Peter Lanyon, Tate St Ives | reviews, news & interviews

Peter Lanyon, Tate St Ives

Peter Lanyon, Tate St Ives

A Cornish master rediscovered. But he should be on show in Tate Britain

A retrospective at Tate St Ives can be a poisoned chalice for the major artist. It postpones his or her prospect of a showing at Tate Britain by a couple of decades, and can appear to consign them to the comfort zone of "Cornish Art": the heritage Modernism of Barbara and Ben, Terry Frost, Patrick Heron et al, stuff we love (well, most of us) because it reminds us of being on holiday, but may feel, in our heart of hearts, to be more than a touch minor. On the positive side, Peter Lanyon, who was killed in a gliding accident in 1964, isn’t around to mind, and there’s something to be said for being able to look from one of his lyrical canvases straight out at the surf crashing on Porthmeor Beach and the edge of the windswept, ancient landscape Lanyon regarded as his personal Calvary.

Of all the artists whose names are irrevocably associated with mid-century St Ives, only Lanyon was Cornish. He considered the others "incomers" (Cornish for interloper), and regarded their preoccupation with Cornwall’s glowing marine light as superficial beside what he, a native, could bring to the table. While Lanyon has remained an iconic figure for painters, as an authentically British pioneer of painterly abstraction, he is little known to the public at large. One of his characteristically blue-and-white, freely painted late canvases will invariably feature in any overview of the 1950s and early 1960s. But this is our first chance in nearly 40 years to ask, how good is Peter Lanyon?

While Lanyon identified with the hardships of the farmers and miners of West Cornwall, he was far from being a horny-handed son of toil himself. Born into a wealthy St Ives family who had made money from tin mining, he received lessons from the traditional marine painter Borlase Smart, linking him to an earlier phase of St Ives art, before he threw in his lot with Hepworth and Nicholson, who gave him lessons in Cubism in Little Parc Owles, a house belonging to the critic Adrian Stokes that Lanyon himself later bought. He considered his principal teacher to be the Russian Constructivist Naum Gabo, who had come to Cornwall under Nicholson’s aegis and used a studio in Lanyon’s father’s garden. All of which shows how tightly Lanyon’s life and career were bound up with the St Ives art world he later professed to despise.

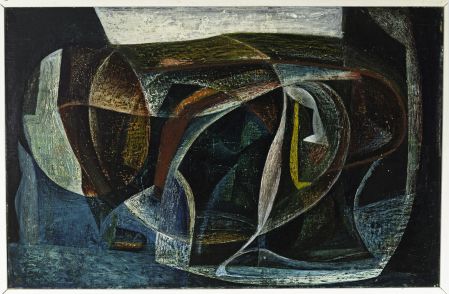

The first objects here are journeyman Modernist constructions from 1939-40, though by the end of the war he had lost faith in Hepworth and Nicholson’s utopian abstraction, and was soon to fall out with them spectacularly. Prelude from 1947 (pictured above) veers towards the then-fashionable Neo-Romanticism of Piper and Sutherland. Abstracted womb-like forms open out beneath a relatively realistic moorland landscape – echoing both mining tunnels and the birth of Lanyon’s first child – the brooding reds and blues given an incised, sculptural quality by the scraping away of wet paint with a razor, a technique learned from Nicholson. Already Lanyon was investing abstracted landscape with a sense of the historic and the personal.

The original version of one of his best-known works, Porthleven, created for the 1951 Festival of Britain, took 14 months to complete. He destroyed it after a spat with Nicholson, and repainted it in four hours. The result is an invigorating gust of a painting, with the clock tower of the fishing village from which it takes its name visible among a mass of swirling marks, as though we're being blown around the village's harbour, and with the figures of a fisherman and waiting woman (harking back to Realist marine painting) just about discernible.

St Just from 1953 (pictured right), another well-known work, named after a mining village near Land’s End, was conceived of as a crucifixion in honour of the Cornish miners from which the figure of Christ had, he said, been "napalmed out" – an echo both of the then-ongoing Korean War and his own sufferings in World War Two. Among a mass of layered graffiti–like marks, derived from the forms of the granite miners’ houses, in greys, blacks and khaki-like greens, the tall painting is dominated by a black forked form that represents both Christ and the mine shaft down which many workers crashed to their deaths. The scratchy, effortful mark-making and melancholy, brutalised near-monochrome feel so much of their time – redolent of European contemporaries like Fautrier and Richier – it’s difficult to judge the painting as an independent work.

St Just from 1953 (pictured right), another well-known work, named after a mining village near Land’s End, was conceived of as a crucifixion in honour of the Cornish miners from which the figure of Christ had, he said, been "napalmed out" – an echo both of the then-ongoing Korean War and his own sufferings in World War Two. Among a mass of layered graffiti–like marks, derived from the forms of the granite miners’ houses, in greys, blacks and khaki-like greens, the tall painting is dominated by a black forked form that represents both Christ and the mine shaft down which many workers crashed to their deaths. The scratchy, effortful mark-making and melancholy, brutalised near-monochrome feel so much of their time – redolent of European contemporaries like Fautrier and Richier – it’s difficult to judge the painting as an independent work.

But the little-seen High Ground is something of a revelation, one of a number of paintings with a palette of turquoise, pale green and lemon, overlain with a scatological smearing of white and black. Inspired by an experience of farm labouring, it strives to capture an experience of action-in-time in two dimensions: a kind of proto-Abstact Expressionism that has nothing to do with New York and quite a lot to do with Italy, which Lanyon saw as his spiritual home.

The overt mythological references of Europa, painted in Italy, feel self-conscious beside the more instinctive and ambiguous relation to myth inherent in his native landscape. While it's interesting to be shown a sculpture related to this painting that has just been unearthed from the artist’s widow’s shed – and his Dadaistic sculptures feature throughout the show – it’s as a painter that Lanyon stands or falls. And in the last couple of rooms his work literally takes off, becoming increasingly ethereal after his discovery of gliding in 1959.

High Wind appears just a mass of random blue and white brush strokes with an obvious but unclear relation to Abstract Expressionism – and though he was friends with Rothko and de Kooning the pattern of influence remains obscure. Lost Mine, relating to a tin mine inundated by the sea, creates a vertiginous feeling of being simultaneously in the mine and looking down on it from a great height, while the layering of blue and white in Thermal (pictured below) gives an exhilarating sense of hanging between atmospheric states.

Lanyon wanted to do a great deal all at once, to invest the hard-fought layering in his paintings with the layering of the personal, the historical and the phenomenological he saw as inherent in the landscape. If there’s the sense of a gap at times between what he wanted to get into the painting and what is actually there, he succeeded in capturing a conjunction of personal and painterly states that no one since has quite emulated, before his glider crashed in a field in Somerset in 1964, ending his life at the age of 46.

This is a beautiful exhibition, full of carefully nuanced echoes between paintings and periods. But it really should be in Tate Britain. Here we’re too close to Lanyon’s landscape and personal world to judge him objectively. He should be viewed against the largest painting of his time, not the tat-filled boutique-galleries of St Ives with their Alfred Wallis coaster sets. Nonetheless, to those convinced of his worth, to see this art so close to its source is a moving, even a powerful experience. If you’re interested in Lanyon, his period or British painting in general, this show is well worth travelling for.

- Peter Lanyon at Tate St Ives until 23 January, 2011

Share this article

Add comment

more Visual arts

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Issy Wood, Study for No, Lafayette Anticipations, Paris review - too close for comfort?

One of Britain's most captivating young artists makes a big splash in Paris

Issy Wood, Study for No, Lafayette Anticipations, Paris review - too close for comfort?

One of Britain's most captivating young artists makes a big splash in Paris

Comments

...