theartsdesk Q&A: Artist Douglas Gordon | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Artist Douglas Gordon

theartsdesk Q&A: Artist Douglas Gordon

The Glaswegian artist explains how the city made him

24 Hour Psycho plays the entirety of Hitchcock's classic on a pair of screens, but reduced to two frames a second. First mounted at the Tramway in 1993, the work established Gordon as an ambitious and questioning manipulator of video installation, still a new medium.

Gordon's work has since been exhibited in MoMA, the National Galleries of Scotland, the Venice Biennale and the Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin. In 2006 he was in the vanguard of a new trend in visual art. He gained access to an exhibition space subsequently visited by other gallery artists: the cinema screen. Shot with French artist and director Philippe Parreno, his film Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait was the fruit of a collaboration with the most charismatic sportsman of the age, Zinedine Zidane. It is not necessarily faint praise that this obsessive, hypnotic work may well be the best football film ever made.

Gordon now lives in Berlin, where he spoke to theartsdesk over lunch about the long shadow cast by Glasgow, and the home he has turned into a gallery.

Both pictures from 24 Hour Psycho Back and Forth and To and Fro', 2008. Video installation with two screens and two projections. 24 Hour loop. (Image courtesy of the artist. From Psycho. 1960 USA. Directed and produced by Alfred Hitchcock. Distributed by Paramount Pictures © Universal Studios, Inc.)

JASPER REES: As there’s another World Cup coming, let’s start with your most seen work. You live in Berlin, but is France a home from home for you as an artist?

DOUGLAS GORDON: There’s probably more work of mine in France than anywhere else. The French institutions supported me from very early on. All these Frac organisations and then the Centre Pompidou and then the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. And then I spent the good part of a year in a hotel when I was editing the Zidane film. And that was rushing. We could have probably done with another three months, but we had to get it out in time for Cannes.

How thrilled were you when, at the end of the match you filmed him in, Zidane got sent off?

We were genuinely concerned for him. We didn’t hang out with him a lot but we felt very close to him. And we knew that he was trying to do his very best and I think the frustration just boiled over. Having said that, we also knew that he’s got that hot head. He’s been sent off more than anyone else in that position at Real Madrid. The long walk to Calvary. There was a lot of metaphors flying around. If it had happened on the centre circle it would have been a short walk. As it was, it couldn’t have been orchestrated better. He went to the faraway corner flag and had pretty much the whole pitch to walk to get off.

Did you understand why he headbutted the Italian defender in the World Cup final in 2006?

I was absolutely devastated. I was here. I went to the game. I actually sat at this table when I got my ticket. I was still living in New York. We had already opened in Cannes and we’d had some arguments with Universal who were doing the distribution. We didn’t want to open in Cannes. We wanted to wait. We thought France would get to the final and release the film on the day. It was a risk.

Watch a clip from Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait on YouTube

Last year you took part in Inspired, an exhibition in Glasgow celebrating the life and work of Robert Burns. Were you happy to take part in a group show?

It’s very difficult for people to reach me and that’s not always my fault. But there’s been a wee bit of a mythology grown up around how difficult it is to reach me and it comes in handy. I think the organisers maybe thought I was still living in New York, but I had already left. So the organisers had to try to get to a gallery, the gallery has to get to my assistant, one of my assistants has to track me down. I was well aware that Burns was going to be celebrated in many different ways and I was quite happy to burn something up.

You could have said no.

That would probably have seemed a little bit snobbish. I know some of the Scottish artists in the show and if it was good enough for them then it would be fine for me.

When did you get the invitation?

I might have been in the Caribbean when I got it. I tried to decompress a bit when I was leaving New York before I came back to Europe. I was in the Caribbean a lot. I think I was trying to organise a Burns supper actually. Very, very difficult to get haggis. I think we actually ended up having to modify it and go for a fish.

Burns Night at the very least means something to you then?

I think it’s the most important night of the year. Since I was brought up not celebrating birthdays, Christmas or New Year very much, not only did Burns Night seem less bogus, one of the great things about going to the Art School in Glasgow was this really pretty radical attitude to public performance. I used to do very slow and boring performance art but by night you had to be able to sing at least three ballads if you wanted to go out with your tutors and your pals. I think probably the most important thing I took away from art school was not to learn how to sing but to learn to be able to sing. Most of the people I graduated with either can play an instrument or are in a band or can sing about 20 or 30 songs.

That was entirely down to Burns Night?

For me it was more the traditional music thing. From people like Jim Lambie or all the guys in Franz Ferdinand, all the guys in Travis, they’re all coming from the Art School. So they would be a bit more hip than me singing “My Love Is Like a Red, Red Rose”. Or maybe not.

Does his cultural influence extend beyond 25 January?

When I was a child or a student up in Scotland what was seen to be important to us about Robert Burns is that he wasn’t just a local boy done good, it was that he was international. And the mythology that I grew up with was that more people in Russia knew how to sing "My Love Is Like a Red, Red Rose" than people in Scotland and that there were Burns Nights in Africa and people celebrated him in South America. He really represented something international as opposed to parochial. That was the prevailing thing for me.

To put it crudely, he put Scotland on the map.

He had a global currency as opposed to a local one.

Was that something that was apparent to you in relation to Scotland’s relationship with England? That is, was it a way of separating Scotland from the Saxons?

No, not at all. With Burns I don’t think there is an anti-English sentiment. He’s a tits-and-arse man. He’s so focused on that he had very little time for what used to be the traditional Scottish-English rivalry. I don’t recall any of that in the work. Tits, arse and haggis.

Was he identifiably an Ayrshire man?

I spent a long period of years going to visit people in Ayrshire because I had a relationship with somebody there. And then people who have been influential even from my generation, like Andy O’Hagan, who is a great friend of [Graham] Fagen – they were all Irving-based guys, and then I had cousins in Ayrshire. So there is a certain Ayrshire mentality. These days it may not be as extreme as it was. In Burns’s time the sophistications of Edinburgh hadn’t got quite as far as the farmer’s field and the industrial wasteland of Glasgow hadn’t been penetrated by them. I always loved my time in Ayrshire. It’s strangely local and international at the same time. I was always struck by how they are very hardy people. And it’s the seat of freemasonry as well. There’s a lot going on in Ayrshire.

When did you last live in Glasgow?

I still have a place there. I left New York in September 2007 and I got stranded a little bit in the Caribbean and really I intended to go back and live in my place in Glasgow; en route I went to Manchester to do this artist opera and fell in love with somebody there who lived here. I was distracted. I still have my place in Glasgow and I go back as often as I can. But there is a sense of going back and not being there. But I practise my accent every day.

It surely doesn’t require it.

You can imagine the laughs if you go into the bar in Glasgow. I quite often go to the Viceroy bar, which is near Ibrox, although I’m not a Rangers supporter. If you go in there and you say, “I got stuck in an elevator the other day” and “Did you see all that shit on the sidewalk?” people are just pissing themselves laughing. That was just the New York experience and now when I’m here I speak German as much as possible and verbs are ending up at the end of sentences with a Glaswegian accent in English when you’re back in Scotland. I like to think I make some people happy through that.

What is unique about Glasgow that has produced so many successful contemporary artists? If you measure these things in Turner Prize victories and nominations it’s a very high strike rate.

There’s only two Scottish people that actually won it. Maybe in years to come it’ll be one of those things like the Celtic football team who all came from a 14-mile radius. I don’t think there’s a smart answer for any of it. My personal experience is that we were very very lucky at the time we went to the Art School. The Art School had a particularly structured chaos at that time. I went from ’84 to ’88. The miners’ strike had just about come to a close. At least there was some political meat on the table rather than the situation now. The meat is still there, it’s just hidden very carefully under the table. There was a political awareness for people at student level, people were motivated to do something about their politics. And there were the old staff who would disappear to the Arts Club for lunch and not come back, or come back not sober. And then there were the younger generation who took their teaching seriously in a different way. So we got a pretty good mix of the old alcoholics with their oil paints and then this younger breed coming who would as quickly throw a book at you as the book at you. It might be Derrida or Baudrillard or whatever.

In our situation in particular with Christine Borland and Roddy Buchanan we were in a department that used to be called the murals and stained glass department, and then it changed to the environmental art department. And we just happened to fall in between. There’s two or three years of people who really benefited from the fact that the door was neither open or closed. It was kind a revolving-door situation. It was great.

In what way did you benefit?

This is the great thing for me at Art School. You’d be in there drawing an emaciated life model. And I remember Graham Fagen signalling over to me, “Forget it, forget it, the Clash have just arrived in Glasgow. They’re playing an acoustic set down at the Rock Garden. Let’s go.” And you could just very quietly drop your charcoal on the ground and then run away from Art School and go and watch Joe and the boys. So it was very strict and lax.

Dropping your charcoal and leaving the life class is kind of symbolic, isn’t it?

That beautiful noise.

And you never really went back.

I don’t think I did go back actually.

Is there something specifically Glaswegian about that aura of creative chaos married to political engagement?

No, I’m pretty sure it was very active, certainly in London. When I went to the Slade to do my postgraduate stuff it was a bit of an eye-opener to meet people who had been at art school in Leeds and then you’d hear about the legacy of Newcastle Poly when Richard Hamilton was there. And Hornsey College of London. I suppose by the time I knew what was happening it was all over. But that’s fine as well. We were just encouraged to get out and about and mix it up a bit. Somebody who had as big an influence on me as Robert Burns would be Alasdair Gray. I remember when I left Glasgow to go to London I read a short story that he wrote called The Rise and Fall of Kelvin Walker. It was about a Scotsman on the make in London. Hilarious and very true. It wasn’t at all any reflection on my situation.

What was it about his writing? Was it his irreverence and anarchy?

I think there’s a lot of similarity between Gray and Burns. There’s a lot of very lascivious, bordering-on-pornographic obsession which is I think very healthy. These passions are better kept alive than condemned to death. One of the things we have to be careful of is that his philosophy has turned into catchphrase. To see ourselves as others see us, there is something very noble in that. And I think Alasdair Gray absolutely had that, even though a lot of the seeing ourselves as others see us might be done through complete fantasy, or phantasm even. Gray for me also exemplifies somebody who, although – I don’t think Alasdair ever left Scotland but the same as Burns, they were already looking further afield than the field.

How about the other art forms in Glasgow? It’s as basic as that quotation from Gregory’s Girl, my second favourite Scottish film.

Ah I knew you were a Braveheart fan.

Local Hero, please.

I think the best Scottish film is The Sweet Smell of Success. Alexander MacKendrick. Although it’s set in New York the dialogue is like a bad night in Glasgow.

Anyway, there are the two ugly guys who can’t get a girl and watch Gregory being escorted around by a variety of girls. One of the boys says, "There’s definitely something in the air tonight." Was there something in the air, with the music, design, fashion, art all very vibrant?

The particular department that I went into was like the Battersea Dogs’ Home of the Glasgow School of Art. It was all the mongrels would go there. I like everybody else wanted to go into the painting department but the painting department didn’t want me and then I wanted to go into sculpture but sculpture didn’t want me. And so I ended up in this new department which didn’t really have a philosophy, didn’t really have a history, which was the best thing for me.

By accident you turned up in the right place.

Yup. And I’ve been lucky enough that that’s happened so far most of my life. I walked in this bar by accident 12 or 13 years ago, because after I’d won the Turner Prize I got another prize which brought me here and of course you work very, very, very hard to get where you are but I like the idea of either luck or divine intervention, and I can’t cope with divine intervention. There’s a whole list of names of people who went into that environmental department. At the Art School at that time you either bumped in Alan Horne or you knew somebody who knew Bobby Gillespie or you knew somebody who was in Jesus and Mary Chain. Everybody was either in a band or related to someone or lent a guitar to somebody. And for somebody like me, who at that time was too shy to be doing anything like that, I thought, if they’re all doing this, I have to work very hard to stick to what I’m doing. But also get out there.

To compete?

Yup. As a Partick Thistle fan you have to try and find success somewhere else in life.

So there was an element of competition but everyone was stimulating everyone else.

Aye, and helping each other all the time. I was doing performance art in the Eighties and was very lucky somebody couldn’t do something somewhere so I got invited to go there with my friend Craig Richardson. We filled in and it was successful. It was like a music story of the support band getting lost and someone else having to jump up on stage. So I was lucky when I went to this performance festival in Holland, I met some students from the Slade and they were like, “Why don’t you apply here?” And I had honestly never thought of the possibility of moving outside of Scotland to study. But I applied and go in and went down and a conspiracy of circumstances propelled me. I do remember actually a teacher of mine giving me on the one hand a big guilt thing about leaving and then giving me a hug and saying, "But you’ll always come back."

Have some people expressed dismay or worse? Has the word Judas been used?

After winning the Turner Prize it was pretty hellish, I have to say. There was a lot of backbiting, backstabbing, penny-pinching. That was just London. It got worse when I got back to Glasgow. Again I was lucky because as soon as I got the Turner Prize I left. I went to live in Hanover where I had a prize, I came to live here and then I went to Cologne. There was a really nice domino effect.

How about the fashion?

If you were a boy at art school you would want to hang out with all the textiles people because that’s where all the girls were. I mean I only just recently met Pam Hogg which for me was absolutely fantastic. I didn’t realise that she’s related to James Hogg. The Confessions of a Justified Sinner is more or less my bible. I want to make a feature of it. I said to Pam, “Well, why don’t you do the costumes for us?” If you were from Glasgow and you were lucky enough to travel and anyone said to you when you were working abroad, “What do you think of so and so?” no matter what you thought of so and so you always say, “One of my best friends, they’re fantastic. You should come to Glasgow and see them.” So anybody who would be speculatively interested in what was going on in Glasgow, it was an unwritten rule that you don’t shit on your own doorstep.

So internal competition but also mutual support.

Just the way it should be on any football team.

Is there something about the Glaswegian character, most famously exported in the person of Billy Connolly, which has a kind of irreducible creative gene?

I think you’d have to ask King Billy. There’s something great about the fact that Catholic kids can be called Billy in Glasgow and Protestant kids can be called Peter or Paul. You have to be pretty determined to survive. I don’t like that kind of philosophy that Glasgow is the best place in the world. I’ve had the best times of my life in Glasgow. I’ve had the worst of times as well. The bitterness and cynicism is absolutely shocking.

Isn’t that part of the overarching personality?

I think it’s probably underarching.

But there’s something about the presiding character that is quite coarse-grained.

I think Alex Ferguson would sum that up actually. Alex Ferguson I don’t think is particularly popular in Glasgow partly because he represents what the place is about: a highly driven, incredibly successful guy who still doesn’t seem to have a smile on his face.

It’s the George Robertson mouth: tight and ungiving.

My daughter has that actually. “Where’s that noise coming from? You don’t have a mouth!”

Were there any particular galleries or museums that loomed large in your early career?

When I left London, when I went back up to work at Transmission 20 years ago, it was the most important gallery. Transmission Gallery perhaps even more than the Art School allowed people the freedom and the force of this spirit of self-determination and self-help, that you didn’t necessarily have to have Charles Saatchi come knocking on your door in order to be exhibiting or make a living. Making a living came a lot later, obviously. But those were the days when you could still be on the dole. I think Transmission encourages a lot of people to get off their arse and do other things as well. I remember we had to sit through meetings every year with the Scottish Arts Council and the Glasgow City Council. The Scottish Arts Council meetings were quite tough because they really wanted to take the high road to high capitalism. Glasgow City Council were fantastic. They used to come and basically see that everything was clean and tidyish but not too tidy. They had a fantastic laissez-faire attitude. At least until the late Nineties they were amazing.

How about the big city museums?

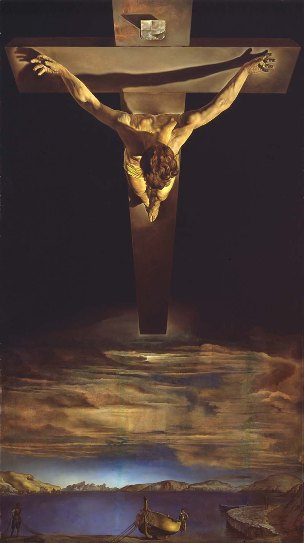

For different reasons. My family were from Maryhill in the north of the city and I’m sure this is a rose-tinted memory of my childhood, but my memory is that I used to go to the Kelvingrove Museum every week. We started off in the musty downstairs with this terrifying tyrannosaurus rex and knights in shining armour and all these species of birds in one box that if they’d actually been alive they’d have pecked each other to death: a fantastic Hitchcockian scenario. And then as I got older you’d slowly start to gravitate upstairs. There was obviously a practicality thing. A stuffed elephant has to be downstairs and the Salvador Dalí has to be upstairs because of the weight. But I felt there was this fantastic Victorian municipal or provincial attitude that kids start downstairs and then when you’re old enough to walk you can go upstairs.

I was 12, coming from Maryhill, though by that time my family were in Dumbarton. But you could go to the Kelvingrove Museum and see a small cast of a rodent and Toulouse-Lautrec and Rodin and the famous Salvador Dalí painting of St John on the cross (pictured right: Christ of St John of the Cross, Kelvingrove Museum). All of that, and reading where Dalí was from and Rodin was from - that pushed me to get a job in a supermarket to save up money to get on a train, go from Glasgow to London, went to the Tate Gallery when I was 17, blew my mind, then went to the ferry and went to Paris. I was 16 or 17. Say 12, it sounds much better.

I was 12, coming from Maryhill, though by that time my family were in Dumbarton. But you could go to the Kelvingrove Museum and see a small cast of a rodent and Toulouse-Lautrec and Rodin and the famous Salvador Dalí painting of St John on the cross (pictured right: Christ of St John of the Cross, Kelvingrove Museum). All of that, and reading where Dalí was from and Rodin was from - that pushed me to get a job in a supermarket to save up money to get on a train, go from Glasgow to London, went to the Tate Gallery when I was 17, blew my mind, then went to the ferry and went to Paris. I was 16 or 17. Say 12, it sounds much better.

I really thought, if I’m going to make anything in this career or at least have a good time, I need to get on a train. This was before the Burrell Collection and all that. The collection in Glasgow City Art Galleries at that time was absolutely fantastic. During the Julian Spalding years [director of Glasgow Museums and Art Galleries, 1989-1998], let’s just say he had other priorities. Actually at one point Jonathan Monk and I went and saw an Andy Warhol soup can that was particularly badly placed and installed and thought, we should just steal this and give it back when they know what to do with it.

Do you go to the Gallery of Modern Art?

I’ve been in once. I went once to see Jim Lambie’s show. I think it’s unfortunate that Julian Spalding had a pretty poisonous relationship… he doesn’t have a relationship with me. If he came in and sat down I’d be perfectly happy to have a glass of wine. He’s gone on record and made some pretty horrendous remarks about not only me and my practice but my peer group and I just don’t understand how anybody who is supposed to be a public servant has got the time to attack anyone, who at that time was not in the collection.

The most important gallery in Glasgow is in my house. Years and years ago I was lucky – this is probably around Turner Prize time, a bit after that – to have some money. I got a place just above the park - very, very close to the Kelvingrove Museum. So basically from my bedroom window I can look at the place I went to every weekend with my mum and dad, and I’ve taken my son there and I’ll take my daughter there. It’s a fantastic place. But I bought this house and then moved away from Glasgow very quickly but kept the house. Then when I thought I was going to be leaving New York to come back to Glasgow; I started to renovate it a bit because the weather was taking its toll.

A friend of mine, Katrina Brown, runs The Common Guild, which is based on a William Morris idea of spreading the good for the wealth of the people kind of thing. Katrina and I used to share a house in Hill Street in Glasgow for years, became great friends and we’re still in touch. I had decided to come back to Glasgow and I renovated the house. It’s a three-and-a-half-storey Georgian townhouse. It’s really quite beautiful. And then I met my girlfriend in Manchester and thought, I’ll probably be in Berlin. So Katrina and I had a meeting in Glasgow and then we went to Glasgow’s premier gay nightclub, called Bennetts. “Premier” because there’s only one. We used to go there when we were at Art School. We were on the dance floor dancing to Erasure and I was like, “So, do you have a place for your shows?” And she’s like, “Uh uh.” I said, “Use mine, use mine.” And she’s like, “OK.” That was how the deal was done.

It opened in 2008. It’s well funded by the City Council. It’s 221 Woodlands Terrace. The space is beautiful for art to be seen in, so why should it be closed? And if I’m not there very much I wanted to put a bit back into the community. I really did. I hate to say these things. My girlfriend would say it’s Polish-Jewish guilt but I’m not Polish or Jewish. I know how much I benefited from the enthusiasm and generosity of my teachers and it goes right back to primary school. I could identify by name the people. I basically got bounced – in a positive way – from a teacher that I had in primary 5 who wrote something on the report card that encouraged my mum and dad to encourage me at art. That got me to meet two fantastic teachers at secondary school, and then when I got into art school it wasn’t always easy but my teachers were more than generous. And not only that, if you were travelling around the world, they all knew someone somewhere and you’d no qualms about phoning someone up and saying, “Hello, I’m in Dublin, you’re a friend of my teacher's, can I stay with you tonight?” I’m not saying that everybody should get on a plane and come and see me in Berlin.

But you’re not easy to get hold of anyway, you claim.

Exactly. I’ve moved three times in a year in Berlin.

When you made this eccentric arrangement, how soon after that was the first show?

I think we went to Bennetts in July and opened six or seven months after that. I had to renovate. The opening show had one or two pieces from Roni Horn, an amazing piece from my favourite Welsh artist of all time, Cerith Wyn-Evans. I think he’s one of the most important living Welshmen, apart from the rugby team. It’s a non-profit space, which is important. I have this beautiful space which is really great for looking at certain types of art. Also having lived in New York for six or seven years and seeing the way that galleries had becomes more sterile than museums, Katrina and I were thinking there are certain works that artists make that really don’t look good in museums. The scale or the flavour of them can be much better experienced in a domestic setting.

One of the reasons why I love Berlin and feel very comfortable here is I feel it’s very like Glasgow. In a couple of emails when I wrote to people to say where I was I just used to say, “I’m living in this great place called Bergow. It’s somewhere between Berlin and Glasgow.” There’s something here that if it wasn’t supported officially it would happen anyway. I don’t want to sound like I’m in a way Thatcherite but there is a thing like that from Glasgow. If it can be officially supported that’s really where the heart of the city should beat, but if it wasn’t supported officially it would happen anyway because people do tend to get off their arse and do things.

Can you imagine going back to live there one day?

Yeah, definitely. Since I had a child born in New York and a child born in Berlin, it might be nice if I had one born in Glasgow.

Share this article

more Visual arts

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Add comment