The astronomer Sir Patrick Moore was a keen composer of decided musical preferences, and no mean xylophonist. The news of his death on Sunday reminded me of my hugely enjoyable encounter with him - for musical reasons - for the Daily Telegraph in October 1998, heralding the release of a recording of his tunes.

PATRICK Moore is hammering the living daylights out of the xylophone in his dark, cluttered drawing-room. Over it hangs a sharp message to visitors: "No, you may NOT put your cup on the xylophone". I have a sudden vision of him attacking an offender with his mallets.

When I arrived at his house in the clear-skied, seaside Sussex village of Selsey to interview him about the first CD of his musical compositions (to be released by Cavendish next month), I had asked him if he would play. He hoists himself up obligingly, and gets thoroughly waylaid trying to set up his accompaniment tape.

"Should have sorted this out," he grumbles, the familiar Churchillian face scowling, monocle gripped in the right eye, the body arrestingly large in its roomy black suit. But he has been in hospital, he says, hence the disorganisation.

Tension steadily mounts as the recalcitrant cassette-player disgorges first a snatch of orchestral waltz, then a bar-room piano. "Oh no, I hate tapes," wails Moore. But persistence wins the day, and at last he has the tape machine running, and is battering on the wooden keys, faster and faster, leaving the faint, tinny band far behind.

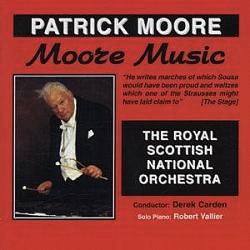

Moore, as all viewers of The Sky at Night know, is an innately funny man - both boffin and buffoon. Here is the man who commentated on the moon landings, who mapped the moon for NASA and who has an asteroid named after him, playing "Penguin Parade" and thrilling at critical tributes such as: "He writes marches of which Sousa would have been proud". Three days after my visit, Moore is due to start recording his CD, on which he will play the xylophone.

"Yes, but I don't want to play it. I am a composer, not a performer," he says regally. The Royal Scottish National Orchestra are recording the works, including the "Woodland Suite", in which "the first movement was written when I was 13, the second when I was 71, and you cannot tell the difference." He heaves with hilarity: "You cannot tell the difference..."

Isn't that rather odd? Haven't his musical tastes changed at all? "No, never did." He avoided jazz, preferred the Strausses, Gilbert and Sullivan and Sousa.

What about the Beatles? "Oh, I remember having a drink with the Beatles when they were starting out. I don't like their music. The music I like, and like to write, belongs not to 1998 but to 1898. I'm open about that."

Well, I try, what about modern composers? "Oh, Chopin, Grieg, Rachmaninov, I love. I went to a Prom two years ago and there was a very modern piece of music on that sounded exactly like a cat-fight. Birtwistle. That's who it was. Not difficult but impossible. I can't make head nor tail of it." He juts out his chin, and his monocle falls out.

"I find it quite fun that I've been recognised as a serious composer, which apparently I am now." He has written 70 pieces, having taught himself to read music from a Strauss waltz.

"One thing I could do - and it's no credit to me, don't get me wrong - that weird thing called perfect pitch and perfect time I have got. No credit to me. I've found my first composition the other day too. Made when I was 10. Waltzes, I love 'em."

He jumps to his piano (out of tune) and plays a respectably advanced waltz with an oompah bass and a twiddly melody. I am impressed.

He jumps to his piano (out of tune) and plays a respectably advanced waltz with an oompah bass and a twiddly melody. I am impressed.

"Are you a waltzer?" I ask. He sighs, gulps air fishily: "Definitely not. I am not a dancer", and giggles manically.

He writes his astronomy books very fast, clattering them out with two fingers on his 1908 typewriter (a gorgeous, rococo instrument infinitely more pleasing than the flat grey computer near it). "I can type accurately on it at 90 words a minute. Whereas on the computer I can barely make 15."

Tunes come with more difficulty - "I can get completely stuck," he says. His work is deceptively titled. His three operas are Galileo - the True Story, Theseus and Perseus. I ponderously inquire whether the choice of subjects is related to astronomy at all.

Moore hands me an elderly sheaf of closely typed thin paper. "There's the libretto of Perseus." I find that the hero's first song is called, "Please don't call me Percy".

Moore shouts, "Perseus is a bad-tempered old bore who once killed a Gorgon by mistake, and now has to face the real thing."

Was Theseus inspired by Richard Strauss's opera Ariadne auf Naxos? "Oh no, once again it's mythology. As you know, the Minotaur is a kittenish little creature that likes biscuits, and the entire thing is a put-up job. Of course Theseus is scared stiff of the Minotaur and doesn't realise it's a fake..."

Not serious opera, then. "Oh, I couldn't write anything serious," he replies. "The only serious thing I did was the 'Nocturne'. And one weird thing... just after my mother died in 1981, I was very close to her, and I'd been asked by the Liverpool Phil to do a tone-poem, 'Phaethon's Ride', the boy who drew the sun chariot. I sat down at the piano there, having had a terrible night up, and I jammed my hand on the tape and just started improvising. And I got it. That piece has been played by symphony orchestras all over the world."

Mrs Moore trained as an opera singer in Italy, before World War I introduced her to her husband, an army officer, and in 1923 she produced their sole child, Patrick, a sickly boy. She put the first book on stars his way.

Immensely proudly, her son produces her own first book - done when she was 87. Mrs Moore in Space is an enchantingly drawn book about humanoid aliens. In one picture, they are racing their bikes round Saturn's rings.

Immensely proudly, her son produces her own first book - done when she was 87. Mrs Moore in Space is an enchantingly drawn book about humanoid aliens. In one picture, they are racing their bikes round Saturn's rings.

"Some of these drawings were done before I was born," he says delightedly. "I was very close to my mother. More so than most. It's no secret at all. My girl was killed in the war. Therefore I didn't marry - there was no one else for me." He and his mother lived together in the house in Selsey.

"You get interviewed constantly. What do we always ask you?"

He recites wearily: "Is there life elsewhere. Are there aliens on Mars. How big is the universe. Oh, the usual."

Has he ever been in a space-ship, my 10-year-old son wants to know.

"I don't think I've ever been asked that. No, I couldn't. For one thing I'm the wrong age. Secondly of course, I'm the wrong nationality. And in any case I'm the wrong medical grade."

His bad heart meant Moore had to turn down his place at Eton and be educated at home; the war stopped him taking up his place at Cambridge. "I didn't get to either!" he says with a strange glee. Had he done so, he would surely have become one of the army of anonymous professional astronomers, instead of the people's star-man on 42 years of The Sky at Night.

Did he envy Neil Armstrong, placing his heavy boot on the object of Moore's lifelong affections? "I'd have liked to have gone there, certainly," he says crisply. There is a large poster of the moon's view of the earth outside his loo.

Where you might expect him to scoff that astronomy has become a number-crunching set of computer physics, rather than the romantic star-gazing of his own youth, he does not.

Astronomy is probably the only science where the amateur can play a useful role, and does

"Oh, it's totally different from when I started. New techniques, new discoveries, now there's space research, of course. But astronomy is probably the only science where the amateur can play a useful role, and does. The amateur knows the sky better than most professionals. I am one of a vanishing race of people who look through telescopes. We can do things that professionals don't want to do or don't have time to do. There are thousands of variable stars in the skies, and amateurs keep watch on them.

"Did you know that in 1933, for example, the white spot on Saturn was discovered by Will Hay, the actor? And now the Reverend Robert Evans, an Australian clergyman, has discovered 25 supernovae in external galaxies and warned the professionals to get onto it. He knows them all off by heart.

"I may say," - he continues, deadpan - "a little while ago, I had a phone call from a very famous astronomer whom I am not going to name; he said he had just discovered a bright nova and was just about to notify the Royal Observatory. He'd made a completely independent discovery of Saturn..."

It's a great story, and he chuckles with palpable glee - old Moore the amateur getting one up on the knighted professional. When his CD comes out, it's a pound to a penny that it outsells Sir Harrison Birtwistle's cat-fights.

- Moore Music was released in 2001

- This piece originally appeared in the Daily Telegraph on 13 October 1998

Listen to Sir Patrick Moore play his own 'Penguin Parade' on the xylophone, with a band arrangement by John Alderton

Add comment