Arvo Pärt Special 2: 'If you want to understand my music read this' | reviews, news & interviews

Arvo Pärt Special 2: 'If you want to understand my music read this'

Arvo Pärt Special 2: 'If you want to understand my music read this'

Tintinnabuli and other mysteries explained

My first encounter with Arvo Pärt’s music is indelibly etched on my consciousness. My piano teacher – the late Susan Bradshaw – placed a piece in front of me which, from a visual point of view alone, was immediately intriguing. Consisting of just two pages, what was most striking about the music was its utter simplicity: there was no time signature; no changes of tempo, key or dynamics; no textural variation.

This was 25 years ago when I was an undergraduate at Goldsmiths, University of London. Pärt at that time was virtually unknown in the West. Since then, he has become one of the most widely performed, recorded and fêted contemporary composers, one of a select few who make their living solely through composition.

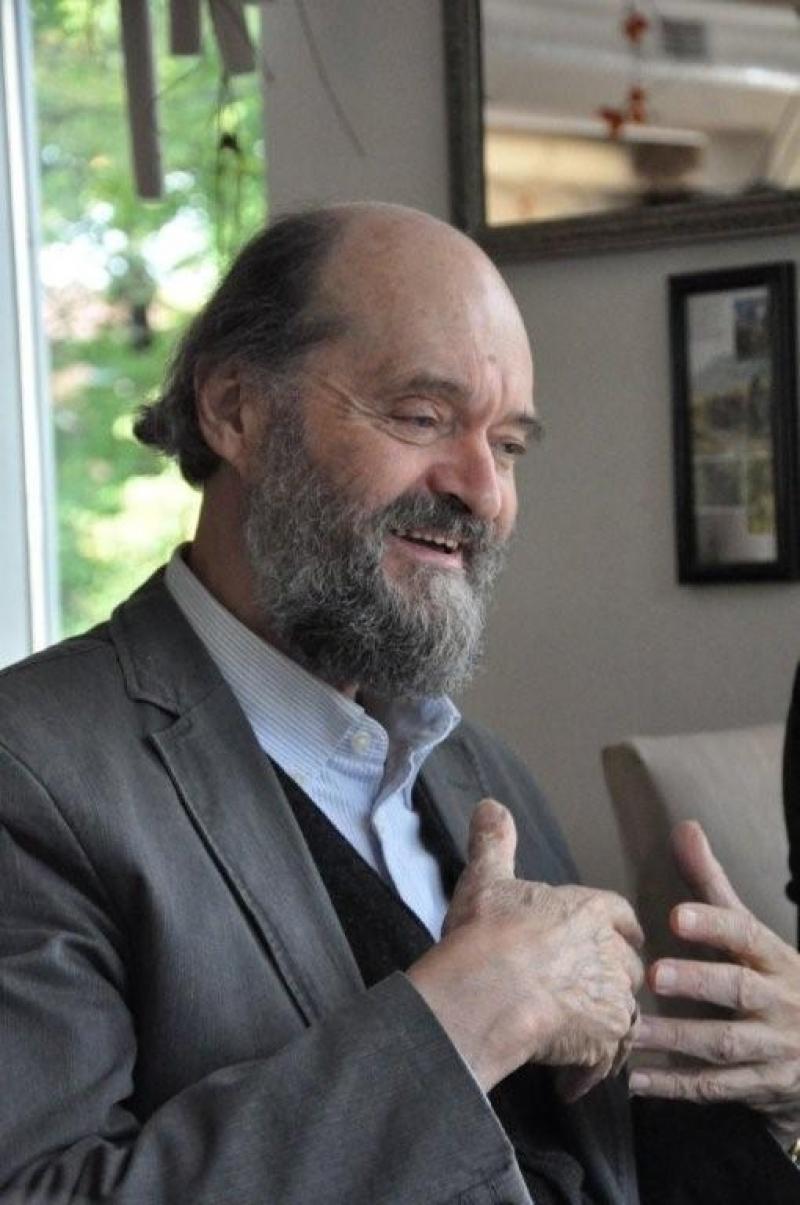

The difficulty that Simon Broughton faced when trying to get Pärt to talk about his music on camera chimes entirely with my own experience when I came to write my PhD on the composer. I had the good fortune of meeting Pärt several times during my research, including the slightly terrifying experience of giving a paper on his Credo in the composer's presence at the Royal Academy of Music. One particularly memorable afternoon was spent with Arvo and his wife, Nora, at the Orthodox Monastery of St John the Baptist in Tolleshunt Knights, Essex (the Pärts owned a property a short drive away). While Pärt was perfectly happy to answer my questions about his work list, which pieces had been withdrawn for revision, and so on, he responded to questions about his music by giving me Archimandrite Sophrony’s weighty hardback tome, Saint Silouan the Athonite. “If you want to understand my music,” he told me, “read this.” The music, you inferred, must speak for itself.

Born on 11 September 1935 in Paide, Estonia, Pärt studied composition at the Tallinn Conservatory under the influential teacher Heino Eller. Although best known for the works he has composed since the unveiling of the “tintinnabuli” style, announced in 1976 by Für Alina, Pärt had already become something of an enfant terrible in Soviet musical circles during the 1960s. The darkly expressive orchestral piece Nekrolog (1960), Pärt's first mature work, caused a scandal by being the first Estonian work to employ serialism, incurring the wrath of no less a person than the all-powerful head of the Soviet Composers’ Union, Tikhon Khrennikov. Not a man to be trifled with.

Using other avant-garde techniques such as pointillism and aleatoricism, Pärt wrote further experimental works including Perpetuum Mobile (1963), Symphony No 1 (1964), Diagrams (1964) and Musica Sillabica (1964) in which extremes of dynamics and texture at times reach cumulative points of such intensity that the music seems to be on the verge of complete collapse.

Becoming dissatisfied with serial technique, Pärt searched for another means of furthering his musical development, resulting in his use of “borrowed” tonal gestures and the adoption of baroque and classical forms, such as the comic finality of the musical catch phrase which brings Quintettino (1964) to an ambivalent conclusion; the grotesque distortion of Bach’s Sarabande from English Suite No 6 in the central movement of Collage on B-A-C-H (1964); and the ironic cadenza and grandiloquent tonal conclusion of the cello concerto Pro et Contra (1966).

The remarkable Credo (1968), which represented both the culmination of his early style and the first work in which he set a religious text, is a pivotal work in Pärt's output. Scored for piano, chorus and orchestra, the two outer sections are based on a pristine C major tonality – specifically the C major Prelude from Book I of Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier – while the central triptych journeys into chaos and a wild, improvised climax. An exhilarating cri de coeur of a piece, the composer's musical affirmation of faith ("Credo in Jesum Christum") ensured that the work was banned in the Soviet Union following its first performance.

Following Credo, Pärt reached a creative impasse and underwent a dramatic reorientation of style. The impulse for this change was twofold, springing on the one hand from an inner musical necessity brought about by his encounter with plainchant and other early music, and on the other by his gradual religious awakening (originally Lutheran, Pärt converted to the Russian Orthodox Church). Rather than appropriate the stylistic conventions of past composers, his compositional concerns now became directed towards a very specific goal: the setting of religious texts. It was no longer enough to simply import tonality by wearing a Bachian stylistic mask as he had done in Credo.

The surprising richness of the work’s closing Gratiarum Actio is one of the most transcendent passages of 20th-century sacred music

While the techniques and processes of early music have proved to be a continuing source of fascination and inspiration for many contemporary composers – Louis Andriessen, Peter Maxwell Davies and Steve Reich all readily spring to mind – no other composer has made such a profound study of this music, and with such fruitful results, as Pärt. Aside from the importance of specific models from early music, Pärt's in-depth exploration compelled him to rebuild his musical language from scratch. Anything that had no properly audible, as opposed to merely textural, purpose no longer had a place in his work.

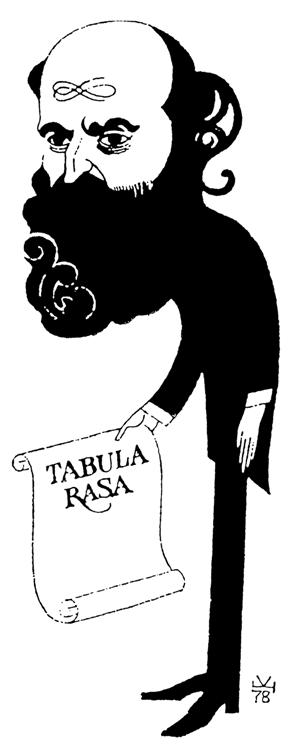

Tabula Rasa. Cartoon portrait by Heinz Valg (1978)  To uncover what he considered to be the startling power of unadorned melody, Pärt wrote reams of technical exercises using just a single line of music. Apart from its innate inner strength, what impressed the composer most about plainchant was its cohesiveness, its clarity and its flexibility. From working with just a single line of music, Pärt then began to investigate the potential of using two voices, before intuitively discovering the simple two-part unit that was to become the basis of the tintinnabuli style: a generally step-wise melodic line accompanied by a triadic or “tintinnabuli” harmony (tintinnabulum literally means “small bell”). Subtly varied from work to work – the composer determining the rules of the game for each piece – the tintinnabuli style has proved extremely flexible.

To uncover what he considered to be the startling power of unadorned melody, Pärt wrote reams of technical exercises using just a single line of music. Apart from its innate inner strength, what impressed the composer most about plainchant was its cohesiveness, its clarity and its flexibility. From working with just a single line of music, Pärt then began to investigate the potential of using two voices, before intuitively discovering the simple two-part unit that was to become the basis of the tintinnabuli style: a generally step-wise melodic line accompanied by a triadic or “tintinnabuli” harmony (tintinnabulum literally means “small bell”). Subtly varied from work to work – the composer determining the rules of the game for each piece – the tintinnabuli style has proved extremely flexible.

An outpouring of works followed in 1977 – something of an annus mirabilis for Pärt - including three of the most enduring works of the new style: the seemingly endless melodic descents of Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten; the punctilious melodic elaborations of the double violin concerto Tabula Rasa; and the startling gesturelessness of Fratres.

The most perfect realisation of the tintinnabuli style came with the St John Passion (1977-82). Wishing to act merely as a vessel for the music, Pärt decided from the very beginning that the Passion text would yield the entire substance of the work. Setting the text syllabically throughout, every single phrase structure, note value and caesura between phrases is governed entirely by the punctuation of the text. The result is a work of profound restraint, at once both detached and deeply affecting. The surprising richness of the work’s closing Gratiarum Actio – a final offering of praise and thanks which is heard in its entirety in the forthcoming episode of Sacred Music – is one of the most transcendent passages of 20th-century sacred music.

From the troubled angst of Credo to the celestial atemporality of the St John Passion, Pärt’s has been one of contemporary music’s most fascinating journeys

Pärt has remarked that it is the nature of the language being set that predetermines to a remarkable degree the specific character of each vocal piece. From working predominantly with Latin texts, his many commissions have seen him setting Italian in Dopo la vittoria (1996), Spanish in the psalm setting Como cierva sedienta (1998), and numerous settings in English. The latter include the stylised invocations and responses of Litany (1994), a return to St John’s Gospel for I Am the True Vine (1996), and The Deer's Cry (2007), a setting in English of St Patrick’s Breastplate (“Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me...”). Of especial significance is Pärt’s setting of Church Slavonic, a language used exclusively in ecclesiastical texts, in the imposing Kanon Pokajanen (1997). As evidenced by the extract of the piece heard in Sacred Music, its sound-world appears to place it within the illustrious tradition of Russian Orthodox Church music. What all of these works vividly illustrate is the way in which the tintinnabuli style can absorb new textural and harmonic approaches.

From the troubled angst of Credo to the celestial atemporality of the St John Passion, Pärt’s has been one of contemporary music’s most fascinating journeys.

Three essential recordings

Pärt’s music has been incredibly well served on disc, notably by ECM New Series, to the extent that his ever-increasing discography has become difficult to keep up with. The following three recordings, however, are essential.

Tabula Rasa (ECM New Series)

Three purely instrumental classics of the tintinnabuli style: Fratres, Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten and Tabula Rasa. Find on Amazon

Passio (ECM New Series)

Pärt’s austere masterpiece, conducted by one of his foremost interpreters, Paul Hillier. Find on Amazon

Kanon Pokajanen (ECM New Series)

A stunning performance of the Canon of Repentance by the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir. Find on Amazon

- Read theartsdesk Q&A with Simon Russell Beale

- The third episode of Sacred Music - "Górecki and Pärt" - is broadcast on Friday 26 March at 7.30pm on BBC Four.

- Watch episodes one and two on BBC iPlayer

- Watch Björk interview Pärt on YouTube

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Leif Ove Andsnes, Wigmore Hall review - colour and courage, from Hardanger to Majorca

Bold and bracing pianism in favourite Chopin and a buried Norwegian treasure

Leif Ove Andsnes, Wigmore Hall review - colour and courage, from Hardanger to Majorca

Bold and bracing pianism in favourite Chopin and a buried Norwegian treasure

Chamayou, BBC Philharmonic, Wigglesworth, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - Boulez with bonbons

Assurance and sympathy from Mark Wigglesworth for differing French idioms

Chamayou, BBC Philharmonic, Wigglesworth, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - Boulez with bonbons

Assurance and sympathy from Mark Wigglesworth for differing French idioms

Classical CDs: Antiphons, ale dances and elves

Big box sets, neglected symphonies and Norwegian songs

Classical CDs: Antiphons, ale dances and elves

Big box sets, neglected symphonies and Norwegian songs

Davis, National Symphony Orchestra, Maloney, National Concert Hall, Dublin review - operetta in excelsis

World-class soprano provides the wow factor in fascinating mostly-Viennese programme

Davis, National Symphony Orchestra, Maloney, National Concert Hall, Dublin review - operetta in excelsis

World-class soprano provides the wow factor in fascinating mostly-Viennese programme

Best of 2024: Classical music concerts

Young and old in excelsis, and competition finales turned into winning programmes

Best of 2024: Classical music concerts

Young and old in excelsis, and competition finales turned into winning programmes

Spence, Perez, Richardson, Wigmore Hall review - a Shakespearean journey in song

A festive cabaret - and a tenor masterclass

Spence, Perez, Richardson, Wigmore Hall review - a Shakespearean journey in song

A festive cabaret - and a tenor masterclass

Best of 2024: Classical CDs

Our pick of the year's best classical releases

Best of 2024: Classical CDs

Our pick of the year's best classical releases

First Person: cellist Matthew Barley on composing and recording his 'Light Stories'

Conceived a year ago, a short but intense musical journey

First Person: cellist Matthew Barley on composing and recording his 'Light Stories'

Conceived a year ago, a short but intense musical journey

The English Concert, Bicket, Wigmore Hall review - a Baroque banquet for Christmas

Charpentier's charm, as well as Bach's bounty, adorn the festive table

The English Concert, Bicket, Wigmore Hall review - a Baroque banquet for Christmas

Charpentier's charm, as well as Bach's bounty, adorn the festive table

Classical CDs: Woden, waltzes and watchmaking

Big box sets, a great British symphony and a pair of solo cello discs

Classical CDs: Woden, waltzes and watchmaking

Big box sets, a great British symphony and a pair of solo cello discs

Messiah, Wild Arts, Chichester Cathedral review - a dynamic battle between revelatory light and Stygian gloom

This supple inventive interpretation of the 'Messiah' thrillingly delivers the story

Messiah, Wild Arts, Chichester Cathedral review - a dynamic battle between revelatory light and Stygian gloom

This supple inventive interpretation of the 'Messiah' thrillingly delivers the story

Add comment