Newspeak: British Art Now, Saatchi Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Newspeak: British Art Now, Saatchi Gallery

Newspeak: British Art Now, Saatchi Gallery

It's a bit like the Royal Academy Summer Show trying to do 'edgy'

Wednesday, 02 June 2010

These days, it seems that approaching any new Saatchi exhibition, especially one that promises to be even bigger than all the previous ones held at the multi-galleried, three-storey Chelsea venue, makes the heart fairly sink. How much bigger, you want to ask, and why use size as a measure of anything? Surely there isn’t enough headspace to accommodate all those loud, clamorous, “look-at-me” artworks favoured by Saatchi all in one go? And this is just Part One. Part Two will be something to look forward to in late October.

I’m probably not alone in feeling this. After all, this isn’t the brash, confident Nineties, and British Art Now is certainly not going to herald a starry new YBA generation – who could go through all that again in a hurry? So Saatchi’s warehouse-sized adventures in art can no longer generate quite the same level of excitement or hot air, save only perhaps among the favoured artists themselves. And even then you wonder if this general air of exhaustion hasn’t infected them as well.

I’m probably not alone in feeling this. After all, this isn’t the brash, confident Nineties, and British Art Now is certainly not going to herald a starry new YBA generation – who could go through all that again in a hurry? So Saatchi’s warehouse-sized adventures in art can no longer generate quite the same level of excitement or hot air, save only perhaps among the favoured artists themselves. And even then you wonder if this general air of exhaustion hasn’t infected them as well.Certainly you get that impression as you walk into the first few galleries. In fact, it all seems fairly depressing, but not just because these works encapsulate a certain downbeat, reflective mood, but because they are non-reflectively mundane.

In the very first gallery, an inert, formless mess of Cellophane, clingfilm and crumpled paper by Karla Black seems to say only one thing - that the party’s already been and gone and we’re just here to clear up the debris. And the deflated mood continues elsewhere, with Hurvin Anderson’s weightless and nostalgic paintings of barber shops and empty beaches. In another room, Barry Reigate’s madly accreted paintings (pictured above right: Real Special, Very Painting, 2009) of manic cartoon faces, floppy penises and graffiti scribbles jostle with so much dense and frenzied imagery that they emit a kind of exhaustion. His “tar-bunny” sculptures, on the other hand, two of which have each been rudely skewered by fluorescent tube lights, would make a nice riposte to Koons' tacky pop-tastic cartoons.

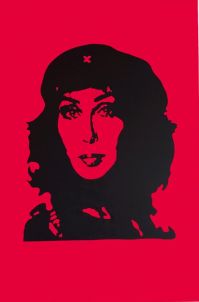

In the very first gallery, an inert, formless mess of Cellophane, clingfilm and crumpled paper by Karla Black seems to say only one thing - that the party’s already been and gone and we’re just here to clear up the debris. And the deflated mood continues elsewhere, with Hurvin Anderson’s weightless and nostalgic paintings of barber shops and empty beaches. In another room, Barry Reigate’s madly accreted paintings (pictured above right: Real Special, Very Painting, 2009) of manic cartoon faces, floppy penises and graffiti scribbles jostle with so much dense and frenzied imagery that they emit a kind of exhaustion. His “tar-bunny” sculptures, on the other hand, two of which have each been rudely skewered by fluorescent tube lights, would make a nice riposte to Koons' tacky pop-tastic cartoons.There’s more dreary stuff, this time dressed up with a slick adman sensibility, in Scott King’s Pink Cher (pictured left), a Warhol-style portrait with Cher in a Che Guevera beret. Why? Did Gavin Turk and Madonna not manage to have the last word on Che Guevera mock-ups? And just who or what is Matthew Darbyshire’s living room assemblages of colourful retro furnishings meant to be critiquing? Maybe his budget ran out before he could finish them.

The mood is uplifted somewhat as you step upstairs and find Goshka Macuga’s Madame Blavatsky (pictured bottom right), levitating between two chairs. The founder of the Theosophical Society played a key part in early Modernist painting, seducing Mondrian and Kandinsky with ideas about the spiritual dimensions of colour and line. Modernism was an ideology, after all, not just an aesthetic, just as art today follows the ideology of naked commerce. So a life-sized doll of Blavatsky seems nicely apt. (Perhaps they could do mini versions in the shop.) Macuga is no newcomer either, having been nominated for the Turner Prize in 2008, and you can appreciate a nicely layered sophistication at work here.

Ged Qunn’s paintings are certainly sophisticated, layered, funny and grim. He presents a brilliant amalgamation of the Romantic sublime and the nightmarishly modern in The Ghost of a Mountain, showing Hitler’s mountain retreat, the Berghhof, transported to the forest floor of an imposing Caspar David Friedrich landscape. Such horror as it represents is turned into a Grimm fairytale. And his painting Dad with Tits (main picture) gives the iconic painting of George Washington, now “blacked-up” and with a play on the notion of “founding father”, a further oedipal, gender-bending twist. History, modernity and post-modernity all form part of the mix, as it does in Sigrid Holmwood’s bright fluorescent “genre” paintings of 19th-century peasants.

Ged Qunn’s paintings are certainly sophisticated, layered, funny and grim. He presents a brilliant amalgamation of the Romantic sublime and the nightmarishly modern in The Ghost of a Mountain, showing Hitler’s mountain retreat, the Berghhof, transported to the forest floor of an imposing Caspar David Friedrich landscape. Such horror as it represents is turned into a Grimm fairytale. And his painting Dad with Tits (main picture) gives the iconic painting of George Washington, now “blacked-up” and with a play on the notion of “founding father”, a further oedipal, gender-bending twist. History, modernity and post-modernity all form part of the mix, as it does in Sigrid Holmwood’s bright fluorescent “genre” paintings of 19th-century peasants.This is a big and baggy exhibition, certainly downbeat and ragged and occasionally a bit depressing (in fact, it's a bit like the Royal Academy Summer Show trying to do "edgy"). But there’s also a lot that is clever and layered and sophisticated, which is always a nice surprise at Saatchi HQ.

- Newspeak: British Art Now is at the Saatchi Gallery until 17 October

more Visual arts

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Issy Wood, Study for No, Lafayette Anticipations, Paris review - too close for comfort?

One of Britain's most captivating young artists makes a big splash in Paris

Issy Wood, Study for No, Lafayette Anticipations, Paris review - too close for comfort?

One of Britain's most captivating young artists makes a big splash in Paris

Add comment