Never the Same River (Possible Futures, Probable Pasts), Camden Arts Centre | reviews, news & interviews

Never the Same River (Possible Futures, Probable Pasts), Camden Arts Centre

Never the Same River (Possible Futures, Probable Pasts), Camden Arts Centre

Evocative exhibition curated by Turner Prize-winning artist Simon Starling

Simon Starling’s wonderfully eccentric exhibition Never the Same River (Possible Futures, Probable Pasts) will inevitably mean more to those who have visited the Camden Arts Centre regularly over the years. Places gradually acquire a patina of memories that accumulate layer on layer and infiltrate one’s perceptions in the present moment. Travelling round London, I encounter my past at every corner – the Slade where I spent many hours drinking coffee before being gripped with ambition to become an artist, University College Hospital where I gave birth, the house where I discovered how hard it is to be an adult, the doorstep on which a former lover confronted a future one, and so on.

The Camden Arts Centre played a significant part in all this, since I first showed there in an exhibition of young painters called Survey ’67. Since then I’ve been a regular visitor and each time I set foot in the first gallery, I remember when it was the reception area; I still see the video room as the former entrance, and recall the spacious café beside it and the stairs leading down to the toilets.

Starling also has a longstanding relationship with Camden; the building was designed by his great-great uncle. In 1999 he became artist in residence and, the following year, installed an exhibition that involved relocating a brick stove from the outside into gallery three. The architects who were planning the refurbishment of the arts centre at the time assumed the stove to be an original feature and included it in their design. This fortuitous mistake planted the seed of the idea for this exhibition, which treats the building as a three-dimensional palimpsest in which past and present collide. After many hours spent rifling through the archives, Starling chose nearly 30 works from those shown in the gallery over the past 50 years.

Even if you’ve never set foot in the building before, as soon as you enter the first space, you intuit that something odd is afoot. It looks as if the installation is still in progress unless, that is, the curator has no spatial awareness. Located on the spot they occupied the first time round, the exhibits are bunched awkwardly together as though they’ve just been delivered. And, in a sense, they have – from the past.

Made from recycled leather and fake fur and encased in an old-fashioned vitrine, Francis Upritchard’s spindly Sloth Creature (pictured right: shown here in 2005) looks like some aged exhibit exhumed from the store cupboard of a defunct museum of natural history. Cheek by jowl with this showcase stands the stump of a tree from the Burgess Park estate in south-east London (shown in 2006). Keith Coventry has memorialised its destruction by casting the stump in bronze and painting it funereal black to confer dignity on the remains.

Made from recycled leather and fake fur and encased in an old-fashioned vitrine, Francis Upritchard’s spindly Sloth Creature (pictured right: shown here in 2005) looks like some aged exhibit exhumed from the store cupboard of a defunct museum of natural history. Cheek by jowl with this showcase stands the stump of a tree from the Burgess Park estate in south-east London (shown in 2006). Keith Coventry has memorialised its destruction by casting the stump in bronze and painting it funereal black to confer dignity on the remains.

The most innovative designs often age the least well. The bentwood chair, nest of coffee tables and hat box designed by Marcel Breuer for Isokon, the firm that built the Lawn Road flats in Hampstead, were initially included in an exhibition titled Hampstead in the Thirties; even though some of these iconic designs are still available, they seem irrevocably stuck in the past. Ernö Goldfinger’s tubular steel and plywood stacking chair was also included in the Hampstead exhibition; having lost its radical edge, it now looks like any scruffy old school chair. In the brochure, Hampstead in the Thirties is listed as happening in both 1974 and 1975, a confusion which seems appropriate for an exhibition intent on disrupting one’s sense of history.

Two Willow Road, the house designed and lived in by Goldfinger, is preserved by the National Trust as a domestic shrine to Modernism. With everything carefully preserved, the interior is like a time warp; as the promotional video says, “You really do get a feeling that Goldfinger has just left the building.” John Riddy photographed the knick-knacks tastefully arranged on Goldfinger’s window sill and the view onto Hampstead Heath, which has changed so little since the 1930s that it would be hard to date the black-and-white image which was shot in 1998 and shown here in 2000.

Henry Moore had a similar collection of artifacts and natural objects. The inspiration for his pebble-like sculptures famously came from stones picked up on the beach. First exhibited at Camden in 1976, Half-figure (1932) now shares the room with two Norfolk flints cast in bronze by Des Hughes (shown in 2008) to parody or pay homage to Moore. If the first gallery focuses on spatial disruption, this one explores temporal confusion. As you go from work to work, references loop deliciously back and forth between then and now, and between art and nature, source and citation and the many spaces and slippages in between.

I remember finding Graham Gussin’s video (pictured left) annoying the first time round (in 1997 or 1998 depending on which date you select from the brochure). An idyllic view of a loch, the kind used to draw tourists to Scotland, is interrupted at random by a missile plummeting out of the sky, which happens so fast that you miss it. With anticipation followed by frustration, one becomes irritatingly aware that the present is an infinitesimally small moment between past and future that is easily missed. Which bright spark pointed out that we always live in the past because by the time we’ve processed incoming information it is already history?

I remember finding Graham Gussin’s video (pictured left) annoying the first time round (in 1997 or 1998 depending on which date you select from the brochure). An idyllic view of a loch, the kind used to draw tourists to Scotland, is interrupted at random by a missile plummeting out of the sky, which happens so fast that you miss it. With anticipation followed by frustration, one becomes irritatingly aware that the present is an infinitesimally small moment between past and future that is easily missed. Which bright spark pointed out that we always live in the past because by the time we’ve processed incoming information it is already history?

Mike Nelson has recreated an installation he made in 1998 during a residency. An array of oddities including biker helmets painted to resemble skulls and a Mickey Mouse head sprouting gazelle horns is arranged like an unfinished display of hunting trophies. Access is through a storeroom cluttered with junk – the raw material for additional items – which makes the assemblage seem even more provisional. Ironically, Nelson spent four weeks rebuilding this ad hoc display, as though he were a museum curator reconstructing the work of a dead artist.

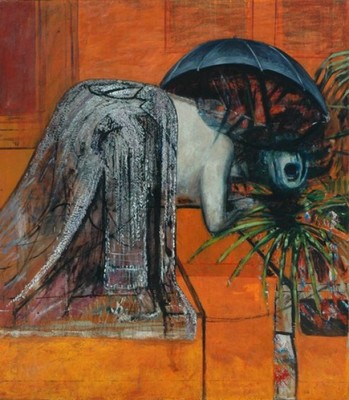

The only exhibits to resist the intrusion of unforeseen connections are the paintings, perhaps because they are physically self-contained. Francis Bacon’s Figure Study II , 1945 (pictured right: shown here in 1970) resists all attempts at appropriation; so do Hilma af Klint’s mystical watercolours which, although they were made in the 1930s, were first seen here six years ago and still feel fresh.

The only exhibits to resist the intrusion of unforeseen connections are the paintings, perhaps because they are physically self-contained. Francis Bacon’s Figure Study II , 1945 (pictured right: shown here in 1970) resists all attempts at appropriation; so do Hilma af Klint’s mystical watercolours which, although they were made in the 1930s, were first seen here six years ago and still feel fresh.

The star attraction, though, is a film David Lamelas shot in and around the arts centre in 1969. For anyone who remembers the Sixties as a libidinal love fest, this foray into the minds and mores of tight-lipped Londoners will come as a real shock. Asked what his feelings are about the imminent moon landing, a well-spoken chap replies “Feelings?” as if he’s been asked to drop his trousers in the Finchley Road. There it is in black and white – irrefutable evidence that my memories of the 1960s are wildly inaccurate.

What a joy to have one’s sense of time passed tweaked with such playful intelligence. Don’t miss this engaging exhibition.

- Never the Same River (Possible Futures, Probable Pasts), selected by Simon Starling, at Camden Arts Centre until 20 February, 2011

Share this article

more Visual arts

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Add comment