Illuminations, Tynan, Aurora Orchestra, Collon, Snape Maltings | reviews, news & interviews

Illuminations, Tynan, Aurora Orchestra, Collon, Snape Maltings

Illuminations, Tynan, Aurora Orchestra, Collon, Snape Maltings

Aldeburgh Festival opens with a ravishing night of music and physical theatre

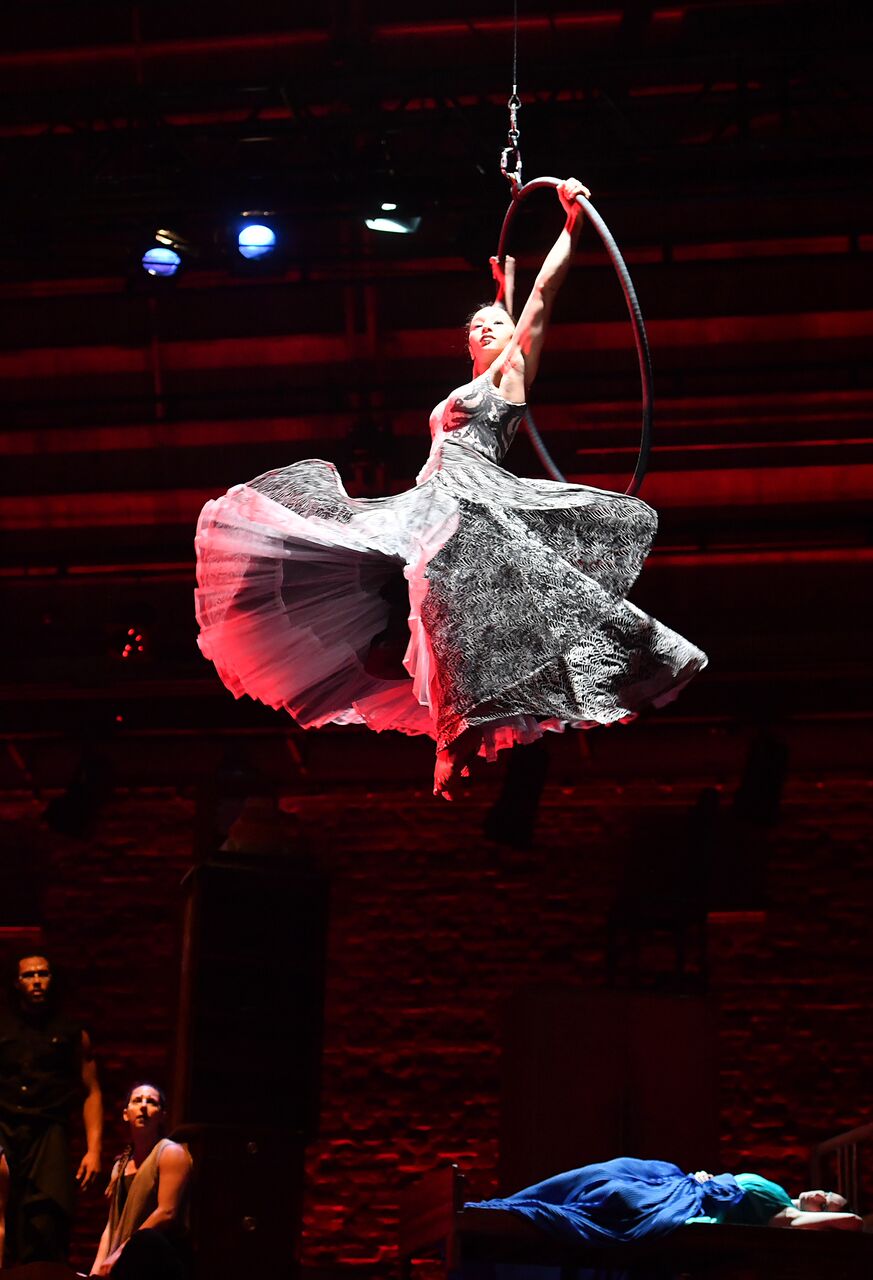

Nothing galvanises an audience quite like physical risk. As soprano Sarah Tynan rose on a hoop into the darkness, intoning the final words of "Départ" from Britten's song cycle Les Illuminations, you could almost hear her heart race. Beneath, a troupe of circus performers held the rope – and her life – in their hands.

In choreographer/director Struan Leslie’s vision, performers decked out as Rimbaud’s "sturdy rogues" brought sinew, grace and heart-stopping spectacle to a night illuminated by explosive, raw-fresh string music: it was all about the vertical.

For Leslie, Rimbaud’s Les Illuminations belong to dream and desire: in a set designed by Gary McCann, lit by Chris Davey, Tynan (pictured right with acrobats) lay in a precariously balanced bed atop a wardrobe, a bedroom where furniture had elongated into skyscrapers, as if seen through a distorting mirror. Beneath her the Aurora Orchestra’s strings subtly shifted and regrouped for different pieces, like a "shoal of shining fish" in conductor Nick Collon’s phrase. Circus performers inhabited the air between on trapeze, hoop and straps, at one point hovering over the sleeping Tynan to lift her from the bed in an airborne erotic caress of mesmerising tenderness.

For Leslie, Rimbaud’s Les Illuminations belong to dream and desire: in a set designed by Gary McCann, lit by Chris Davey, Tynan (pictured right with acrobats) lay in a precariously balanced bed atop a wardrobe, a bedroom where furniture had elongated into skyscrapers, as if seen through a distorting mirror. Beneath her the Aurora Orchestra’s strings subtly shifted and regrouped for different pieces, like a "shoal of shining fish" in conductor Nick Collon’s phrase. Circus performers inhabited the air between on trapeze, hoop and straps, at one point hovering over the sleeping Tynan to lift her from the bed in an airborne erotic caress of mesmerising tenderness.

Les Illuminations itself was the culmination of a musical sequence interfused with the spirit of young Britten. His early, all too easily overlooked masterpiece Young Apollo made a jubilant opener, its crazed orgy of scales (ably given by John Reid) complemented by the dizzy twizzling of an acrobat in a high hoop, rather better than the tame hat trick which began it. French poetry unlocked the teenage Britten’s lyric gift, and Debussy’s String Quartet, with its tragic, sensual mystery belonged here. Richard Tognetti’s arrangement for string orchestra threatens at times to drown its lithe arabesques in a sumptuous sheen, but he wisely reduces forces to quartet for the Andantino: an intensity of focus was found by a single performer here, just as the strain of the first violin’s octaves were wonderfully matched in two gymnasts mirroring movement on trapeze.

Not all the choreography captured the delicate precision of Debussy’s score, reminding us that this was not dance, and couldn’t mesh or synch with the music’s trajectories, especially noticeable at the ends of pieces. Adams’s Shaker Loops shares its zinging effervescence with Britten’s early works, and it was a neat trick for two performers to swing gradually out of phase above the strings. But it couldn’t be sustained or developed, and in the end it was the seven players tearing through this high-velocity score with blistering abandon that proved the more compelling sight.

Not all the choreography captured the delicate precision of Debussy’s score, reminding us that this was not dance, and couldn’t mesh or synch with the music’s trajectories, especially noticeable at the ends of pieces. Adams’s Shaker Loops shares its zinging effervescence with Britten’s early works, and it was a neat trick for two performers to swing gradually out of phase above the strings. But it couldn’t be sustained or developed, and in the end it was the seven players tearing through this high-velocity score with blistering abandon that proved the more compelling sight.

Perhaps the most extraordinary moment of the evening came with Britten’s five-minute Reveille (1937). Over a repeated rotation of chords on piano, a violinist literally plays acrobat, while a single, female trapeze artist performed a poignant journey, from trembling fear to airborne mastery, as she wound herself up a double cloud like a human spider, minute calculations of weight, timing and balance, music constructed in air.

Tynan "awoke" at Les Illuminations' heraldic fanfares, filling the hall with a burning luminescence to relate her dreams. Here, the physical theatre was more literal: "Villes" was a boiling mass of human limbs; a sensual, furry-thighed Pan crept around her in "Antique". Most memorable was the glittering silver creature of "Being Beauteous" who appeared to levitate, balancing on one hand, with Rimbaud’s "arms of crystal". Intoxicating stuff: little wonder a double-bassist, instrument in hand, couldn’t resist grabbing one of the staps and whirling into the air.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment