Jeremy Denk, Wigmore Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Jeremy Denk, Wigmore Hall

Jeremy Denk, Wigmore Hall

Panorama of musical history reveals surprising connections

Medieval to Modern – Jeremy Denk’s Wigmore Hall recital took us on a whistle-stop tour of Western music, beginning with Machaut in the mid-14th century and ending with Ligeti at the end of the 20th. The programme was made up of 25 short works, each by a different composer and arranged in broadly chronological order, resulting in a series of startling contrasts, but punctuated with equally surprising, and often very revealing, continuities.

Nothing in the first half, which spanned Machaut to Bach, was actually written for the piano, but Denk was unapologetic, applying a broad, and thoroughly modern technique with plenty of expression. Medieval polyphony began the programme, with Mass movements from Ockeghem and Desprez interspersed with secular songs, from Binchois, Dufay and others. From here, Denk moved into Baroque keyboard music. The polyphony benefited from Denk’s smooth but carefully applied legato to give the impression of vocal lines, while a subtle, expressive rubato brought every nuance of the virginal and harpsichord music to life.

A masterful piano technique, and obviously deep engagement with the construction of these works allowed Denk to clearly project the important contrapuntal lines, the tenor canti firmi singing out through the Mass movements and the crucial bass lines of Scarlatti and Bach always crystal clear. In his opening address, Denk conceded that the historical narrative was far from linear, and the chronology threw up some jarring contrasts; Gesualdo’s O dolce mio Tesoro sounds bizarre in any time, but no more so than when heard directly after a voluntarie by William Byrd. On the other hand, the continuity from Scarlatti’s ebullient Sonata K 545 to Bach’s darker but equally inventive Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue brought out the best in both composers.

The second half was made up almost entirely of music written for the piano, allowing Denk to demonstrate the scope of his pianistic credentials. His solid and very definite touch, often subtle but never ambiguous, brought an emphatic quality to the Classical-era works. That might feel wearing in a standard programme, but it gave the individual movements presented here valuable identity and definition. The Andante of Mozart’s G-Major Piano Sonata, K 283, got the sequence off to an elegant start, but the mood soon turned more caustic with a surprisingly broody and tempestuous reading of Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 10/1 first movement.

The second half was made up almost entirely of music written for the piano, allowing Denk to demonstrate the scope of his pianistic credentials. His solid and very definite touch, often subtle but never ambiguous, brought an emphatic quality to the Classical-era works. That might feel wearing in a standard programme, but it gave the individual movements presented here valuable identity and definition. The Andante of Mozart’s G-Major Piano Sonata, K 283, got the sequence off to an elegant start, but the mood soon turned more caustic with a surprisingly broody and tempestuous reading of Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 10/1 first movement.

Moving into the Romantic era, Denk really found his stride, and the Liebestod was the highlight of the evening, the pianist perfectly gauging Liszt’s take on Wagner to produce colours and textures as nuanced as the original. This was the longest work in the recital, and Denk took the opportunity to sculpt the long paragraphs and carefully grade each of the climaxes. Brahms might seem a comedown after this, but the late Intermezo, op. 119/1, proved the perfect epilogue, admittedly smaller in conception and more interior in its expression, but the harmonies are similarly ambiguous, and the experience, at least of hearing them together here, was one of startling unity.

Up until Stockhausen’s Klavierstück 1, Denk had performed entirely from memory, but could be forgiven for reaching for the music stand now. This short, sharp shock served to contextualise the final phase of the evening, to starkly contrast the Philip Glass that followed on, and to make the Ligeti Étude ‘Automne à Varsovie’ seem like a summation rather than a wayward oddity.

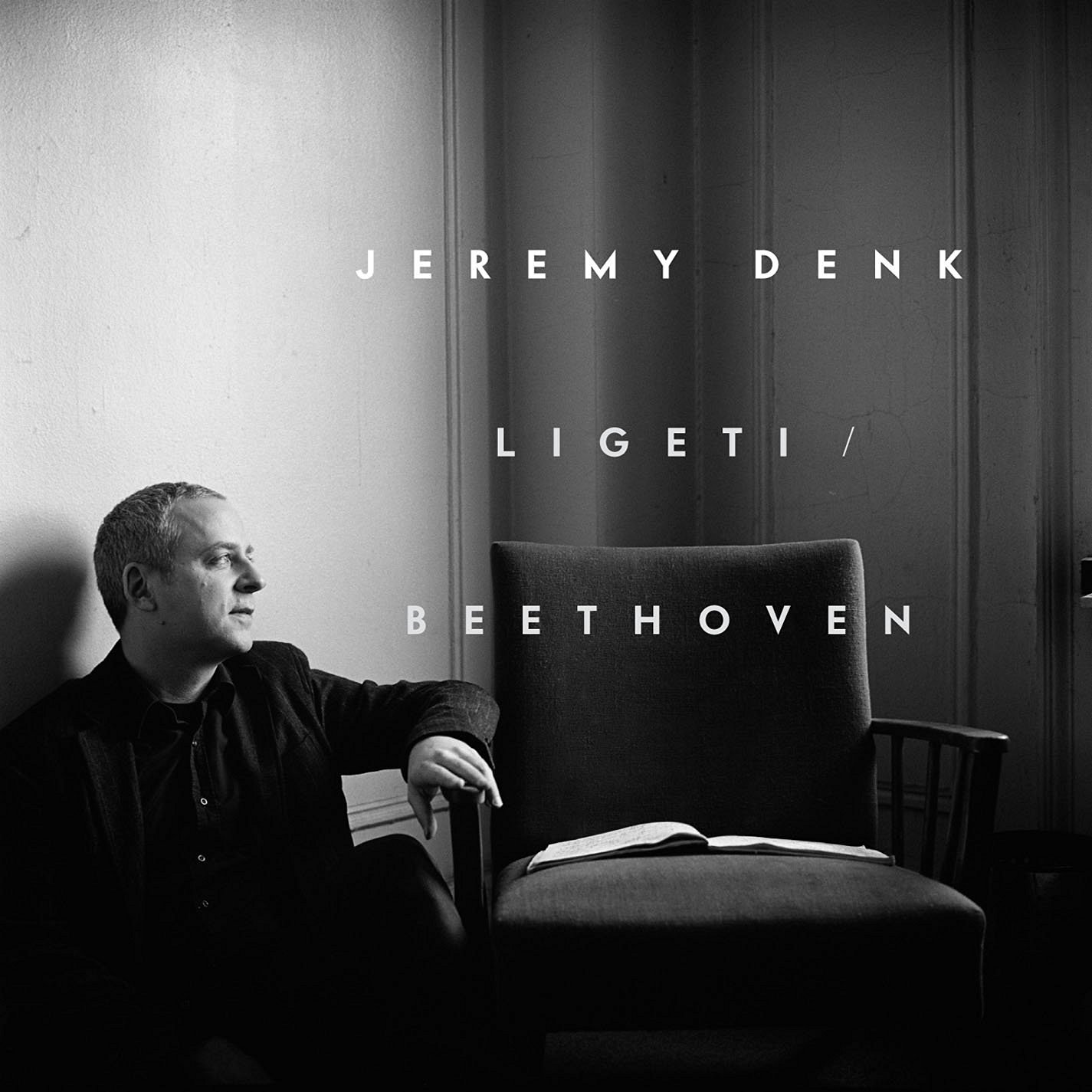

In fact, the Ligeti proved the perfect climax, not least for Denk’s masterful performance (not coincidentally, his recording of the Ligeti Études - pictured right - was on sale in the foyer). Despite the astonishing versatility the pianist had shown throughout the evening, this music remains his forte. As in the Liebestod, the subtle gradations of tone and the fluent but carefully controlled way that each climax was approached marked this out as a distinguished reading, and the thundering descent to the bottom of the keyboard brought the evening to a dramatic and unambiguous close.

In fact, the Ligeti proved the perfect climax, not least for Denk’s masterful performance (not coincidentally, his recording of the Ligeti Études - pictured right - was on sale in the foyer). Despite the astonishing versatility the pianist had shown throughout the evening, this music remains his forte. As in the Liebestod, the subtle gradations of tone and the fluent but carefully controlled way that each climax was approached marked this out as a distinguished reading, and the thundering descent to the bottom of the keyboard brought the evening to a dramatic and unambiguous close.

Apart, that is, from a brief epilogue, a return to the Medieval with the Binchois Triste plaisir that had appeared early in the first half. It brought welcome calm after the Ligeti and offered a moment of reflection to contemplate the programme, a broad and detailed historical panorama in which every one of the works was presented in a new and revealing light.

- This performance was recorded by BBC Radio 3 and will be broadcast on Tuesday 20 September

- Read more classical music reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

London Choral Sinfonia, Waldron, Smith Square Hall review - contemporary choral classics alongside an ambitious premiere

An impassioned response to the climate crisis was slightly hamstrung by its text

London Choral Sinfonia, Waldron, Smith Square Hall review - contemporary choral classics alongside an ambitious premiere

An impassioned response to the climate crisis was slightly hamstrung by its text

Goldberg Variations, Ólafsson, Wigmore Hall review - Bach in the shadow of Beethoven

Late changes, and new dramas, from the Icelandic superstar

Goldberg Variations, Ólafsson, Wigmore Hall review - Bach in the shadow of Beethoven

Late changes, and new dramas, from the Icelandic superstar

Mahler's Ninth, BBC Philharmonic, Gamzou, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - vision and intensity

A composer-conductor interprets the last completed symphony in breathtaking style

Mahler's Ninth, BBC Philharmonic, Gamzou, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - vision and intensity

A composer-conductor interprets the last completed symphony in breathtaking style

St Matthew Passion, Dunedin Consort, Butt, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - life, meaning and depth

Annual Scottish airing is crowned by grounded conducting and Ashley Riches’ Christ

St Matthew Passion, Dunedin Consort, Butt, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - life, meaning and depth

Annual Scottish airing is crowned by grounded conducting and Ashley Riches’ Christ

St Matthew Passion, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin review - the heights rescaled

Helen Charlston and Nicholas Mulroy join the lineup in the best Bach anywhere

St Matthew Passion, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin review - the heights rescaled

Helen Charlston and Nicholas Mulroy join the lineup in the best Bach anywhere

Kraggerud, Irish Chamber Orchestra, RIAM Dublin review - stomping, dancing, magical Vivaldi plus

Norwegian violinist and composer gives a perfect programme with vivacious accomplices

Kraggerud, Irish Chamber Orchestra, RIAM Dublin review - stomping, dancing, magical Vivaldi plus

Norwegian violinist and composer gives a perfect programme with vivacious accomplices

Small, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - return to Shostakovich’s ambiguous triumphalism

Illumination from a conductor with his own signature

Small, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - return to Shostakovich’s ambiguous triumphalism

Illumination from a conductor with his own signature

LSO, Noseda, Barbican review - Half Six shake-up

Principal guest conductor is adrenalin-charged in presentation of a Prokofiev monster

LSO, Noseda, Barbican review - Half Six shake-up

Principal guest conductor is adrenalin-charged in presentation of a Prokofiev monster

Frang, LPO, Jurowski, RFH review - every beauty revealed

Schumann rarity equals Beethoven and Schubert in perfectly executed programme

Frang, LPO, Jurowski, RFH review - every beauty revealed

Schumann rarity equals Beethoven and Schubert in perfectly executed programme

Levit, Sternath, Wigmore Hall review - pushing the boundaries in Prokofiev and Shostakovich

Master pianist shines the spotlight on star protégé in another unique programme

Levit, Sternath, Wigmore Hall review - pushing the boundaries in Prokofiev and Shostakovich

Master pianist shines the spotlight on star protégé in another unique programme

Classical CDs: Big bands, beasts and birdcalls

Italian songs, Viennese chamber music and an enterprising guitar quartet

Classical CDs: Big bands, beasts and birdcalls

Italian songs, Viennese chamber music and an enterprising guitar quartet

Connolly, BBC Philharmonic, Paterson, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a journey through French splendours

Magic in lesser-known works of Duruflé and Chausson

Connolly, BBC Philharmonic, Paterson, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a journey through French splendours

Magic in lesser-known works of Duruflé and Chausson

Add comment