Classical CDs Weekly: Brahms, Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs Weekly: Brahms, Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky

Classical CDs Weekly: Brahms, Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky

Romantic orchestral music, a bleak Soviet symphony and a jazzy ballet reinvention

There’s a glut of Brahms symphonies on disc this autumn, with live recordings from Valery Gergiev and a new Leipzig cycle on Decca from Riccardo Chailly. As an appetizer, you could do far worse than to investigate this handsomely recorded, well performed Telarc set. Conductor John Axelrod believes that each of Brahms’s four symphonies has a distinct character, all directly inspired by his unrequited love for Clara Schumann. Arguing that each work reflects a different aspect of Clara’s personality seems a step too far – Brahms 2 is much more than a bucolic, pastoral idyll, and no 4 is not just a gruff E minor rant. Axelrod has accompanied each symphony with a set of Clara Schumann lieder, chosen to match what he feels is the prevailing mood. Having different voices to sing each set is an inspired touch – Indra Thomas is superb in the set accompanying Symphony no 4, and Nicole Cabell’s lighter tone suits the warmer cast of the songs following no 2. But how frustrating not to have the texts handy - they can be downloaded, but who wants to listen to a CD while staring at a computer screen?

But don’t be put off – the two symphonies are beautifully done. The Fourth is shrewdly paced and beautifully coloured, the Milan orchestra never sounding too dark and murky. It’s easy to underestimate the modernity of this work, its textures veering from fruity richness to parched austerity. Axelrod nails the passage leading to the first movement recapitulation, the material thinning out before the main theme’s spectral reprise. Rarely has the last movement’s opening chorale sounded so organ-like, and the glowering final pages have plenty of energy. It’s a weighty work, but it shouldn’t be a depressing one. No 2’s grave slow movement is sublime, and the subsequent lightening of mood skillfully judged. Well worth investigating.

The opening tempo marking, Allegretto poco moderato, suggests that we’re about to hear something light, witty, elegant. No chance – this pulverizing performance of Shostakovich’s ill-starred Symphony no 4 is like being kicked in the face. In a good way. Famously, its composer withdrew the work shortly after rehearsals began in 1936, and it wasn’t performed until 1961. There’s a good quote in Richard Whitehouse’s sleeve note; Shostakovich, talking after an early performance of his acclaimed th Symphony, remarked that “I finished the symphony fortissimo and in the major… I wonder what everyone would be saying if I had finished it pianissimo and in the minor?” The Fourth’s unsettling whisper of a close can pack a devastating punch, and Vasily Petrenko’s new version is as good as any around. The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic play out of their skins – everything’s secure, but nothing sounds glib or slick. I’m thinking of the first movement’s roaring lower brass, or the extraordinary, breathless string fugato. The lengthy cor anglais solo near the movement’s coda is stark and lonely, and the sudden orchestral flareup seconds before the close is wonderfully sardonic.

Petrenko’s percussionists make the Scherzo’s eerie fade sound effortless, but it’s Petrenko’s Finale which really stuns. Shostakovich’s nods to Mahler are everywhere – the introductory funeral march is terrific, as is the raucous, unsettling circus music which follows. It’s funny, but leaves a bitter taste. All culminates in one of the loudest perorations imaginable and the most emotionally devastating of symphonic fadeouts, replete with a twisted reference to the major-minor triad motif heard in Mahler 6. Petrenko brings unusual coherence to the movement; it sounds like a long, single take. Unmissable.

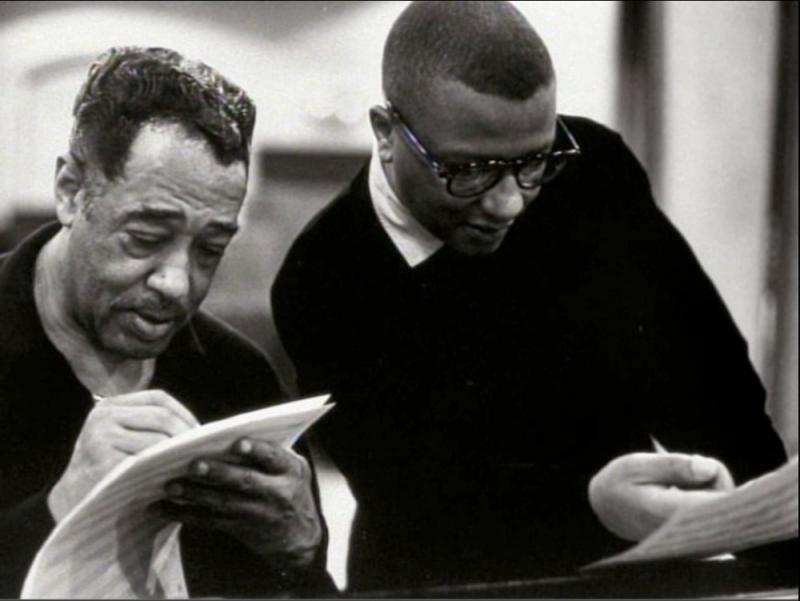

Steven Richman’s Harmonie Ensemble recorded one of the greatest ever Gershwin discs a few years ago. This brilliant follow-up combines Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite with a neglected revamp concocted in 1960 by Duke Ellington and his long-time collaborator and arranger Billy Strayhorn. Strayhorn became a member of Ellington’s band after meeting the great man in the late 1930s, the Duke later admitting that "Billy Strayhorn was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brain waves in his head, and his in mine." The Ellington/Strayhorn Nutcracker is sublime, and this recreation is a thing of wonder, sounding as if it could have been recorded in, er, 1960, but with better sonics. Tchaikovsky’s original is reinvented with staggering cheek and flair. Tempi are stretched. Waltzes become foxtrots. Reedy wind sonorities emphasise the original suite’s harmonic boldness, and everything is underpinned by Hassan Shakur’s emphatic bass playing.

Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy becomes Sugar Rum Cherry, celeste replaced by a pair of saxophones. The suite closes with the Arabian Dance revamped as the Arabesque Cookie, bouncing along under an insistent percussion riff and with some classy muted brass. All fantastic, and the results never detract from the magnificence of Tchaikovsky’s original. Which occupies the first half of this disc. It’s played here by a more conventional orchestral incarnation of the Harmonie Ensemble, here sounding like the best pit orchestra you’ve ever heard. Listen to that bassoon line chugging away underneath the Chinese Dance, or the tight brass in the March. Fantastic fun, and nice sleeve art too.

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Donohoe, RPO, Brabbins, Cadogan Hall review - rarely heard British piano concerto

Welcome chance to hear a Bliss rarity alongside better-known British classics

Donohoe, RPO, Brabbins, Cadogan Hall review - rarely heard British piano concerto

Welcome chance to hear a Bliss rarity alongside better-known British classics

London Choral Sinfonia, Waldron, Smith Square Hall review - contemporary choral classics alongside an ambitious premiere

An impassioned response to the climate crisis was slightly hamstrung by its text

London Choral Sinfonia, Waldron, Smith Square Hall review - contemporary choral classics alongside an ambitious premiere

An impassioned response to the climate crisis was slightly hamstrung by its text

Goldberg Variations, Ólafsson, Wigmore Hall review - Bach in the shadow of Beethoven

Late changes, and new dramas, from the Icelandic superstar

Goldberg Variations, Ólafsson, Wigmore Hall review - Bach in the shadow of Beethoven

Late changes, and new dramas, from the Icelandic superstar

Mahler's Ninth, BBC Philharmonic, Gamzou, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - vision and intensity

A composer-conductor interprets the last completed symphony in breathtaking style

Mahler's Ninth, BBC Philharmonic, Gamzou, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - vision and intensity

A composer-conductor interprets the last completed symphony in breathtaking style

St Matthew Passion, Dunedin Consort, Butt, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - life, meaning and depth

Annual Scottish airing is crowned by grounded conducting and Ashley Riches’ Christ

St Matthew Passion, Dunedin Consort, Butt, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - life, meaning and depth

Annual Scottish airing is crowned by grounded conducting and Ashley Riches’ Christ

St Matthew Passion, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin review - the heights rescaled

Helen Charlston and Nicholas Mulroy join the lineup in the best Bach anywhere

St Matthew Passion, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin review - the heights rescaled

Helen Charlston and Nicholas Mulroy join the lineup in the best Bach anywhere

Kraggerud, Irish Chamber Orchestra, RIAM Dublin review - stomping, dancing, magical Vivaldi plus

Norwegian violinist and composer gives a perfect programme with vivacious accomplices

Kraggerud, Irish Chamber Orchestra, RIAM Dublin review - stomping, dancing, magical Vivaldi plus

Norwegian violinist and composer gives a perfect programme with vivacious accomplices

Small, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - return to Shostakovich’s ambiguous triumphalism

Illumination from a conductor with his own signature

Small, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - return to Shostakovich’s ambiguous triumphalism

Illumination from a conductor with his own signature

LSO, Noseda, Barbican review - Half Six shake-up

Principal guest conductor is adrenalin-charged in presentation of a Prokofiev monster

LSO, Noseda, Barbican review - Half Six shake-up

Principal guest conductor is adrenalin-charged in presentation of a Prokofiev monster

Frang, LPO, Jurowski, RFH review - every beauty revealed

Schumann rarity equals Beethoven and Schubert in perfectly executed programme

Frang, LPO, Jurowski, RFH review - every beauty revealed

Schumann rarity equals Beethoven and Schubert in perfectly executed programme

Levit, Sternath, Wigmore Hall review - pushing the boundaries in Prokofiev and Shostakovich

Master pianist shines the spotlight on star protégé in another unique programme

Levit, Sternath, Wigmore Hall review - pushing the boundaries in Prokofiev and Shostakovich

Master pianist shines the spotlight on star protégé in another unique programme

Classical CDs: Big bands, beasts and birdcalls

Italian songs, Viennese chamber music and an enterprising guitar quartet

Classical CDs: Big bands, beasts and birdcalls

Italian songs, Viennese chamber music and an enterprising guitar quartet

Add comment