What's not to like, or love, would have to be the sensible response to both the opening programme of Kings Place's year-long Cello Unwrapped festival at Kings Place and its life-enhancing execution. Symmetries abounded – between Alban Gerhardt's double-stopping summons with the "Canto Primo" of Britten's First Cello Suite at the start and his late-night farewell symphony, Kodály's towering Sonata for solo cello; also between two glistening suites for which the label "neo-Baroque" is too narrow, Ravel's Le Tombeau de Couperin and Stravinsky's Pulcinella.

Gerhardt's charismatic style was very much at the heart of the evening. "He's a beast," wrote a young cellist to me on hearing of the event. In a good way? Absolutely, came the reply. A genial and engaging beast, to be sure, who broke the G string in the cadenza of the Tchaikovsky, with its massive demands towards superficially modest ends, and gladly took over principal Aurora cellist Sébastien van Kuijk's instrument with less than a minute's pause (the very moment pictured below by Aurora's in-house photographer Nick Rutter).

Hard to say whether or not the adrenalin flowed any faster after this, it was already at such a level, but of course the "show must go on" attitude thrilled the audience and one of many children present – this was a perfect, if long, programme for them – was the first to his feet at the end. The encore, making no demands on the broken G string and consequently allowing Gerhardt to bring back his own more sonorous cello, was typically thoughtful: Resignation, a little miniature for soloist, lower strings and woodwind, by the cellist and composer Wilhelm Fitzenhagen whose concertos Gerhardt has recorded and whose fiddling around with Tchaikovsky's original Rococo order seems to have stuck (and I'm not as convinced as Gerhardt that it's a good thing).

Never let it be said that the excitement eclipsed any subtleties. Quite apart from the very Auroraesque idea, echoing another early January opening three years ago, of a clever segue, in this case from the Britten movement to Vivaldi's B minor Concerto – an unusual key, incidentally, shared with the Kodály – there were so many deft chamber-musical pauses for air and wry little kicks. And all this only enriched what is already a highly individual work (so much more original, I reckon, than the oft-played Haydn concertos, but that may be a matter of taste).

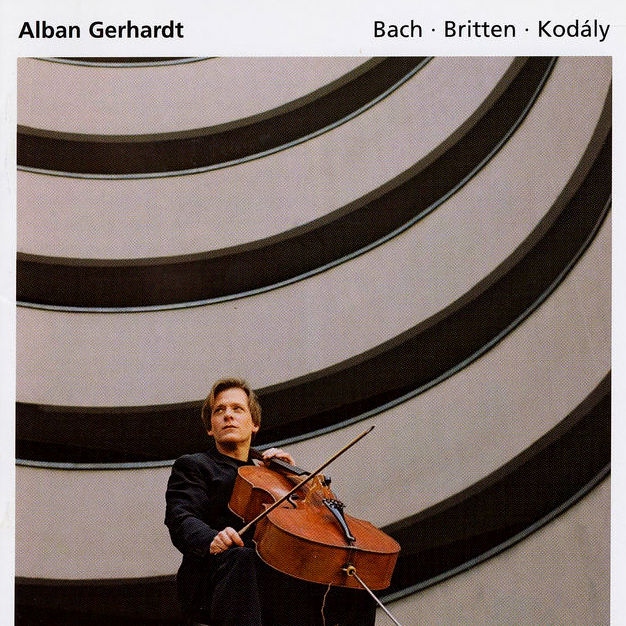

Though Gerhardt's Tchaikovsky was closer to pitch-perfect than most performances I've heard, the high-register playing both here and in the Vivaldi beautifully centred, flawless intonation can't be the name of the game when the musical intensity is so fierce (again, always in a good way). The essence of this Kodály Sonata was its insistence on the listener's total concentration. This has been a powerful testament to Gerhardt's singular creativity since his 2004 recording (pictured right), which turned me on to the piece in a big way. Live, he made a spellbound audience value the silences in between the notes that made their own unheard music, and he was able in the dance-strands which eventually emerge from the severity to conjure a full orchestral thrumming and buzzing. This colossal work is as much an embodiment of Hungarian soul as any of Bartók's masterpieces, and I don't use the word "thrilling" lightly of its cumulative impact at the end of an amazing evening.

Though Gerhardt's Tchaikovsky was closer to pitch-perfect than most performances I've heard, the high-register playing both here and in the Vivaldi beautifully centred, flawless intonation can't be the name of the game when the musical intensity is so fierce (again, always in a good way). The essence of this Kodály Sonata was its insistence on the listener's total concentration. This has been a powerful testament to Gerhardt's singular creativity since his 2004 recording (pictured right), which turned me on to the piece in a big way. Live, he made a spellbound audience value the silences in between the notes that made their own unheard music, and he was able in the dance-strands which eventually emerge from the severity to conjure a full orchestral thrumming and buzzing. This colossal work is as much an embodiment of Hungarian soul as any of Bartók's masterpieces, and I don't use the word "thrilling" lightly of its cumulative impact at the end of an amazing evening.

The orchestra's Ravel and Stravinsky performances were no less remarkable in the way they shone fresh lights on each composer's individuality. It was moving to have the Auroras underline how Ravel, surely the greatest orchestrator of all time, puts so much colour into a single, unorthodox chord; the one which lays the Menuet to rest is pure heaven, and the melancholy inflection beneath a light flute line in the final Rigaudon is another reminder that despite the brio of one great composer's response to another, these miniatures are also memorials to friends lost in the First World War (pictured below: Gerhardt and Collon take a bow).

Aurora principal oboist Thomas Barber had his work cut out in the kaleidoscope of tones demanded both here and in the Pulcinella Suite, which also enriched us as a concerto for orchestra, players so often in dancing pairs with elegant leader Max Baillie and second violinist Eva Thoransdottir lighting the way. Collon's deftness was mostly understated in a positive sense, though he asked for a hair-raising velocity in the Tarantella which these players had no difficulty articulating. Youth and good looks are always a bonus with this band. And from three rows back in the stalls, the sound for one of the largest ensembles to have appeared on the stage of Kings Place's splendid Hall One never overwhelmed. The more I hear in its adaptable surroundings, the more I'm inclined to think it may be London's best classical venue. Which is good, given how many delectable programmes lie ahead in Cello Unwrapped's year-long box of unearthly delights.

Add comment