Remembering Tavener | reviews, news & interviews

Remembering Tavener

Remembering Tavener

Two singers, a cellist and a conductor commemorate a master of musical spirituality

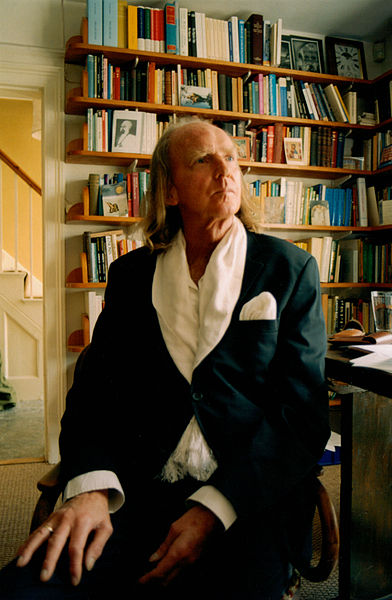

You may have noticed an unholy silence from theartsdesk in the immediate aftermath of Sir John Tavener’s death a week ago today, just under three months short of his 70th birthday. Three of us in the classical team felt we just didn’t know his music well enough in the round, or care enough, to give an authoritative judgement.

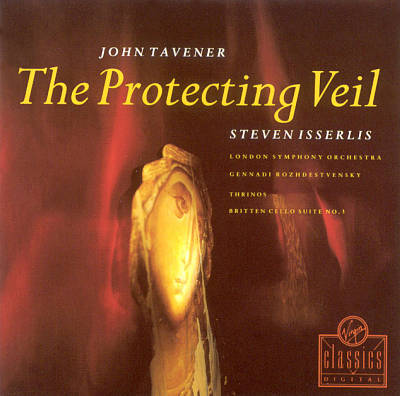

There were the early achievements – his trailblazing 1968 cantata The Whale, for instance – and then what felt like an increasing law of diminishing musical returns as Tavener took up the mantle of the Russian Orthodox Church. What ideas there were seemed spread thin over a large canvas. I more or less gave up after hearing The Akathist of Thanksgiving live in 1987: what was there here that I couldn’t get from a standard traditional service done at the highest level? Wasn’t a composer who took on another religion merely wearing its coat? Yet that same year also saw the creation of a masterpiece, The Protecting Veil, for cello and strings. However one felt about what fellow composer James MacMillan has criticised as the "instant spiritual high" of such music, this work certainly cast its spell.

Sure enough, Tavener did cast off Orthodoxy, musically though not personally, feeling that it had restricted his style, and subsequently drew on the music of other religions, but I still drew a blank on the larger-scale pieces. But there’s no doubting the effectiveness of the shorter choral anthems. On two successive Christmas services at St Paul’s Cathedral we in the congregation were blitzed by the sudden chord of light that pierces God is with us. Song for Athene caught the imagination of a worldwide public at Diana’s funeral.

Sure enough, Tavener did cast off Orthodoxy, musically though not personally, feeling that it had restricted his style, and subsequently drew on the music of other religions, but I still drew a blank on the larger-scale pieces. But there’s no doubting the effectiveness of the shorter choral anthems. On two successive Christmas services at St Paul’s Cathedral we in the congregation were blitzed by the sudden chord of light that pierces God is with us. Song for Athene caught the imagination of a worldwide public at Diana’s funeral.

Even so, it seemed best to leave the tributes to those outstanding musicians who knew and worked with him. Soprano Patricia Rozario, cellist Steven Isserlis, countertenor Iestyn Davies and conductor of The Tallis Scholars Peter Phillips pay eloquent homage.

PATRICIA ROZARIO

John Tavener was rather an enigma. He immersed himself in all things spiritual, spent a lot of time learning and appreciating other religions, wrote music that was powerfully spiritual and uplifted the soul of the listener. Yet he also loved the finer things of life like good food and wines, fast cars and smart clothes. I was very lucky to be invited to audition for the title role of his opera Mary of Egypt in 1991 and was terrified at having to sight read his music from the manuscript.

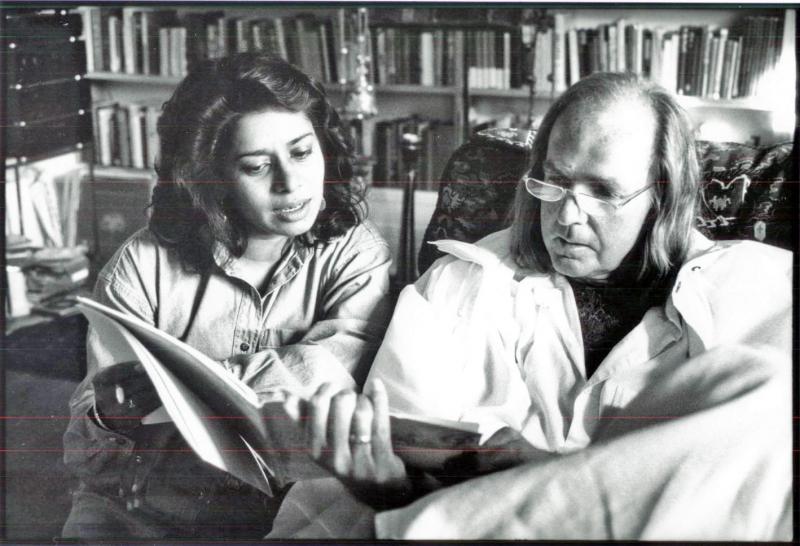

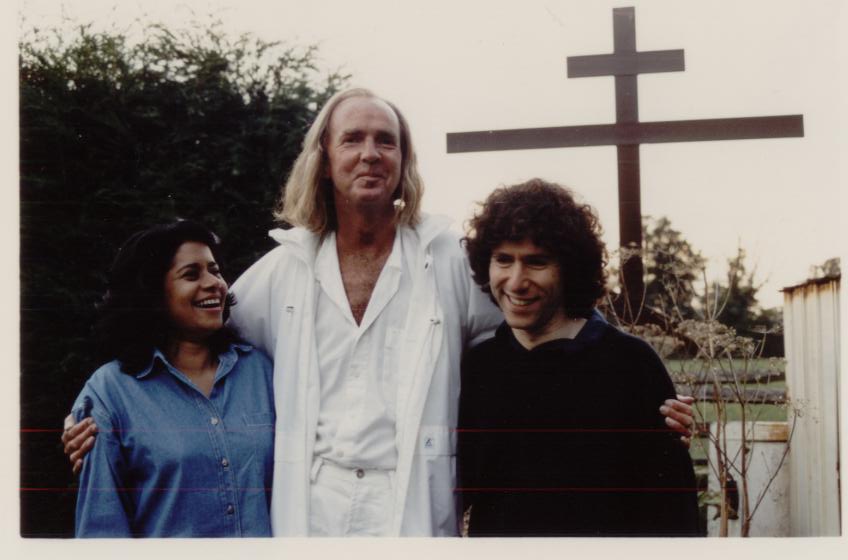

After the first performance at Aldeburgh in 1992, John came backstage and said he wanted me to perform and record all his music! I was amazed by his confidence in me and was delighted when he presented me, several months later, with the Akhmatova Songs written specially for me and his favourite cellist Steven Isserlis (the three pictured above).

After the first performance at Aldeburgh in 1992, John came backstage and said he wanted me to perform and record all his music! I was amazed by his confidence in me and was delighted when he presented me, several months later, with the Akhmatova Songs written specially for me and his favourite cellist Steven Isserlis (the three pictured above).

John developed a unique sound world that in his large dramatic works or in the more delicate ones is immediately recognizable as his. He has left a wealth of amazingly beautiful choral works which will be performed and loved by people all over the world.

Working with John was very intense and the more works he wrote for my voice the greater the challenge became, requiring great technical skill and stamina. Song of the Angel, Agraphon - containing elements of Indian music which took me back to my roots – Iero Oniro, The World and Schuon Lieder are very special to me. John had a great sense of humour and loved gathering his friends and family around him. I shall miss him greatly.

STEVEN ISSERLIS

I first met John Tavener in the late 1980s, when I asked him to write a work for me; this became The Protecting Veil. From then on, we remained close friends and collaborators. He was to write several more pieces for me. Sviyati was written to be played with a Georgian choir at the Cricklade Festival in Wlitshire, where I was artistic advisor, he patron. John composed Chant for solo cello on a whim after he overheard the music from a Jewish wedding in the distance. There were also Thrinos for solo cello, also (as I remember) written spontaneously, after the premiere of The Protecting Veil; and more recently, The Death of Ivan Ilyich for bass-baritone, cello and orchestra, based on the Tolstoy novella about a man who finds peace from his sufferings just before death overtakes him. This was the first major piece John had written since his massive heart attack in 2007, and he identified deeply with its subject matter; it is a powerful, searing work. He was also about to embark on a new piece for me – perhaps based around Schumann – when death so unexpectedly overtook him.

I first met John Tavener in the late 1980s, when I asked him to write a work for me; this became The Protecting Veil. From then on, we remained close friends and collaborators. He was to write several more pieces for me. Sviyati was written to be played with a Georgian choir at the Cricklade Festival in Wlitshire, where I was artistic advisor, he patron. John composed Chant for solo cello on a whim after he overheard the music from a Jewish wedding in the distance. There were also Thrinos for solo cello, also (as I remember) written spontaneously, after the premiere of The Protecting Veil; and more recently, The Death of Ivan Ilyich for bass-baritone, cello and orchestra, based on the Tolstoy novella about a man who finds peace from his sufferings just before death overtakes him. This was the first major piece John had written since his massive heart attack in 2007, and he identified deeply with its subject matter; it is a powerful, searing work. He was also about to embark on a new piece for me – perhaps based around Schumann – when death so unexpectedly overtook him.

So we worked together a lot over the 25 years. But it was more than just a working relationship: it was a friendship. John was complicated, and could be very difficult; but it was impossible not to care about him. Illness mellowed him, without changing his essence. It's when someone has gone that you realise just how much they meant to you. John's departure leaves a huge hole - I can't stop thinking about him. I'm sure I'm not alone in that - all of his friends must feel that way. It's true that he suffered horribly in the last few years; but he seemed to be more at peace nevertheless, and happier with his family than I'd ever seen him. I suppose it wasn't unexpected that he would go so suddenly, but the shock was - and is - intense. His life-force was still so strong.

IESTYN DAVIES

In a year replete with the music of Benjamin Britten, which I had so thoroughly enjoyed singing as a treble chorister in the choir of St John’s College Cambridge, I was similarly thrown into a lapse of nostalgia upon hearing of the death last week of John Tavener. Like Britten’s, his choral music stood out amongst the diet of bluesy, melancholic Howells, pastoral Finzi and moustached Elgar and Stanford. To see The Lamb or Song for Athene on the service list was reason enough for that day’s evensong to go up in our estimations. Similarly the Hymn to the Mother of God, simple yet to be sung with “a Sense of Awesome Majesty and Splendour", never failed to excite the child in us all as choristers who loved the Mass settings of Langlais and Vierne for their crashing organ accompaniments.

In a year replete with the music of Benjamin Britten, which I had so thoroughly enjoyed singing as a treble chorister in the choir of St John’s College Cambridge, I was similarly thrown into a lapse of nostalgia upon hearing of the death last week of John Tavener. Like Britten’s, his choral music stood out amongst the diet of bluesy, melancholic Howells, pastoral Finzi and moustached Elgar and Stanford. To see The Lamb or Song for Athene on the service list was reason enough for that day’s evensong to go up in our estimations. Similarly the Hymn to the Mother of God, simple yet to be sung with “a Sense of Awesome Majesty and Splendour", never failed to excite the child in us all as choristers who loved the Mass settings of Langlais and Vierne for their crashing organ accompaniments.

So full is this output of incredible tunes, or "ear worms" as they are increasingly dubbed now, arresting harmonic shifts and very, very simple structures, that only a fool would hide it away from young, intelligent minds eager to sing their hearts out. Veiled though it was in the wafts of Russian Orthodoxy Tavener’s choral music had a truly Anglican sensitivity that seemed to embrace the spirituality of that dark, ancient and collegiate tradition of Evensong and thus became a fantastically significant part of my own musical upbringing.

He was kind, gracious and patient with his thoughts and words and at some point he was permitted to conduct one take for the cameras of The Lamb. His arms extended beyond belief and he drew the most elongated beats through the air as if drawing back the heaviest of curtains; from his finger-tips we seemed to feel a very different energy to that which we were so used, and the simplest of pieces became filled with a strange and new vitality. As boys do, we filed up to him for autographs, signing our gold embossed folders of course and mine still sits at home now as a reminder of that occasion.

I was to be part of a Tavener experience once more a decade later whilst a member of the Temple Church Choir in London. On a different scale, far removed from the miniatures (in comparison) of my time as a treble. His epic cycle The Veil of the Temple lasted around seven hours and together with the Holst Singers our choir battled a form of jetlag to bring this epic work through to sunrise. Tavener declared of the work: “It is composed in eight cycles like a gigantic prayer wheel with each cycle ascending in pitch and in cycles 1 to 7 using verses from St. John’s Gospel at the centre.”

What Tavener hoped was that the journey for both the musicians and the listeners present would lead them to "some kind of spiritual peak of intensity" – in doing so he wanted to illustrate the underlying brotherhood of all religions beneath their outward form. Transcendental shape was achieved by minimalistic repetition of themes throughout the evening on an almost meditative plane, a style of Tavener’s throughout his choral music exhibited here on a considerably magisterial scale. It was an awesome underlining of the aphorism "less is more" if ever there was one! Repeated in New York at the Lincoln Centre it remains one of the most memorable (and longest) musical experiences in which I have taken part.

What Tavener hoped was that the journey for both the musicians and the listeners present would lead them to "some kind of spiritual peak of intensity" – in doing so he wanted to illustrate the underlying brotherhood of all religions beneath their outward form. Transcendental shape was achieved by minimalistic repetition of themes throughout the evening on an almost meditative plane, a style of Tavener’s throughout his choral music exhibited here on a considerably magisterial scale. It was an awesome underlining of the aphorism "less is more" if ever there was one! Repeated in New York at the Lincoln Centre it remains one of the most memorable (and longest) musical experiences in which I have taken part.

When asked to talk about the choral music of John Tavener though, it is hard not to revert to the cliché that the music rather speaks for itself. Any attempt to analyse, scrutinize, pull apart, critique or question his music reduces the experience of singing it and being part of performances of it – something that is much harder to put into words. Thankfully I have a CD to hand of his great choral works recorded at St John’s for Naxos with which to reflect and remind me of his mysteriously enchanting music that was hair pulling in its simplicity yet wholly original and inspiring. John Tavener’s own performance directions seem to always sum up best: “as slow as possible; serene, tender, beyond time, beyond being.”

PETER PHILLIPS

John Tavener's death has not come as a surprise to his friends and family. It was well known that he was suffering from an hereditary heart complaint, and that it was only a matter of time: his younger brother, Roger, had pre-deceased him a while ago. So every day one could still get in touch with John seemed like a blessing, and although latterly he was in constant pain I discovered that his interest in the processes of composition was continuing unabated.

John Tavener's death has not come as a surprise to his friends and family. It was well known that he was suffering from an hereditary heart complaint, and that it was only a matter of time: his younger brother, Roger, had pre-deceased him a while ago. So every day one could still get in touch with John seemed like a blessing, and although latterly he was in constant pain I discovered that his interest in the processes of composition was continuing unabated.

The last time I saw him he had asked me to bring the score of Josquin's 24-voice canon Qui habitat. He already had a recording; and so we passed the afternoon listening to this monumental masterpiece on a loop. Of course I wondered what would come of it. Back in the 1980s he had written a double-choir canon as part of the Ikon of Light, but I wasn't aware that he had maintained his technique in this most mathematical of all compositional devices. Nonetheless, some weeks later, he announced that he had written a Requiem (called the Requiem Fragments) for me to premiere next year, as part of the celebrations for his 70th birthday, which will fall in January. Just last Tuesday morning I decided to explore that score for the first time – and discovered that the last movement is a triple-choir canon of the utmost complexity.

He would have enjoyed the fact that at the moment I was coming to grips with a composition which may be accounted his swansong – music which shows his powers not only to be undiminished but extended – he died. He believed in fateful happenings and he liked miracles. The first performance of this Requiem should be a poignant occasion.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

Comments

David this is brilliantly

David this is brilliantly put-together. It has been fascinating to read such considered reactions from people with a strong and genuine connection to Tavener.

Such pieces are definitely worth waiting for, rather than the now-conventional emoting of pieces written under time-pressure immediately when sad news breaks.

Chapeau to you, and a big thank you from me for such heart-felt and informative tributes to all three contributors. .