Sally Mann: The Family and the Land, Photographers' Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Sally Mann: The Family and the Land, Photographers' Gallery

Sally Mann: The Family and the Land, Photographers' Gallery

The American photographer's remarkable images beguile, haunt and disturb

Monday, 28 June 2010

Last week I watched a tiny tot being photographed by her father, on a beach in southern Turkey. There was no girlish giggling or splashing about in the sea; rather than a show of carefree happiness, she delivered a studied pose. She assumed an expression of supreme indifference and, with hand on hip and weight on one leg, twisted her body into a seductive coil. The four-year-old was imitating a supermodel! I didn’t see the pictures, of course, but I would still classify this kind of premature sexualisation as child pornography.

The American photographer, Sally Mann was accused of kiddy porn in 1992 when she published Immediate Family, a book of black and white photographs of her three children taken at the family’s summer cabin near their farm in Lexington, Virginia – a remote spot where they could skinny dip in the river and generally run wild. Some of them feature in her exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery and, although she stopped taking them more than 15 years ago, they remain her finest pictures.

A collaboration between mother and child, they celebrate the feral grace of young children who, unlike the acquiescent bathing belle witnessed in Turkey, assert their presence with arrogant aplomb, producing pictures that occupy the opposite pole from pornography. In one shot all three face the camera. Emmett’s pout is unstudied and Jessie’s unsmiling stare uncompromising, and when Virginia rests her hand on her hip, it’s in a gesture of wilful defiance rather than attempted titillation. We are seeing fierce independence rather than compliance – beauty that is unselfconsciousness, dignified and asexual (Pictured right: Candy Cigarette, 1989).

A collaboration between mother and child, they celebrate the feral grace of young children who, unlike the acquiescent bathing belle witnessed in Turkey, assert their presence with arrogant aplomb, producing pictures that occupy the opposite pole from pornography. In one shot all three face the camera. Emmett’s pout is unstudied and Jessie’s unsmiling stare uncompromising, and when Virginia rests her hand on her hip, it’s in a gesture of wilful defiance rather than attempted titillation. We are seeing fierce independence rather than compliance – beauty that is unselfconsciousness, dignified and asexual (Pictured right: Candy Cigarette, 1989).

Mann stopped photographing her children naked when they approached puberty and gradually turned her attention to the landscape around her farm. She also switched from a 10 x 8 view camera to an antique bellows camera and from film to the wet-plate collodion process used by the pioneers of photography in the 1850s. Large glass plates are coated with a silver nitrate solution which has to be exposed and developed while still wet. Its a messy business, especially as insects and dust particles get stuck to the sticky surface and show up on the prints, along with residual signs of handling, as spots, stains, drips and trickles. They give the photographs a painterly patina that is very seductive and can easily become an end in itself.

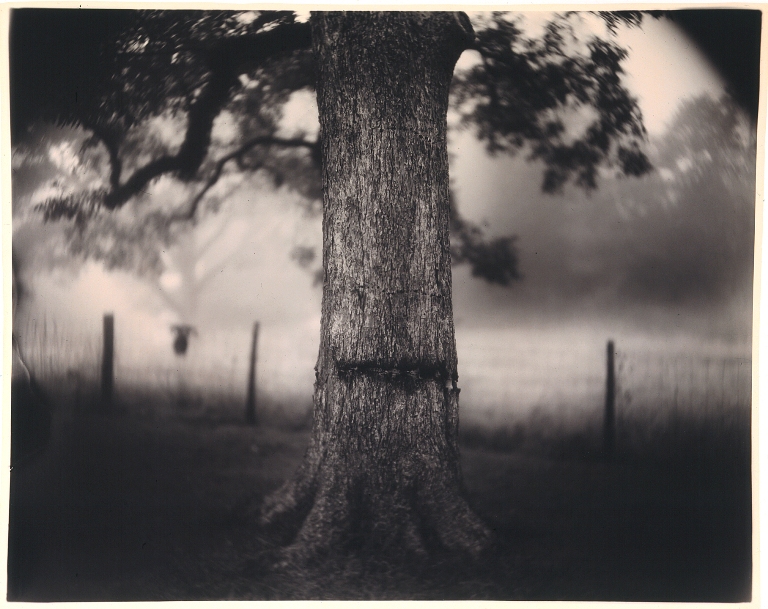

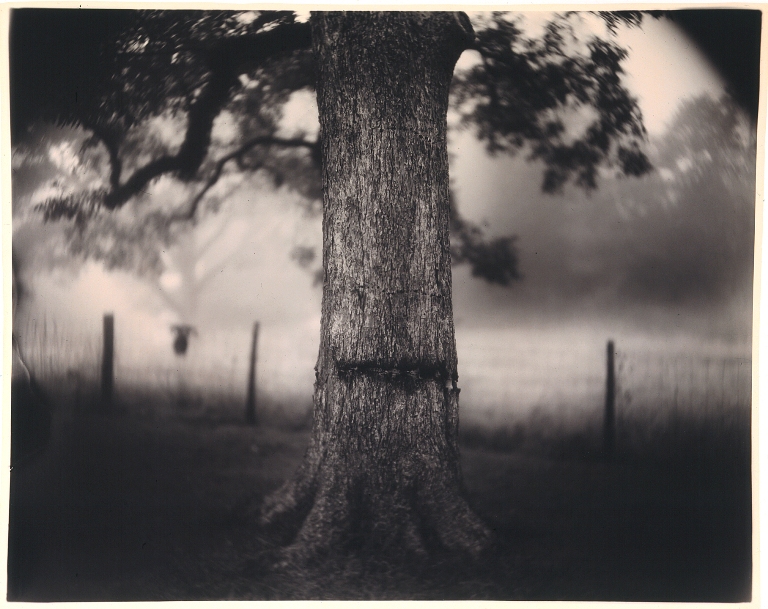

Using her truck as a portable dark room, Mann began photographing civil war battlefields where hundreds of lives were once lost. Deep South (1996-98) would probably have more resonance for Americans than for outsiders like ourselves, for whom the American Civil War is part of someone else’s history rather than a scar on our own national psyche; the intended poignancy of these romantic images therefore passes me by and I also find the anthropomorphism rather heavy-handed. In Swamp Bones, for example, the tangled roots and trunks of mangroves are dimly seen through a miasma of rising damp, like the contorted bones of dead soldiers trapped in a watery grave. The horizontal slash that disfigures the trunk of Scarred Tree, 1996 (pictured above) may resemble a flesh wound seeping blood, but the metaphor still seems over-egged.

Using her truck as a portable dark room, Mann began photographing civil war battlefields where hundreds of lives were once lost. Deep South (1996-98) would probably have more resonance for Americans than for outsiders like ourselves, for whom the American Civil War is part of someone else’s history rather than a scar on our own national psyche; the intended poignancy of these romantic images therefore passes me by and I also find the anthropomorphism rather heavy-handed. In Swamp Bones, for example, the tangled roots and trunks of mangroves are dimly seen through a miasma of rising damp, like the contorted bones of dead soldiers trapped in a watery grave. The horizontal slash that disfigures the trunk of Scarred Tree, 1996 (pictured above) may resemble a flesh wound seeping blood, but the metaphor still seems over-egged.

Next the photographer embarked on a much harder hitting contemplation of the relationship between death and the soil in What Remains (2000- 2004), a series of photographs of dead bodies in various stages of decay, lying in woodland. These are not dead soldiers or murder victims, but corpses left to rot at the Forensic Anthropology Centre of the University of Tennessee, where the process of decomposition is being monitored for scientific purposes.

The pictures exert a grisly fascination. A middle-aged woman lies face down, her ample flesh sagging into the soil like unbaked dough or the misshapen limbs of a rag doll losing its stuffing. The skin on the shoulder of a man is as shiny and pockmarked as lemon peel; the strands of his hair are clearly visible but his face seems to have dissolved into a mush. Haloed in a mane of wispy hair, a grinning skull looms out of the leaves; the skin on the neck and torso resembles pleated cloth, but it is hard to tell whether this is the effect of time on dead cells or of the wet collodion process on glass plates – whether it is the outcome of natural processes or the result of artifice. One could argue that the hand-crafting of these soft-focus shots lends dignity to the dead, but in their horrific beauty, Mann’s subjects are so compelling that, in my view, they don’t need embellishment or poetic licence.

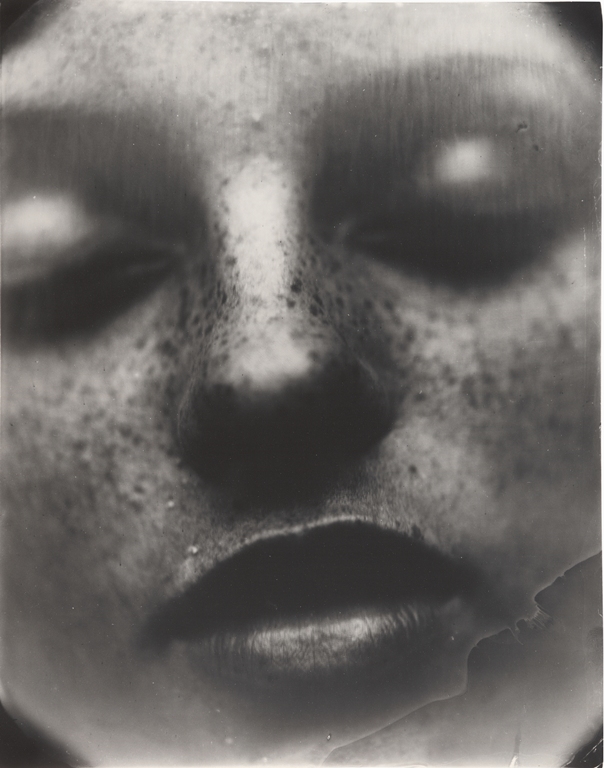

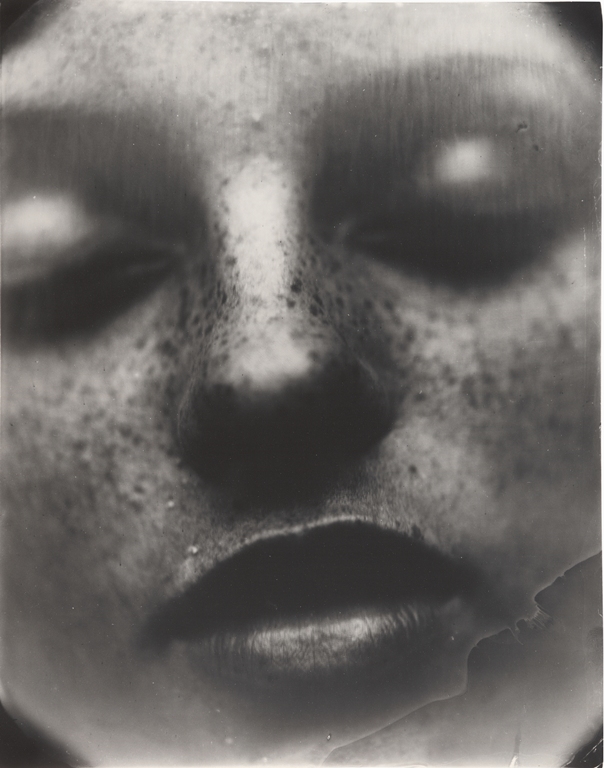

The latest in this ongoing meditation on death is Faces (pictured right: Virginia # 42, 2004), a series of giant portraits of her children who obliged her by lying still and staring into the lens for the five minutes or so required to fix their likenesses onto the glass plates. Enlarged to 3’6” x 4’6” (109 x 137 cms) the resulting close-ups are both monumental and ethereal. Seen through a veil of gestural marks, the faces appear to be surfacing through water – coming slowly into view from the depths, as it were, like a memory gradually taking form.

The latest in this ongoing meditation on death is Faces (pictured right: Virginia # 42, 2004), a series of giant portraits of her children who obliged her by lying still and staring into the lens for the five minutes or so required to fix their likenesses onto the glass plates. Enlarged to 3’6” x 4’6” (109 x 137 cms) the resulting close-ups are both monumental and ethereal. Seen through a veil of gestural marks, the faces appear to be surfacing through water – coming slowly into view from the depths, as it were, like a memory gradually taking form.

Its no exaggeration to say that, in them, Mann has redefined what photography can do. The immediacy normally associated with the photographic image – the sense of a moment captured and frozen for perpetuity in the present tense – is replaced by a feeling of life stilled and time slowed. Rather than being taken (the very word implies an element of theft and, in pressing the shutter after all, one is thwarting time and defying death), these portraits seem to have been created through an act of giving or reciprocity. Perhaps that’s why they seem to memorialise the living, while honouring the inevitability of death. And since they appear hard won rather than effortless and slow rather than instantaneous, they look and work more like drawings than photographs. A remarkable achievement.

This exhibition, which is a very reduced version of a retrospective staged by the Corcoran Gallery Washington, provides the merest glimpse of the work of this important artist; but for a fuller idea of her achievements, Steve Cantor’s 80 minute documentary is well worth watching right through.

A collaboration between mother and child, they celebrate the feral grace of young children who, unlike the acquiescent bathing belle witnessed in Turkey, assert their presence with arrogant aplomb, producing pictures that occupy the opposite pole from pornography. In one shot all three face the camera. Emmett’s pout is unstudied and Jessie’s unsmiling stare uncompromising, and when Virginia rests her hand on her hip, it’s in a gesture of wilful defiance rather than attempted titillation. We are seeing fierce independence rather than compliance – beauty that is unselfconsciousness, dignified and asexual (Pictured right: Candy Cigarette, 1989).

A collaboration between mother and child, they celebrate the feral grace of young children who, unlike the acquiescent bathing belle witnessed in Turkey, assert their presence with arrogant aplomb, producing pictures that occupy the opposite pole from pornography. In one shot all three face the camera. Emmett’s pout is unstudied and Jessie’s unsmiling stare uncompromising, and when Virginia rests her hand on her hip, it’s in a gesture of wilful defiance rather than attempted titillation. We are seeing fierce independence rather than compliance – beauty that is unselfconsciousness, dignified and asexual (Pictured right: Candy Cigarette, 1989).'The young girl’s resemblance to a doll lends the scene the surreal intensity of a horrific dream'

Not all the pictures record halcyon days of sunshine and swimming, though; as though acknowledging the potential dangers that threaten these precious lives, a dark undertow of dread haunts the series. The most disturbing image,The Terrible Picture, shows Virginia apparently hanged from a tree, her eyes closed and body spattered with mud. It is clearly an illusion (the strap doesn’t even go round her neck), yet the picture is utterly compelling as the embodiment of a parental nightmare, and the young girl’s resemblance to a doll lends the scene the surreal intensity of a horrific dream.Mann stopped photographing her children naked when they approached puberty and gradually turned her attention to the landscape around her farm. She also switched from a 10 x 8 view camera to an antique bellows camera and from film to the wet-plate collodion process used by the pioneers of photography in the 1850s. Large glass plates are coated with a silver nitrate solution which has to be exposed and developed while still wet. Its a messy business, especially as insects and dust particles get stuck to the sticky surface and show up on the prints, along with residual signs of handling, as spots, stains, drips and trickles. They give the photographs a painterly patina that is very seductive and can easily become an end in itself.

Using her truck as a portable dark room, Mann began photographing civil war battlefields where hundreds of lives were once lost. Deep South (1996-98) would probably have more resonance for Americans than for outsiders like ourselves, for whom the American Civil War is part of someone else’s history rather than a scar on our own national psyche; the intended poignancy of these romantic images therefore passes me by and I also find the anthropomorphism rather heavy-handed. In Swamp Bones, for example, the tangled roots and trunks of mangroves are dimly seen through a miasma of rising damp, like the contorted bones of dead soldiers trapped in a watery grave. The horizontal slash that disfigures the trunk of Scarred Tree, 1996 (pictured above) may resemble a flesh wound seeping blood, but the metaphor still seems over-egged.

Using her truck as a portable dark room, Mann began photographing civil war battlefields where hundreds of lives were once lost. Deep South (1996-98) would probably have more resonance for Americans than for outsiders like ourselves, for whom the American Civil War is part of someone else’s history rather than a scar on our own national psyche; the intended poignancy of these romantic images therefore passes me by and I also find the anthropomorphism rather heavy-handed. In Swamp Bones, for example, the tangled roots and trunks of mangroves are dimly seen through a miasma of rising damp, like the contorted bones of dead soldiers trapped in a watery grave. The horizontal slash that disfigures the trunk of Scarred Tree, 1996 (pictured above) may resemble a flesh wound seeping blood, but the metaphor still seems over-egged.Next the photographer embarked on a much harder hitting contemplation of the relationship between death and the soil in What Remains (2000- 2004), a series of photographs of dead bodies in various stages of decay, lying in woodland. These are not dead soldiers or murder victims, but corpses left to rot at the Forensic Anthropology Centre of the University of Tennessee, where the process of decomposition is being monitored for scientific purposes.

The pictures exert a grisly fascination. A middle-aged woman lies face down, her ample flesh sagging into the soil like unbaked dough or the misshapen limbs of a rag doll losing its stuffing. The skin on the shoulder of a man is as shiny and pockmarked as lemon peel; the strands of his hair are clearly visible but his face seems to have dissolved into a mush. Haloed in a mane of wispy hair, a grinning skull looms out of the leaves; the skin on the neck and torso resembles pleated cloth, but it is hard to tell whether this is the effect of time on dead cells or of the wet collodion process on glass plates – whether it is the outcome of natural processes or the result of artifice. One could argue that the hand-crafting of these soft-focus shots lends dignity to the dead, but in their horrific beauty, Mann’s subjects are so compelling that, in my view, they don’t need embellishment or poetic licence.

The latest in this ongoing meditation on death is Faces (pictured right: Virginia # 42, 2004), a series of giant portraits of her children who obliged her by lying still and staring into the lens for the five minutes or so required to fix their likenesses onto the glass plates. Enlarged to 3’6” x 4’6” (109 x 137 cms) the resulting close-ups are both monumental and ethereal. Seen through a veil of gestural marks, the faces appear to be surfacing through water – coming slowly into view from the depths, as it were, like a memory gradually taking form.

The latest in this ongoing meditation on death is Faces (pictured right: Virginia # 42, 2004), a series of giant portraits of her children who obliged her by lying still and staring into the lens for the five minutes or so required to fix their likenesses onto the glass plates. Enlarged to 3’6” x 4’6” (109 x 137 cms) the resulting close-ups are both monumental and ethereal. Seen through a veil of gestural marks, the faces appear to be surfacing through water – coming slowly into view from the depths, as it were, like a memory gradually taking form.Its no exaggeration to say that, in them, Mann has redefined what photography can do. The immediacy normally associated with the photographic image – the sense of a moment captured and frozen for perpetuity in the present tense – is replaced by a feeling of life stilled and time slowed. Rather than being taken (the very word implies an element of theft and, in pressing the shutter after all, one is thwarting time and defying death), these portraits seem to have been created through an act of giving or reciprocity. Perhaps that’s why they seem to memorialise the living, while honouring the inevitability of death. And since they appear hard won rather than effortless and slow rather than instantaneous, they look and work more like drawings than photographs. A remarkable achievement.

This exhibition, which is a very reduced version of a retrospective staged by the Corcoran Gallery Washington, provides the merest glimpse of the work of this important artist; but for a fuller idea of her achievements, Steve Cantor’s 80 minute documentary is well worth watching right through.

- Sally Mann: The Family and the Land at the Photographers' Gallery until 19 September

more Visual arts

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Add comment