Electronica: BBC Concert Orchestra, Will Gregory Moog Ensemble, Hazlewood, QEH | reviews, news & interviews

Electronica: BBC Concert Orchestra, Will Gregory Moog Ensemble, Hazlewood, QEH

Electronica: BBC Concert Orchestra, Will Gregory Moog Ensemble, Hazlewood, QEH

Jonny Greenwood overreaches while Will Gregory strikes Moog-driven gold

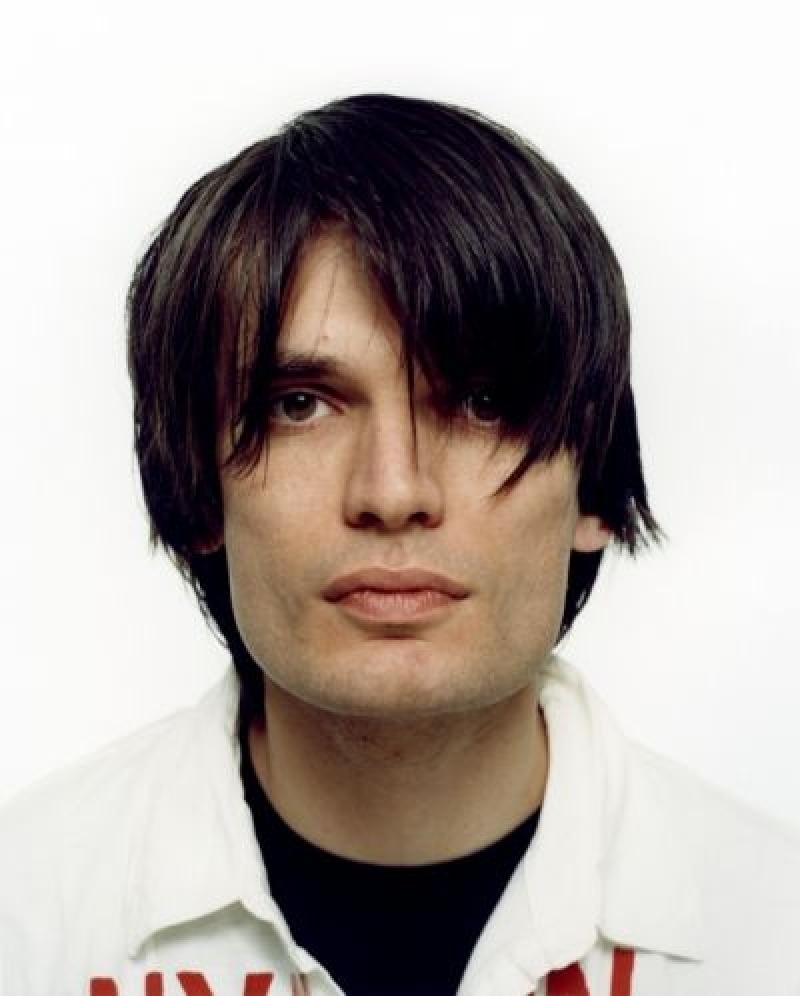

I would call them burglars: musicians from the experimental rock, electronica and sound-art traditions who cross the genre divide, sneak into the world of classical music, pillage its more easily pillaged valuables, thieve its respectability, filch its original ideas, and sprint back breathlessly to their wide-eyed fans to show off this brilliantly clever "new" classical music (much of which is made up of techniques that George Benjamin would have grown out of by the age of six) in double qui

Greenwood's anaemic attempt at composition, smear, from 2004, a work that seems so damningly terrified of harmonising itself or evolving itself or colouring itself in any way at all that it barely qualifies as more than a cowering shadow of a work, was in good, or rather bad, company. Both the first half's other works by Bernard Herrmann and André Jolivet were nearly as useless. Both, however, had the excuse, unlike the Greenwood, of being incidental music. Herrmann's suite was from the 1950s sci-fi movie The Day the Earth Stood Still and Jolivet's Suite delphique from a 1943 performance of Iphigenia in Aulis. Therefore both had been deliberately written to be insufficient.

Still, Jolivet is a second-rater at the best of times. Why he and this rather dull Herrmann suite were chosen to open a showcase of these beguiling electronic instruments - the theremin and ondes Martenot - beats me. I realise that the BBC Concert Orchestra were trying to ease a new crowd into this unfamiliar sound-world but could they not have performed a chunk of Turangalîla instead?

And just as my mood couldn't get any worse came three works that were as exquisite and varied as the first three were thin and insipid. Will Gregory's Journeys into the Sky was extraordinary. It took the form of a five-movement concerto for six synthesisers and two mini-Moogs. The movements each deal with a different aspect of man's various attempts through history to conquer flight.

The first is about the Flying Dream. Musically one could see it as a short but bold reworking of facets of The Rite of Spring, woodwind exploding uncontrollably from staccatoed and intermittently syncopated string and Moog ostinati, capped with a Beethovenian climactic flash or two. The second, Too Far North, is a chilly but no less atmospheric slow movement. The third, Mercury Balls, has an infectiously slippery walking bass. The fourth, Light-Headed, is made up of a lush string bed that irregularly loops itself in Reichian and Ligeti-like ways to create a kaleidoscope of accents. The finale, If Man Had Wings, offers a much appreciated mooged boogie-woogie that transcends itself and then returns and escapes.

Gregory's ability to juggle colour, structure and styles is second to none. The work is the basis for an opera commission to be premiered at the Queen Elizabeth Hall by the BBC Concert Orchestra next year and frankly I can't wait. Next came a rarity from two names who always appear as footnotes in the development of 20th-century music: Otto Luening and Vladimir Ussachevsky. Good on Charles Hazlewood - who conducted with real commitment throughout the evening - for dragging A Poem in Cycles and Bells - for tape recorder and orchestra from the depths of obscurity. It is a beautiful little work and deserves a thorough exposition of its delights.

After a rich, resplendent start, the string body begins evaporate, leaving a sultry moment for woodwind. Gerald Finzi rears his head in a passage of pure English pastoralism (God knows why or how). The entry of the tape, which contains music of a freer pastoral nature, includes a beautifully over-vibbed 1950s flute solo and then a piano, both of which are stretched and echoed and left to float and burble like a spirit summoned at a séance. Orchestra and tape court, then come together slowly, a dance emerging through a melting of the echoed beat. There is the arrival of a ricochet, then a waltzing bounce that chivvies the action along. We climax on a sound that is trilled and percussed into refulgent sunlight. What remarkable sweet glory there is in this work.

Miklós Rózsa's Spellbound Concerto for Orchestra displays a love of a more sweeping, eyes-closed, lips-clasped sort. There's some tough but brilliantly delivered theremin playing from Celia Sheen, which seemed to be a psychedelic summoning up of Dalí's contribution to the Hitchcock film on which this work is based. The orchestra sounded especially handsome in full Hollywood flow.

Though we ended with an orchestral arrangement of Kraftwerk's The Model that didn't really work, the evening came good. Jarvis Cocker presided over events nice and drily. Thoughts of the rubbishiness of the first half were quickly banished from our minds. I left almost a happy customer. Like Cocker, I would have liked to have seen the great trautonium being given a hearing; an outing of Hindemith's marvellous Concertpiece for Trautonium and Strings should have been accommodated in this electronic celebration. As too should at least one of the early works of Varèse, the greatest electronic composer who never was.

- Check out the rest of the BBC Concert Orchestra season

- Check out the rest of the season at the Southbank Centre

- Find Jonny Greenwood on Amazon

- Find Will Gregory on Amazon

- Find Ussachevsky and Luening on Amazon

- Find Miklós Rózsa on Amazon

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

...

...

...

...