I Found My Horn special: The Art of Dennis Brain | reviews, news & interviews

I Found My Horn special: The Art of Dennis Brain

I Found My Horn special: The Art of Dennis Brain

The greatest horn player in history? The author of a book in praise of the instrument assesses his legacy

I Found My Horn is both an autobiography of sorts and a biography of sorts. It tells the story of those phases of my life, as a schoolboy and then again aged 40, when I happened to have a French horn in my hands. But it is also an account of the instrument's long and extremely colourful history. In the 20th century that history is inextricably connected to the name of Dennis Brain, probably the greatest soloist the instrument has ever known.

Although he died in a car crash more than 50 years ago, since publication many people have written to me to say that they met him, were taught by him, saw him perform or give a school recital. One man reported that as a schoolboy he'd carried Brain's horn. I went one better than that in the course of my researches: I played Brain's horn. That inglorious moment is described in this extract, from a chapter entitled "Without Fear of Death", alongside a consideration of Brain's impact on the musical world.

I have in my hands the horn of Dennis Brain. His single B flat Alexander. The horn mangled in the car crash

DENNIS BRAIN died in the early hours of Sunday morning, 1 September, 1957. His TR2 slid off the road in heavy rain and hit an oak. An inquest was unable to establish the cause of the accident. No doubt poor weather, lack of sleep and his addiction to speed proved a lethal combination. His death was mourned by a wife, two children and a world of admirers.

His single B flat Alexander 103 was severely damaged. It was retrieved from the wreckage and restored by Paxmans. For many years it stood in the window of the Paxmans shop in Covent Garden. I meet one American horn player, now retired, who remembers going in there as a young man and being asked if he’d like to “have a blow on Dennis’s horn”. He turned down the offer. It seemed to him to be sacrilege.

Since 2002 the instrument has been behind glass at the Royal Academy of Music. Brain’s genealogy is laid out right there in the cabinet. Next to his Alexander is the Alexander “with adaptations by Sansone” played by his uncle Alfred, and the horn made “by Labbaye with Périnet valves by Brown” played by his father, Aubrey. Alfred and Aubrey were the sons of A E Brain, who played fourth horn in the first ever Prom in 1895. Alf spent much of his professional life in Los Angeles. Aubrey, eight years his junior, was principal horn of the inaugural BBC Symphony Orchestra and in 1927 became the first person to record a Mozart horn concerto.

Dennis was taught by his father at the Academy, and made his professional debut alongside him at 17. They played the first Brandenburg concerto. “The famous family keeps up its traditions in the representative of the new generation,” wrote the Daily Telegraph. “Son seconded father with a smoothness and certainty worthy of his name.” But Dennis was to be spared an oedipal confrontation of his own. On Christmas Day of 1940, during a blackout in Bristol where the BBC Symphony Orchestra was based during the war, Aubrey had a bad fall slipping on ice. He was never the same player again. By the end of the war he had retired as a soloist.

Britain went to war soon after Dennis’s 18th birthday. He joined the Royal Air Force and wore military uniform but, as principal horn of the RAF Central Band, and then the RAF Symphony Orchestra, his contribution to the war effort was largely musical, give or take the odd spell on guard duty. A fixture at the National Gallery’s morale-boosting lunchtime concerts, he performed Brahms’s horn trio there no fewer than six times. In the 18 years of his professional life, he managed almost single-handedly to put the solo instrument back on the map for the first time since the death of Mozart, spurring a succession of composers to respond to his virtuosity, and the purity of his sound. Benjamin Britten, returning as a conscientious objector from American exile in 1942 with his companion Peter Pears, was the first major composer provoked into enlarging the literature for Brain.

Britain went to war soon after Dennis’s 18th birthday. He joined the Royal Air Force and wore military uniform but, as principal horn of the RAF Central Band, and then the RAF Symphony Orchestra, his contribution to the war effort was largely musical, give or take the odd spell on guard duty. A fixture at the National Gallery’s morale-boosting lunchtime concerts, he performed Brahms’s horn trio there no fewer than six times. In the 18 years of his professional life, he managed almost single-handedly to put the solo instrument back on the map for the first time since the death of Mozart, spurring a succession of composers to respond to his virtuosity, and the purity of his sound. Benjamin Britten, returning as a conscientious objector from American exile in 1942 with his companion Peter Pears, was the first major composer provoked into enlarging the literature for Brain.

The reviews offered never-ending praise. In 1946: “Was anything like such horn-playing known a generation ago?” In 1948: “Dennis Brain’s horn playing – so expressive, so finely shaded and always of a brightness which puts it in a different class from the safe but dull German horn-playing – verged on the miraculous.” 1951: “It is difficult to say anything of Dennis Brain’s performance, except that he was an alchemist, turning copper into gold. Anyone who plays the horn at all is to be honoured, but when a phenomenon like Brain appears, whose artistic and technical capacities seem limitless, one can only write (like Haydn) ‘Laus Deo’.”

His Midas touch extended as far as the Himalayas in 1953, where James Morris was covering the British ascent of Everest for The Times. “Marching through Sherpa country,” Morris subsequently recorded, “it did not in the least surprise me listening on the radio one day to Dennis Brain playing a Mozart horn concerto to find a whole posse of film men bursting through the tent flap to hear him too.” The day the news reached London that Everest had been conquered, Brain was playing in Westminster Abbey at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

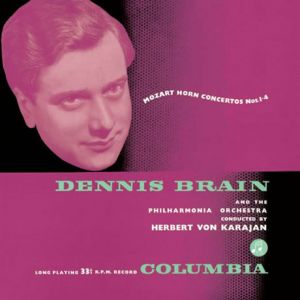

His other interest was in cars. When he recorded the Mozart concertos with Karajan (original LP sleeve, right) he played from memory and, instead of the sheet music, had a copy of Autocar on his music stand. He was the only member of the Philharmonia whom Karajan, also a lover of cars, addressed by his Christian name. In one recording Brain split the opening note. Karajan put down his baton and quietly gave thanks to God. The prodigy was human after all.

Brain was a slave to his own genius. He was in such heavy demand that he missed his father’s funeral in 1955. He also expedited his own. His addiction to speed was no doubt of a piece with the tolerance of risk which helped to make him the ideal horn player. The Philharmonia played three concerts at the Edinburgh Festival on the last three days of August in 1957. Brain fell asleep at the rehearsal for the first of them. During a break in rehearsal on the morning of the third concert, he approached Eugene Ormandy to discuss Strauss’s second horn concerto, which he was due to play in Edinburgh the following Friday. He was planning to spend the week in London. The conductor couldn’t help but notice how shattered he looked, and urged him to slow down. Brain smiled and shrugged. He did a lecture-recital that afternoon and fitted in a catnap before the concert.

On the Monday morning news broke of Brain’s death. At the Prom in the Albert Hall that evening, the audience was asked not to applaud the Royal Philharmonic’s performance of Tchaikovsky’s Sixth, which Brain had played only 48 hours earlier in Edinburgh. At the festival on the Friday, when Brain should have played Strauss 2, they scheduled instead a performance of Schubert’s "Unfinished" Symphony. For his own memorial, Britten turned to the sixth poem of the Serenade for tenor, horn and strings he wrote for Brain, where the horn is silent as the soloist walks into the wings.

I have in my hands the horn of Dennis Brain. His single B flat Alexander. The horn mangled in the car crash. The horn on which he recorded the Mozart concertos with Karajan, which he is playing on the cover of the album (pictured left) I was given for Christmas at the age of 10. I have spent much of my year as a horn player feeling like an impostor, but this moment really caps it.

I have in my hands the horn of Dennis Brain. His single B flat Alexander. The horn mangled in the car crash. The horn on which he recorded the Mozart concertos with Karajan, which he is playing on the cover of the album (pictured left) I was given for Christmas at the age of 10. I have spent much of my year as a horn player feeling like an impostor, but this moment really caps it.

Photographs exist of the instrument when it was retrieved from the wreckage of Brain’s Triumph. The damage seems irreparable. The horn has nonetheless been repaired. I scour the bell and the main tubing for evidence of the accident. If you hold it to the light, tiny interruptions of the smooth surface can just about be discerned. Otherwise the restoration is astonishing.

My companion this morning is Andrew Clark, the principal horn of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, which performs on period instruments. One of the world’s great natural horn players, Andrew happens to be the owner of Dennis Brain’s other instrument, a French piston-valve horn in F made in 1818 by Raoux, a firm of horn manufacturers established in Paris in the 18th century. It was made a decade before the invention of valves, so it was of course a natural horn. Detachable valves were added in the early part of the 20th century, some time before it was presented to Dennis as a student by his father Aubrey.

Horn players are practical, often unsentimental types, and none, it seems, more than Andrew. “I was tipped off by a colleague that the Raoux was going to be for sale. I know some would be interested in it because of its provenance, but I was more interested in it because I thought it would be a good natural horn.”

Dennis Brain switched from the thinner sweeter sound of the Raoux to the more robust German sound of the Alexander in the early 1950s. In the Royal Academy of Music's display case it has been temporarily displaced by an exhibition of Scottish violins, so I have asked if I can see it. We are wearing white gloves to keep our paw prints from sullying the holy relic. Andrew - studious, bespectacled and extremely knowledgeable – starts to talk in great depth about the reconstructed instrument I turn over in my hands. As he talks his gloved forefinger points to various features – the thickness of the metal, the extra tubing to put the instrument into the key of A, the old-fashioned water key. He talks about the gusset, the pretty, the chemise, the sleeve, the bore, the mouthpiece, the sharp angle of the curve, the silver nickel guard around the hoop, the lead-pipe. The lead-pipe is the straight stem into which the mouthpiece is inserted.

“A lot of discussion went on as to how to repair it,” he says. “One of the things that the repairman wanted to do - because it’s standard practice - is replace the lead-pipe, but Mrs Brain was very keen that the instrument should not have replacement parts if at all possible. That’s very interesting because the lead-pipe is a customised version for Dennis Brain. He wanted it to feel more like the old-fashioned piston horn, which has a narrower bore. It should make the sound more contained, a bit smaller. Dennis Brain was never known for being the biggest blower in London. He was known for his lightness of touch and his accuracy and his musicality.”

It’s time for someone to play it. I hand the horn over. Andrew tests the valves, which have not been oiled, and declares them noisy. “If you waggle the bearing from side to side the rotor is not a good fit in there. It’s worn for one reason or another. It may be that the rotor got squashed. I don’t expect this horn to play as well as it did when it was first made.” With that disclaimer, Andrew inserts a mouthpiece into the lead-pipe, raises the instrument, and blows. A flurry of scales and arpeggios rushes out of the bell. It sounds splendid to me. He stops and looks quizzically at the horn.

“What do you think?”

“It feels slightly like a leaky instrument to me. It’s all right.”

He is making an effort to sound undisappointed. “For me it’s a slightly old horn. I’d probably say. ‘Let’s replace the first valve’ but obviously that’s never going to happen. It’s got a brighter sound than I expected. Alexanders are known for being quite bright but not quite as bright as that. But it feels like it would be a nice responsive instrument.”

He hands the horn back. It’s my turn to play Dennis Brain’s beautifully restored single B flat Alexander, perhaps the most illustrious wind instrument in the world. I am, it goes without saying, not worthy. It should be someone else doing this. But I am here and there will never be another chance. I take the thin sharp mouthpiece out of the horn case, attach it to the lead-pipe, and lift the horn towards my lips. I am struck by how light it is, and say so.

“You’ve got that old Lídl, haven’t you?” says Andrew.

The thing about the old Lídl is I’m used to it. I’m a bit thrown by the fact that the horn stands in B flat. My double horn stands in F and is put into B flat by pressing down what Americans call the trigger, or thumb valve. I have a go at the Romanze. It’s a bit of a botched job. Absurdly I can’t remember the fingering. I try the Rondo instead. It doesn’t sound much better. Unlike Andrew, who has extracted a very presentable sound from it, I can’t blame the air leaking out of the valves. I can only blame myself.

This is as good a practical demonstration as could ever be staged that when it comes to horns, the sound is made not by the instrument. It’s made by the person holding the instrument. And the person holding the horn is in the grip of a severe dose of vertigo.

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Goldberg Variations, Ólafsson, Wigmore Hall review - Bach in the shadow of Beethoven

Late changes, and new dramas, from the Icelandic superstar

Goldberg Variations, Ólafsson, Wigmore Hall review - Bach in the shadow of Beethoven

Late changes, and new dramas, from the Icelandic superstar

Mahler's Ninth, BBC Philharmonic, Gamzou, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - vision and intensity

A composer-conductor interprets the last completed symphony in breathtaking style

Mahler's Ninth, BBC Philharmonic, Gamzou, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - vision and intensity

A composer-conductor interprets the last completed symphony in breathtaking style

St Matthew Passion, Dunedin Consort, Butt, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - life, meaning and depth

Annual Scottish airing is crowned by grounded conducting and Ashley Riches’ Christ

St Matthew Passion, Dunedin Consort, Butt, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - life, meaning and depth

Annual Scottish airing is crowned by grounded conducting and Ashley Riches’ Christ

St Matthew Passion, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin review - the heights rescaled

Helen Charlston and Nicholas Mulroy join the lineup in the best Bach anywhere

St Matthew Passion, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin review - the heights rescaled

Helen Charlston and Nicholas Mulroy join the lineup in the best Bach anywhere

Kraggerud, Irish Chamber Orchestra, RIAM Dublin review - stomping, dancing, magical Vivaldi plus

Norwegian violinist and composer gives a perfect programme with vivacious accomplices

Kraggerud, Irish Chamber Orchestra, RIAM Dublin review - stomping, dancing, magical Vivaldi plus

Norwegian violinist and composer gives a perfect programme with vivacious accomplices

Small, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - return to Shostakovich’s ambiguous triumphalism

Illumination from a conductor with his own signature

Small, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - return to Shostakovich’s ambiguous triumphalism

Illumination from a conductor with his own signature

LSO, Noseda, Barbican review - Half Six shake-up

Principal guest conductor is adrenalin-charged in presentation of a Prokofiev monster

LSO, Noseda, Barbican review - Half Six shake-up

Principal guest conductor is adrenalin-charged in presentation of a Prokofiev monster

Frang, LPO, Jurowski, RFH review - every beauty revealed

Schumann rarity equals Beethoven and Schubert in perfectly executed programme

Frang, LPO, Jurowski, RFH review - every beauty revealed

Schumann rarity equals Beethoven and Schubert in perfectly executed programme

Levit, Sternath, Wigmore Hall review - pushing the boundaries in Prokofiev and Shostakovich

Master pianist shines the spotlight on star protégé in another unique programme

Levit, Sternath, Wigmore Hall review - pushing the boundaries in Prokofiev and Shostakovich

Master pianist shines the spotlight on star protégé in another unique programme

Classical CDs: Big bands, beasts and birdcalls

Italian songs, Viennese chamber music and an enterprising guitar quartet

Classical CDs: Big bands, beasts and birdcalls

Italian songs, Viennese chamber music and an enterprising guitar quartet

Connolly, BBC Philharmonic, Paterson, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a journey through French splendours

Magic in lesser-known works of Duruflé and Chausson

Connolly, BBC Philharmonic, Paterson, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a journey through French splendours

Magic in lesser-known works of Duruflé and Chausson

Biss, National Symphony Orchestra, Kuokman, NCH Dublin review - full house goes wild for vivid epics

Passionate and precise playing of Brahms and Berlioz under a dancing master

Biss, National Symphony Orchestra, Kuokman, NCH Dublin review - full house goes wild for vivid epics

Passionate and precise playing of Brahms and Berlioz under a dancing master

Comments

...

Very nice article. In point

I have an alex 90 also, and

I have an alex 90 also, and asked alexander to make a narrow bore leadpipe for my 90. they did and sent it to pope to install. it plays much better now, partially because the old one was super leaky. but the narrow bore isn't stuffy at all. lovely pure tone. must play with a funnel type mouthpiece to get that brain sound as a cupped mouthpiece is a bit harsh