Britten: The Canticles, Linbury Studio Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Britten: The Canticles, Linbury Studio Theatre

Britten: The Canticles, Linbury Studio Theatre

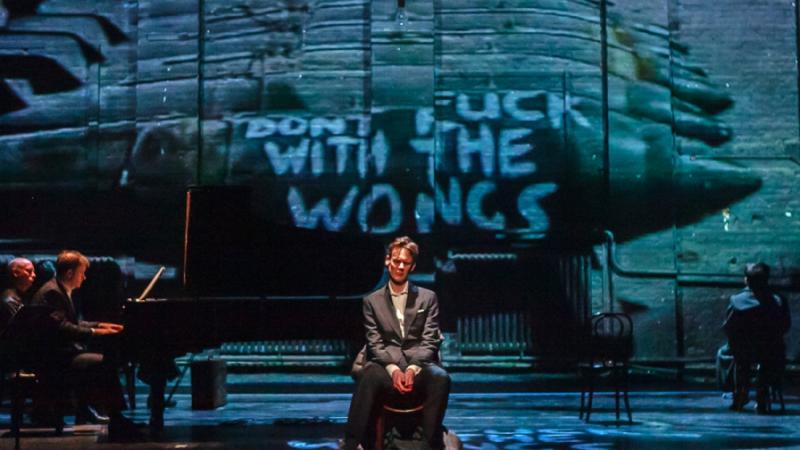

Attraction and repulsion in Britten's baffling Canticles, equally bafflingly staged

As good old Catullus put it, I hate and love, you may ask why. No doubt it's my job as a critic to probe such difficult responses to Britten's Canticles. Why am I so repelled by the sickly-sweet lullaby Isaac sings just before daddy's about to put him to the sword in Canticle II, then so haunted by the sombre war requiem of Britten's Edith Sitwell setting, Canticle III?

The only consistency about this odd hour's internment, reaching London from Brighton and Snape, is Paule Constable's hauntingly lit arena, and perhaps her staging of the least approachable canticle of all, setting Eliot's "The Journey of the Magi" as a creepy three-part narrative for countertenor, tenor and baritone (more much-needed anchoring from Benedict Nelson). The reason it works is because Constable trusts the singers, wearing coats and carrying suitcases, to paint the story, with a little help from the shifting light around them.

Bartlett's dumbshow breakfast scene between two 1930s lovers (Edward Evans and Peter Bray) for Canticle I, "My beloved is mine", is a poignant enough response to one of Britten's many lovesongs to his life-partner Peter Pears. But it interferes with the rather placid voice-and-piano narrative rather than complementing it. And Bostridge's body language is the thing the director really needs to work on, to stop the bending and paradoxically at the same time to unbend our tortuous tenor.

Puzzling, too, is Scott Graham's choreography to "Abraham and Isaac" (dancers Chris Akrill and Gavin Persand pictured right). Is it trying to underline what I feel about the setting, that here is another of Britten's queasy innocence-and-experience works stemming from his extraordinary revelation to trusted sources that he was raped by a schoolmaster, possibly even abused by his father? Might the lingering-on of malign consequences into adulthood be a justification for using the most liquid-voiced of all countertenors, Iestyn Davies, as the son rather than any of the trebles or boy altos around today who might do the part a more appropriate justice?

Puzzling, too, is Scott Graham's choreography to "Abraham and Isaac" (dancers Chris Akrill and Gavin Persand pictured right). Is it trying to underline what I feel about the setting, that here is another of Britten's queasy innocence-and-experience works stemming from his extraordinary revelation to trusted sources that he was raped by a schoolmaster, possibly even abused by his father? Might the lingering-on of malign consequences into adulthood be a justification for using the most liquid-voiced of all countertenors, Iestyn Davies, as the son rather than any of the trebles or boy altos around today who might do the part a more appropriate justice?

Certainly the grim undertow of the Sitwell setting, "Still Falls the Rain", came as something of a relief, though you feel this is the toughness that should have been applied to the horrid Old Testament tale. Bostridge, a haunting tenor who still disarms with the lack of a vocal core to his superb artistry, came into his own here as a ghost-voice, unforgettable in the refrains and spookily intertwined at times with Richard Watkins's peerless horn playing. Artist John Keane's film was as apt as Derek Jarman's montage of war footage for the Libera me in his film of War Requiem; yet still, in both cases, one has to ask if image can add any more to the austere powere of the music. Imagery was rigorously focused, too, in Julius Drake's superlatively clear interpretations of four very different piano parts.

A dancing Narcissus (Dan Watson) as choroeographed by Wendy Houston played off rather better against the late distillation of Canticle V, which Britten wrote shortly before his death, providing a role for harpist Osian Ellis - again, flawlessly taken here by Sally Pryce - when he could no longer partner Pears at the piano. It was, no question, a fine and testing tribute of an evening to the shifting styles of nearly three decades' compositional mastery. That it left a nasty taste, in my mouth at any rate, had to do with both the works and the productions. Good or bad, again, you may ask which, and again I still can't tell you.

- Two more performances at the Linbury tonight and tomorrow, sold out: try for returns

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment