Classical CDs Weekly: Ruperto Chapí, Rossini, Walton | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs Weekly: Ruperto Chapí, Rossini, Walton

Classical CDs Weekly: Ruperto Chapí, Rossini, Walton

Vibrant string quartets, an upbeat Mass setting and late music from a 20th-century British composer

Think string quartet and you tend to think Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart. Maybe Bartók and Shostakovich. But generally something respectable, well-behaved and Northern European. Not Spanish, unless it's the one by Ravel. So you need to make the acquaintance of Ruperto Chapí. He came to prominence in the late 19th century as a zarzuela composer. Born near Alicante in 1851, he trained in Rome and Paris, returning to Spain in 1880. In the years immediately before his death in 1909 he composed four string quartets, a genre which had hitherto been absent from Spanish musical culture. Chapí's first two quartets are paired on this disc, and they're unassumingly wonderful – both large-scale works, bubbling with energy, colour and a refreshingly unsentimental cheeriness. Chapí's compositional craft never lets him down, and it's obvious that he knew and understood the quartets of Mozart and Beethoven. What gives them a unique flavour is their harmonic zest, coupled with a reliance on ostinati that never becomes wearing. There's a lot of repetition, but it's never dull – violinist Saúl Bitrán writes in his sleeve note that the music reminds him of “those languid summer afternoons in small Spanish villages, where time appears to stand still”.

The rate of harmonic and motivic change is often uneventful, but the metric pace rarely lets up. These quartets don't stand still. There's a moment at the start of the 1st Quartet's last movement when you think things have at last, if fleetingly, slowed down. But no – after a gorgeous, recitative-like intro, the music bounds forward, accompanied by the catchiest of rhythms. The 2nd Quartet's melodies are more obviously Spanish in inflection – Google Phrygian mode if you're curious to understand why. The Quasi presto last movement's minor-key dramatics are thrilling, as is the full-blooded, optimistic resolution. Mexico's Cuarteto Latinoamericano give us idiomatic, assured performances. You'd expect nothing less from a group containing three brothers. Joyous stuff, and very decently recorded. Can we have a second volume please?

If you're searching for an upbeat sacred choral work, Rossini's Petite Messe solennelle is up there alongside Poulenc's Gloria. Rossini's mass doesn't quite match its title – it lasts over an hour, and it's not especially solemn. One of the composer's "sins of old age", a work originally intended to be a "short secular requiem", quickly grew into something more substantial. Rossini's quirkier first version, first performed in 1864, has the vocal forces accompanied by two pianos and harmonium, but this new recording gives us Davide Daolmi's critical edition of Rossini's unfussy orchestration. It's a piece to fall in love with, irresistibly fusing spirituality with jauntiness.

Conductor Ottavio Dantone leads his Parisian forces in a flowing, incisive performance. I defy anyone not to smile at tenor Michael Spyres' effortless "Domine Deus" in the Gloria, or at the brief choral flourish near the start of "Cum sancto spiritu". And has there ever been a more deliciously incongruous blend of music and lyrics than that which we get in Rossini's tiny "Crucifixus"? Sonorous low brass restore a touch of gravitas in the "Et resurrexit", and there's an unexpectedly assertive close to the Agnus dei. Immaculate choral singing from accentus and nimble orchestral playing from the Orchestre de Chambre de Paris. Dantone's soloists don't disappoint, notably soprano Julia Lezhneva.

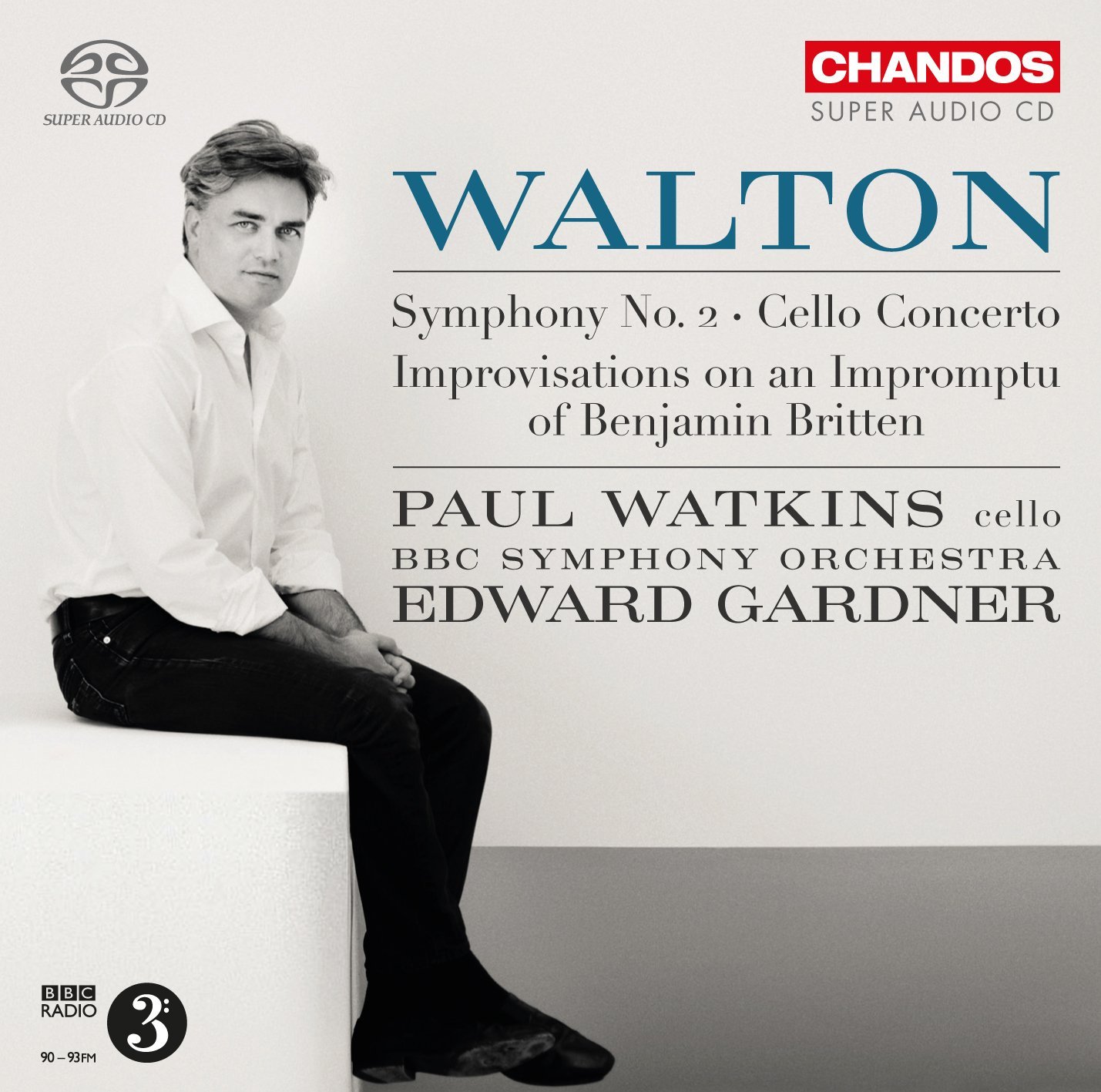

Walton and Britten weren't close friends. The older composer resented the younger upstart's rapid rise, but the pair maintained a courteous professional relationship. Britten commissioned Walton's opera The Bear for Aldeburgh, and Walton asked Britten for permission to use the third movement of his Piano Concerto as the basis of his Improvisations, written for the San Francisco Symphony in the late 1960s. Edward Gardner's new recording of this attractive, clever work is a corker. The brief Moderato third section is so exquisite that it's worth the cost of the whole CD; Walton's ticking woodwinds accompanying a splintered, slinky version of Britten's theme. There's a brief, passionate eruption which Gardner wisely milks to the hilt. The work's close is in Walton's brittle late style, the stabs of brass underlined with bright percussion. It's a bracing amuse-bouche for Walton's rather lovely Cello Concerto, which I'm convinced is the best of his three string concertos. Soloist Paul Watkins impresses in the quicksilver scherzo, and compels in the last movement's ruminative cadenzas. And how good to hear the BBC Symphony Orchestra on such outstanding form; the concerto's slow, contemplative fade is delicious.

Gardner achieves similar miracles with Walton's still undervalued Symphony no 2. The BBC brass excel; muted trombones near the end of the first movement really snarl, and a terrifying horn solo in the Finale is flawless. This is such an entertaining work – the tunes are good, the orchestration is dazzling and it says all it has to say in less than 30 minutes. Gardner's deft, spiky reading is a winner, from the Stravinskian opening flourish to a last movement which never sprawls. The coda's fireworks are magnificent, and you can actually hear the single tubular bell note. Chandos's widescreen sound is what the piece deserves – you'll hear things in this recording that you've never heard before. Listen to it at high volume when everyone's gone out.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Add comment