Well, there’s quite a well-documented moment when Harold was I think preparing to direct Simon Gray’s play The Rear Column for the BBC (pictured right: Jeremy Irons, Simon Ward, Barry Foster, Clive Francis and Donald Gee in The Rear Column). He started to block with the actors and was talking to the floor manager and people when he said, “So, he’ll say that, and then he’ll walk across there…” At which point someone said, “Harold, if he does that then the camera will be in the shot.” So Harold said, “Oh. All right. Well, in that case, he can move there, and he can go there.” And they said, “Harold, if he moves there then that camera will be in shot.” At which point Harold said, “Ok. Stop.” They all went to a pub for an early lunch during which Harold took a quick class in camera direction for the studio. Then they went back and started again. So in a certain sense he was extremely interested in how television worked, and in how to apply his dramatic values – whether it was his or Simon Gray’s text – so that it worked.

HB: Well, there’s quite a well-documented moment when Harold was I think preparing to direct Simon Gray’s play The Rear Column for the BBC (pictured right: Jeremy Irons, Simon Ward, Barry Foster, Clive Francis and Donald Gee in The Rear Column). He started to block with the actors and was talking to the floor manager and people when he said, “So, he’ll say that, and then he’ll walk across there…” At which point someone said, “Harold, if he does that then the camera will be in the shot.” So Harold said, “Oh. All right. Well, in that case, he can move there, and he can go there.” And they said, “Harold, if he moves there then that camera will be in shot.” At which point Harold said, “Ok. Stop.” They all went to a pub for an early lunch during which Harold took a quick class in camera direction for the studio. Then they went back and started again. So in a certain sense he was extremely interested in how television worked, and in how to apply his dramatic values – whether it was his or Simon Gray’s text – so that it worked.

On the other hand, Harold was a gun for hire, extremely ambitious, and very excited to get his plays on at all, anywhere. So when people like Peter Willes said, “Come on, let’s give you a go,” Harold was still a very young man and incredibly eager to learn and experiment. I think The Lover particularly is in some ways, as a piece of television-specific drama, unsurpassed in its unpredictability for the audience, who sit riveted thinking what on earth is going to happen next? And he brought that from the theatre into the television studio. The originating impulse for Pinter to write a play probably came from the same place whether he was writing for television or the theatre.

Watch a clip from Harold Pinter's The Lover:

JW: But Pinter was unenthusiastic about exposing his process to television. I mean it was only towards the end of his life when you were able to bring him into that workshop to work with actors in front of the cameras. He’d not done that before because he’d been resistant to it? Or because no one had asked him? I can’t believe no one had asked him.

HB: I tend to believe that no one had asked him. When I said to him, “Would you do a workshop with me?” his first response was, “What’s a workshop?” I had to explain to him what it involved, because Harold was a writer, not a facilitator or a teacher. My impulse for making Working with Pinter was to facilitate for other people, including a television audience, the kind of experience I had when I was a young actor being directed by Pinter. Everyone should have this experience, so how can I facilitate it? But he’d just never been exposed to that way of working, because with him it was always the RSC or Peter Hall or the National. People just didn’t go up to Harold Pinter and say, “Can you come and teach a class?’ Of course I didn’t say to him, “Can you teach?” because he would have said, “I’ve nothing to teach.” Again, he wouldn’t have thought, “Oh, how interesting, let’s focus on the process.” He wouldn’t have thought like that. But being there, he actually found it absolutely fascinating, because he realised that the process in itself was enriching, to see actors taking those steps of discovery and being steered around; to feel how those observers were engaging with very raw and undeveloped work; that even at that early stage, things being discovered were meaningful to the audience/observers. JW: Actors working with text and a director is a very organic and often very internal process, sometimes working over a long period of time, full of unpredictable moments, shifts, changes and breakthroughs. Do you feel you can capture that with the camera?

JW: Actors working with text and a director is a very organic and often very internal process, sometimes working over a long period of time, full of unpredictable moments, shifts, changes and breakthroughs. Do you feel you can capture that with the camera?

HB: I do passionately believe that. I pitched a whole series around the idea of Working With. Alan Bennett agreed to do one with us. But we couldn’t find a broadcaster interested. We wanted to create a real archive. It was archivally driven from my side, because I really do believe that we’ve had a golden age and we’re not going to have much to show for it. I say “we”. I mean, you know, a couple of generations down the line. You see, if you don’t retain a living awareness of the values that people like Beckett and Pinter (pictured above left, with Harry Burton) and others really ran with in their time, then those values will recede, and what you’ll end up with is something much more received and generalised.

The whole thing about Beckett and Pinter is the specificity, the time taken, and the precision, and the organic-ness of that. I mean, I think there’s another thing about Peter Hall’s possible over-emphasis on pauses and silences, and the creation of a slight cult around Pinter. But I suppose that was probably inevitable at the time, given that they were originating, and people’s whole lives and livelihoods were forming around this new work.

In Working with Pinter Harold says of his silences and pauses, “I think they’ve been taken much too seriously.” I think that was Harold saying, “Please take my work and keep it alive, don’t let it become a mausoleum event.” But to answer your question, I do think you can record the process. You have to do it very, very carefully, and I think that famous series by John Barton about playing Shakespeare showed how not to do it, in the sense that it was pedagogical and terribly chummy, and the actors were quite well-known. I think the actors have to be not well-known, and it has to be driven by a willingness to share with audience, rather than teach or preach.

Watch a clip from John Barton's Playing Shakespeare (with subtitles)

JW: What are some of the other factors in that process? Do you need to work over a long period of time?

HB: On Working with Pinter I had the actors in the excerpts from the plays for two days before Harold came in. We had a three-day process. We filmed moments from the first two days. Out of kindness and respect for Harold, BBC Training and Development lent me my tutors from the BBC Directors Course to crew the third day. Harold came in and we filmed the third day’s rehearsals with several cameras. In other words, three 10-minute Pinter scenes had had two hours' rehearsal before Harold appeared. The actors were terrified. They couldn’t believe that Harold would allow them to be working at such early stage and be so raw. But of course what I was doing as a director and a facilitator was emboldening them. With my knowledge of Harold I was able to say, “He’ll support you. But you’ve got to commit and take a leap much sooner than you want to, and you’ve got to do it in front of these cameras, and in front of this audience of observers.” And the actors did it. And then Harold said, “That’s terrific. Now, what would happen if you tried that?” And at its best the whole thing became a sort of warp-factored, accelerated process where the moment of discovery was pulled wide open for everyone to see.

JW: To ask you a question you asked me earlier, what’s the value for the audience in that?

HB: Well, we have a lot of interview with Harold (there’s an extra on the DVD), reflecting on the workshop. With the benefit of a little bit of reflection I do think layers of the process are there for anyone who is curious. I think that’s the boon for the audience. They can actually once or twice see an actor go from being not sure, to "hang on, well maybe" to "bloody hell, this works!" and then getting a response from the author and observers.

JW: Does that enhance an audience’s engagement with Pinter’s plays, with theatre in general? Is that the aim?

HB: I think so. Because I am the audience – I mean, we who go to the theatre all the time are the audience, and I am dismayed when I hear practitioners talk about “oh the bloody audience,” because I think, that’s me you’re talking about! I go all the time. I can’t back this up particularly, but I think companies like Complicite and some of the "immersive" stuff that’s going on are sort of developments of this. I think we’re in a time when it no longer serves for the audience to go into the theatre and be told to "sit down, shut up and we’ll show you how to do it". I think that has lost its usefulness. I think what’s happened is that it has become so comfortable and so familiar that the basic transaction that must take place in the theatre, in the shared space, has ceased to be meaningful, ceased to have value. The transaction has become monetary and not spiritual, not soulful. And without that, without those higher stakes, theatre’s not worth much, because the thing that’s meant to happen isn’t happening.

Watch the filmic trailer for Complicite's A Disappearing Number:

And then you get this thing of practitioners – who know when it’s not happening – trying to pull the wool over the audience’s eyes. Now I think the audience is more intelligent than that, and I think it’s time to give the audience credit for understanding much more of the process, and relishing more of the process, seeing more of the process, being invited more into the process, for the reason that the process is enriched by the audience. And I think too often the audience is told that they are inexpert, unqualified, you’ve given money so sit down and be quiet. And Harold was guilty of that too, about coughing and so on. But a great Pinter audience is raucous! An audience at The Homecoming should be, because of the power of the language, by turns crapping its pants and laughing its head off, in an Elizabethan sense. And that’s why I love the fact that Illuminations is pairing Shakespeare and Pinter, and bring on Webster!

- Macbeth is on BBC Four at 7.30pm on 12 December

- Find Working with Pinter on Amazon

- Find the RSC Hamlet with David Tennant on Amazon

- Read John Wyver's blog on the Illuminations website

© Harry Burton 2010

'I don't think the author would approve' - Harold Pinter on acting in The Homecoming:

Add comment