theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Neeme Järvi | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Neeme Järvi

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Neeme Järvi

The master conductor talks about his native Estonia and his vast discography

Honour your senior master conductors: there aren't so many of them left now. Abbado and Haitink spring most readily to mind, but orchestral musicians may also nominate Neeme Järvi, who celebrated his 74th birthday last week. A passionate patriot and the man his country voted "Estonian of the Century" in 2000, he proudly sports the colours of the national flag in concert attire by virtue of a natty added blue handkerchief.

It's also thanks to his boundless enthusiasm for listening to other conductors and passing on his passion that two other Järvis wield the baton - sons Paavo, who told me when I met him that he and his father message each other constantly about other interpretations which have excited them, and the younger Kristjan - while a fourth, their sister Maarika, is a superbly accomplished flautist. Fine as the other conducting Järvis already are, I'll always have an undying loyalty to the patriarch, since he was the first master I ever followed with total devotion as a concert-going student in Edinburgh during the early 1980s, and the first conductor I ever interviewed, for a piece in the student newspaper archly entitled (not by me) "An Estonian with SNO on his boots".

The twilight of Sir Alexander Gibson at the then still plain Scottish National Orchestra would throw up the occasional gem from time to time, but it was Järvi who electrified the players, and everyone felt it. He brought new repertoire - not least the works of his compatriot Arvo Pärt - and their recordings together of Shostakovich and Prokofiev symphonies still remain, in many instances, benchmarks. At the same time he was nurturing his other orchestra, the Gothenburg Symphony (Järvi pictured above outside the Konserthuset in 1982), in Sibelius, Nielsen and lesser masters such as Alfven and Stenhammar to whom he has always been so devoted.

The twilight of Sir Alexander Gibson at the then still plain Scottish National Orchestra would throw up the occasional gem from time to time, but it was Järvi who electrified the players, and everyone felt it. He brought new repertoire - not least the works of his compatriot Arvo Pärt - and their recordings together of Shostakovich and Prokofiev symphonies still remain, in many instances, benchmarks. At the same time he was nurturing his other orchestra, the Gothenburg Symphony (Järvi pictured above outside the Konserthuset in 1982), in Sibelius, Nielsen and lesser masters such as Alfven and Stenhammar to whom he has always been so devoted.

I've met up delightedly with Järvi many times since then, not least on a triumphant but politically awkward return visit to Estonia with the Gothenburgers shortly before the collapse of the Soviet empire. It was with a special emotion that I returned to Edinburgh's Usher Hall earlier this year to see him make his annual appearance with his beloved Scots orchestra. The concert did not disappoint, as you can read in theartsdesk review; nor did our meeting, though I certainly had a sense of déjà vu when the promised slot got eaten up by time needed for the BBC Radio 3 recording, and he characteristically agreed to meet in his dressing room 20 minutes before the concert. We were talking until 7.25pm, when he blithely took his leave to conduct the first-half performance of Dvorak's Serenade for Strings. Inevitably discussion focused on the Shostakovich symphony associated with the siege of Leningrad and, equally inevitably, Järvi managed to connect it in his idiosyncratic but always passionate, tumbling English with another work by one of his favourite Estonians.

DAVID NICE: So what you're saying is that the Leningrad's ideal companion piece is Eduard Tubin's Fifth Symphony?

NEEME JÄRVI: I’d like to play it in concert, not just because it's completely rooted in Estonia but because it's written at the same time. Tubin left Russian-occupied Estonia in 1940. Then the Germans came back, and that was Nazi time until 1945 – Tubin and all Estonians supposed to go to Siberia to die, they all left, lots of people left, Tubin went to Sweden and he wrote all his feelings about what’s happened in Estonia, and it’s a great war symphony. At the same time Shostakovich was inside all this hell and wrote this symphony.

It's going to be 70 years this September since the blockade.

That's my city, you know, I studied in Leningrad, at the Conservatoire where every Russian composer and musician went, and [the greatest of all Russian conductors Yevgeny] Mravinsky was there, and it was a great time of performances by the Leningrad Philharmonic.

You studied at the Conservatoire with Nikolay Rabinovich...

Rabinovich and Mravinsky too, I was a postgraduate student with Mravinsky. I was at all his performances and rehearsals, he gave all the most important first performances there. After him immediately this music came to Tallinn. Roman Matsov conducted the Estonian Radio Symphony Orchestra, which is now the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra [Jarvi was principal conductor from 1963 to 1979, and then returned in 2010, only to leave in protest at state interference in a crucial administrative post. He has also conducted 25,000 singers at the great choral festivals - (pictured above in 2009)]. As a young boy, I was at every performance of every symphony that was performed at that time.

Rabinovich and Mravinsky too, I was a postgraduate student with Mravinsky. I was at all his performances and rehearsals, he gave all the most important first performances there. After him immediately this music came to Tallinn. Roman Matsov conducted the Estonian Radio Symphony Orchestra, which is now the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra [Jarvi was principal conductor from 1963 to 1979, and then returned in 2010, only to leave in protest at state interference in a crucial administrative post. He has also conducted 25,000 singers at the great choral festivals - (pictured above in 2009)]. As a young boy, I was at every performance of every symphony that was performed at that time.

As a child, were you conscious of what was happening in Leningrad – would the siege have impinged, the events of 1941-2? Because you were very young.

I was very young, yes, but politically it was two different worlds. Estonia was a relief after the Germans came in, because Estonia was bombed and suddenly, you know, people didn’t know what to do – escape, or stay there. People who stayed there were sent to Siberia to die in these animal camps... 1945, when Russians came back, that’s tragic. And that’s what Tubin wrote his Fifth Symphony about, but this – and you never know, against what Shostakovich wrote in this work, because there’s a lot of speculation about it – Hitler or Stalin? But both are there.

I think a composer brings all his experience to anything he writes at any time, so having lived through that… it doesn’t have to be about 1937, or 1941, it’s probably about both.

And that is music where – you can say with music a lot of things for which you don’t have words. But if you have words, you’re in trouble. But Shostakovich speculated… wrote all his lifespan for them, because he was a dangerous person for Soviet authorities, he was a non-person, they would love to have killed him - and Prokofiev and Khachaturian in 1947. Khachaturian wrote "The Sabre Dance" - most popular piece - but he was noted as an enemy as a modern musician by the Soviet government. At that time nothing you did was right.

Listen to Järvi conducting the Scottish National Orchestra in the first part of the slow movement from Prokofiev's Sixth Symphony, composed in 1946

Culture is always an obstacle for leaders, our days also, whether you’re in USA or Estonia, they say, cut culture everywhere, we don’t need it. Oh, 30 per cent can be removed, oh very good: out! This is how they’re behaving. What’s Italia doing? Berlusconi, taking away all opera and most beautiful things in music. They're just cutting these things, stupid people. Look at Netherlands: we don’t need this orchestra, they’re killing off everything that’s fine and good. Now they want the money, where from, from orchestras, let them suffer, how is it possible?

Fortunately there was a huge protest which saved the Dutch Music Centre [Muziek Centrum Nederland].

People have to protest all the time now, it’s terrible, because they think, what have we got to lose? This is going to happen anyway.

It’s strange, because concert halls now are fuller than ever. I look at our situation in Britain, we have great conductors in every city, and yet all that could be reduced or taken away – I gather even the RSNO plans for next season have had to be trimmed.

"Oh, please, not this piece or that, you have to change this" - there's always trouble. The price is beauty, which is valued by people, and music is the most important of beautiful things, I think, for people, in life – it enriches people so much. There’s absolutely no more music education for young people.

But I think that also has begun to change, people are more conscious of trying to educate young people again - the situation gets very bad and then it goes up again.

History shows it’s always up and down. American orchestras, you know what is going on? Eliminating public radio stations, eliminating National Endowment for the Arts. There have always been donors, good men. But why support some sexy things in Hollywood? How about great American orchestras? They need help.

American culture is in a worse situation than Britain, isn't it?

But they still have money. But all this thinking comes from narrow-minded people who are running the government.

To return to the relative comfort of the Scots musical scene: when did you last do the Leningrad in the Usher Hall? Was it in the 1980s?

Very possibly, it seems so long ago now.

And here are still many of the same players, right? Like your clarinettist John Cushing.

Naturally, yes, he’s here, a wonderful musician, so good, I’m very happy to see these old faces. They’re looking a little bit different, me too, but still I’m happy… John Harrington, great viola player, is about to retire. I say, "You still play so well, stay with the orchestra." He says, "It’s not allowed." I say, "You’ll have to come to America." In Chicago, when I conducted Glazunov's From the Middle Ages Suite, they had a 91-year-old in the second fiddles. He came to me and said, "I was here when Glazunov conducted this orchestra, I was 17 years old and I’m 91 now." And I was conducting the second performance there after Glazunov. It was 1936 when Glazunov died, you know. Nobody’s taking this player away, it’s very human, but of course he can’t play well –

But he can bring a spirit...

And it’s history, it’s all history.

In German orchestras they’re much younger now, they pension people off very young.

Ya, ya. But the sound is not the same anymore. It’s a multiculture sound in Germany. It’s much better here still. They’re multicultural because there are many nationalities playing there, especially people from Asia, from China, from Japan, and all these girls and boys playing in orchestras. Hear the great New York Philharmonic playing, they’re all Asian girls, half the orchestra, from Juilliard. Look at Karajan, his orchestra, all men playing, it was a sound world, a fantastic sound was in the orchestra. There is a difference. I say nothing bad about women musicians [my friend Ruth, a viola player, is sitting in on the interview; he winks and we all laugh], this is a very dangerous situation, but Karajan actually got kicked for trying to hire a woman.

Sabine Meyer, yes, a truly great clarinettist. The orchestra voted against her and said, ridiculously, that her tone didn't blend.

But which kind of sound it was, the famous Berlin Philharmonic, they changed it now. But it's still very fine.

The principal viola, Amichai Grosz, left the Jerusalem String Quartet to join the orchestra recently.

I know, I know, concertmaster also is a fantastic guy – I did seven concerts with them now, two weeks in a row, wonderful musicians, they’re playing so beautifully.

Watch Järvi conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in the conclusion of Weber's Oberon Overture

I even managed to include in one Berlin programme Taneyev's C-minor Symphony...

Which you also did with the London Philharmonic...

It’s so beautiful, and for them it’s new. Hans Rott's symphony I did with them.

The proto-Mahler symphony... So they're still open to doing unusual repertoire with you?

They want to, and they’re still open, yes, with Simon [Rattle]… and people still come to listen to them whatever they play, but of course they like doing the repertoire which they’re used to playing. The programmes are doing well.

How's the RSNO sounding now, do you think? I reckon that they haven't been on such good form since you were principal conductor - Stéphane Denève has done superb work.

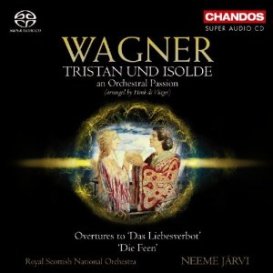

Yes, yes, very beautiful. Time is a little bit limited. We’ve done beautiful Wagner recordings now, and it's completely different Wagner, it's a concert Wagner, with tempi to suit the concert hall. We are not playing in an opera house, the tempi are different, but it’s a wonderful selection from Tristan, from Parsifal, from Ring, and Meistersinger. Yesterday we did two symphonies, do you know how beautiful they are? One is more his style, the other is more like Beethoven and Schubert, you see how much changed when Wagner matured. Fantastic pieces!

Yes, yes, very beautiful. Time is a little bit limited. We’ve done beautiful Wagner recordings now, and it's completely different Wagner, it's a concert Wagner, with tempi to suit the concert hall. We are not playing in an opera house, the tempi are different, but it’s a wonderful selection from Tristan, from Parsifal, from Ring, and Meistersinger. Yesterday we did two symphonies, do you know how beautiful they are? One is more his style, the other is more like Beethoven and Schubert, you see how much changed when Wagner matured. Fantastic pieces!

There’s not much you’ve got left to record, is there?

Halvorsen now [with the Bergen Philharmonic], Norwegian composer; it is sometimes folk music, it is so beautiful. We've done Grieg and a little bit of Svendsen. I like all this unfamiliar music. Atterberg too, and I like to start to record now a little bit of Swiss music [probably with the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, where he has recently taken up the post as artistic and musical director]. Raff, you know Joachim Raff?

Not well, but yes, I'm familiar with some of his music...

You know Raff was in the middle of all these good composers, and wrote all this very good music, but he’s been somewhat forgotten now; you have Mendelssohn, Schubert, Schumann and you had Raff, he was there also; so beautiful, a highly professional musician. And what else…

Have you kept count of how many recordings you’ve done now?

About 450. Plus.

Do you ever go back and listen to them - did you revisit the old SNO Shostakovich Leningrad Symphony recording while you were preparing this?

I like to go back and I listen a lot to other conductors. I change, of course, my tempi and my view is different now to then. I don’t very much like to copy old great performers, I like to do my own view of things – even Bruckner or Mahler or whatever, it always has to be different. Bruckner, I think, was a victim of a lot of people, conductors especially, too slow and slow and it’s just dragging and dragging and it had to be beautiful but it has to go, to flow – music always has to flow.

Watch Järvi rehearsing the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra in Bruckner's Fifth Symphony

So same with Mahler, which finally came out as two-hour symphonies, because it’s beating – ah – ah – ah – ah – music is not in four beats or whatever, always alla breve. That’s why I’m always trying to find new ways – in Shostakovich this time, I started from scratch. I look at the score, and I see how the first version of Bruckner's Third Symphony was, why he wrote three versions, or five of them. Why? You have to discover things in music. And also so many good composers are not discovered, or badly performed. If it’s badly performed, the audience thinks, what? This is a bad composer. No way, it’s not a bad composer.

Like new works which don’t have enough preparation.

But old ones too, we have to look at all these surrounding people who wrote interesting music even at the time of Beethoven and Mozart and Schubert. We always have to keep discovering them.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bach St John Passion, Academy of Ancient Music, Cummings, Barbican review - conscience against conformism

In an age of hate-fuelled pile-ons, Bach's gospel tragedy strikes even deeper

Bach St John Passion, Academy of Ancient Music, Cummings, Barbican review - conscience against conformism

In an age of hate-fuelled pile-ons, Bach's gospel tragedy strikes even deeper

MacMillan St John Passion, Boylan, National Symphony Orchestra & Chorus, Hill, NCH Dublin review - flares around a fine Christ

Young Irish baritone pulls focus in blazing performance of a 21st century classic

MacMillan St John Passion, Boylan, National Symphony Orchestra & Chorus, Hill, NCH Dublin review - flares around a fine Christ

Young Irish baritone pulls focus in blazing performance of a 21st century classic

First Person: St John's College choral conductor Christopher Gray on recording 'Lament & Liberation'

A showcase for contemporary choral works appropriate to this time

First Person: St John's College choral conductor Christopher Gray on recording 'Lament & Liberation'

A showcase for contemporary choral works appropriate to this time

Classical CDs: Romance, reforestation and a Rolleiflex

New music for choir, orchestra and string quartet, plus a tribute to a rediscovered photographer

Classical CDs: Romance, reforestation and a Rolleiflex

New music for choir, orchestra and string quartet, plus a tribute to a rediscovered photographer

Donohoe, RPO, Brabbins, Cadogan Hall review - rarely heard British piano concerto

Welcome chance to hear a Bliss rarity alongside better-known British classics

Donohoe, RPO, Brabbins, Cadogan Hall review - rarely heard British piano concerto

Welcome chance to hear a Bliss rarity alongside better-known British classics

London Choral Sinfonia, Waldron, Smith Square Hall review - contemporary choral classics alongside an ambitious premiere

An impassioned response to the climate crisis was slightly hamstrung by its text

London Choral Sinfonia, Waldron, Smith Square Hall review - contemporary choral classics alongside an ambitious premiere

An impassioned response to the climate crisis was slightly hamstrung by its text

Goldberg Variations, Ólafsson, Wigmore Hall review - Bach in the shadow of Beethoven

Late changes, and new dramas, from the Icelandic superstar

Goldberg Variations, Ólafsson, Wigmore Hall review - Bach in the shadow of Beethoven

Late changes, and new dramas, from the Icelandic superstar

Mahler's Ninth, BBC Philharmonic, Gamzou, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - vision and intensity

A composer-conductor interprets the last completed symphony in breathtaking style

Mahler's Ninth, BBC Philharmonic, Gamzou, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - vision and intensity

A composer-conductor interprets the last completed symphony in breathtaking style

St Matthew Passion, Dunedin Consort, Butt, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - life, meaning and depth

Annual Scottish airing is crowned by grounded conducting and Ashley Riches’ Christ

St Matthew Passion, Dunedin Consort, Butt, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - life, meaning and depth

Annual Scottish airing is crowned by grounded conducting and Ashley Riches’ Christ

St Matthew Passion, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin review - the heights rescaled

Helen Charlston and Nicholas Mulroy join the lineup in the best Bach anywhere

St Matthew Passion, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin review - the heights rescaled

Helen Charlston and Nicholas Mulroy join the lineup in the best Bach anywhere

Kraggerud, Irish Chamber Orchestra, RIAM Dublin review - stomping, dancing, magical Vivaldi plus

Norwegian violinist and composer gives a perfect programme with vivacious accomplices

Kraggerud, Irish Chamber Orchestra, RIAM Dublin review - stomping, dancing, magical Vivaldi plus

Norwegian violinist and composer gives a perfect programme with vivacious accomplices

Small, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - return to Shostakovich’s ambiguous triumphalism

Illumination from a conductor with his own signature

Small, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - return to Shostakovich’s ambiguous triumphalism

Illumination from a conductor with his own signature

Add comment