Naum Kleiman: Eisenstein on Paper review - a lavish journey into the unconscious | reviews, news & interviews

Naum Kleiman: Eisenstein on Paper review - a lavish journey into the unconscious

Naum Kleiman: Eisenstein on Paper review - a lavish journey into the unconscious

Another world to be found in the master film-maker's fantasy sketches

"From drawing, via the theatre, to the cinema". Naum Kleiman's introductory qualification of Sergey Eisenstein's own self-perceived line in his Film Form is one that he follows in a necessarily selective and well-organised biography of the director as graphic artist, acompanied by over 500 previously unpublished illustrations.

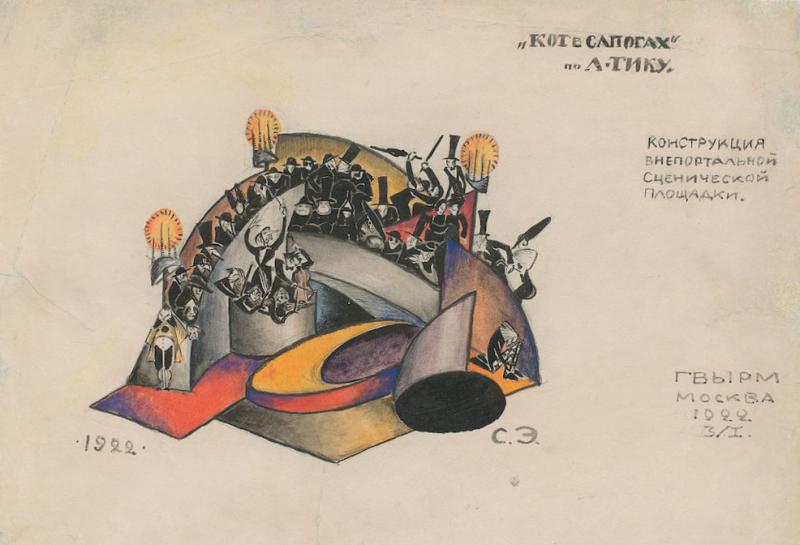

We follow the phenomenon from the young fantasist of Riga, anthropomorphising creatures as society eccentrics, though stage designs indebted to Meyerhold's example - what one wouldn't give to see realisations of his sets and costumes for Shaw's Heartbreak House and Offenbach's The Tales of Hoffmann - and on to the revealing sketches for Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible, with a coda outlining Eisenstein's leaning towards choreography on the eve of his untimely death on 11 February 1948, less than a month after his 50th birthday.

But there's so much between the lines that defies categorisation - those flowing, Matisse-like reductions of form which the master described as "emotional hieroglyphs of pre-cognition". He knew that often these were far from the work of a master draughtsman; rather they were like the offspring "of a fruit fly, that reproduces 12 times a year (?)"; they are "impulsive, sensuous, instinctive," complementing the conscious mastery of the finished cinematic masterpieces.

But there's so much between the lines that defies categorisation - those flowing, Matisse-like reductions of form which the master described as "emotional hieroglyphs of pre-cognition". He knew that often these were far from the work of a master draughtsman; rather they were like the offspring "of a fruit fly, that reproduces 12 times a year (?)"; they are "impulsive, sensuous, instinctive," complementing the conscious mastery of the finished cinematic masterpieces.

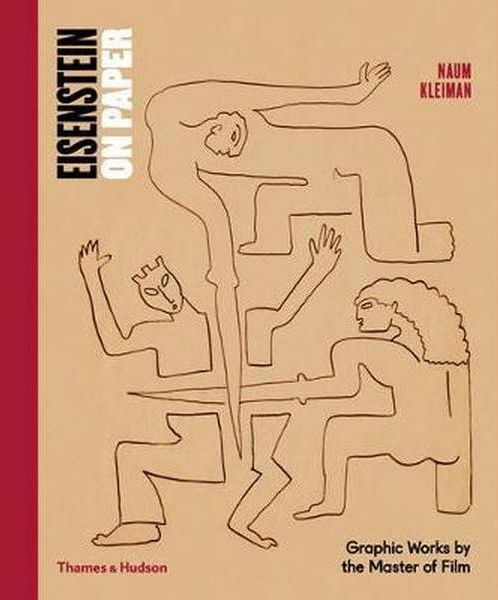

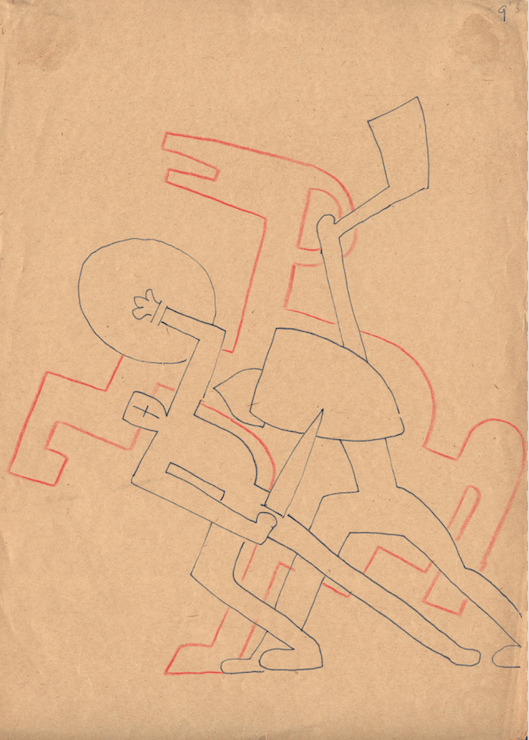

The subjects are telling - religious, mythological, selectively dramatic (why the obsession with Macbeth's murder of King Duncan, one wonders, looking at one of the finest series reproduced here - one seen on the front cover pictured above?) And as well as the film sketches - none, incidentally, for the silent masterpieces, which means a gap of eight years in the visual biography - there are side-works. Eisenstein's regular use of telling red lines visualises the musical dimension in the Moscow decade, revelatory in a sequence devoted to Alexander Nevsky's Battle on the Ice, where we "see" the impact of Prokofiev's music in his colleague's pencil artistic strokes (an example pictured below).

Curiously the only element missing here is the phallocentric, probably because a selection of Eisenstein's erotic drawings has already appeared in print (as Dessins Secrets). There's not an erect penis in sight, and Kleiman rather glides over the issue of homoeroticism in the allegedly bisexual Eisenstein's work (though not his identification with "man, woman and child" represented in single figures). Even so, it is up to us to make what we will of that final, numinous appearance of the Diaghilev/Debussy/Nijinsky Faun transfigured in the "Afterword".

Curiously the only element missing here is the phallocentric, probably because a selection of Eisenstein's erotic drawings has already appeared in print (as Dessins Secrets). There's not an erect penis in sight, and Kleiman rather glides over the issue of homoeroticism in the allegedly bisexual Eisenstein's work (though not his identification with "man, woman and child" represented in single figures). Even so, it is up to us to make what we will of that final, numinous appearance of the Diaghilev/Debussy/Nijinsky Faun transfigured in the "Afterword".

Kleiman has his own theories on its significance, which get a bit out of hand at the end. Still, better that than no sense of style, and no matter when it comes to the look of the thing. Beautifully produced, with admirable support from the perfectionist Kino Klassika foundation which brought us one of the live highlights of the year, October accompanied by an imaginative reconstruction of Edmund Meisel's original score, this is a work of art in itself to set alongside Eisenstein's major achievements.

- Naum Kleiman: Eisenstein on Paper: Graphic Works by the Master of Film (Thames and Hudson, £60)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Shon Faye: Love in Exile review - the greatest feeling

Love comes under the microscope in this heartfelt analysis of the personal and political

Shon Faye: Love in Exile review - the greatest feeling

Love comes under the microscope in this heartfelt analysis of the personal and political

Philip Marsden: Under a Metal Sky review - rock and awe

Myths, mines, and mankind combine in this wide-eyed reading of the earth beneath our feet

Philip Marsden: Under a Metal Sky review - rock and awe

Myths, mines, and mankind combine in this wide-eyed reading of the earth beneath our feet

Jacqueline Feldman: Precarious Lease review - living on the edge

The trials and triumphs of a city’s margins are observed by an outside eye

Jacqueline Feldman: Precarious Lease review - living on the edge

The trials and triumphs of a city’s margins are observed by an outside eye

Catherine Airey: Confessions review - the crossroads we bear

Family trauma repeats in this deftly strange exploration of roads not taken

Catherine Airey: Confessions review - the crossroads we bear

Family trauma repeats in this deftly strange exploration of roads not taken

Best of 2024: Books

As 2024 comes to an end, we look back at the books that have thrilled and enthralled us

Best of 2024: Books

As 2024 comes to an end, we look back at the books that have thrilled and enthralled us

William J. Mann: Bogie & Bacall review - beyond the screen

Why we're still in love with Bogart and Bacall, and their legendary Hollywood romance

William J. Mann: Bogie & Bacall review - beyond the screen

Why we're still in love with Bogart and Bacall, and their legendary Hollywood romance

Add comment