theartsdesk Q&A: Violinist and Conductor Nikolaj Znaider | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Violinist and Conductor Nikolaj Znaider

theartsdesk Q&A: Violinist and Conductor Nikolaj Znaider

A fine thinker among musicians discusses competitions, Mozart and Nielsen

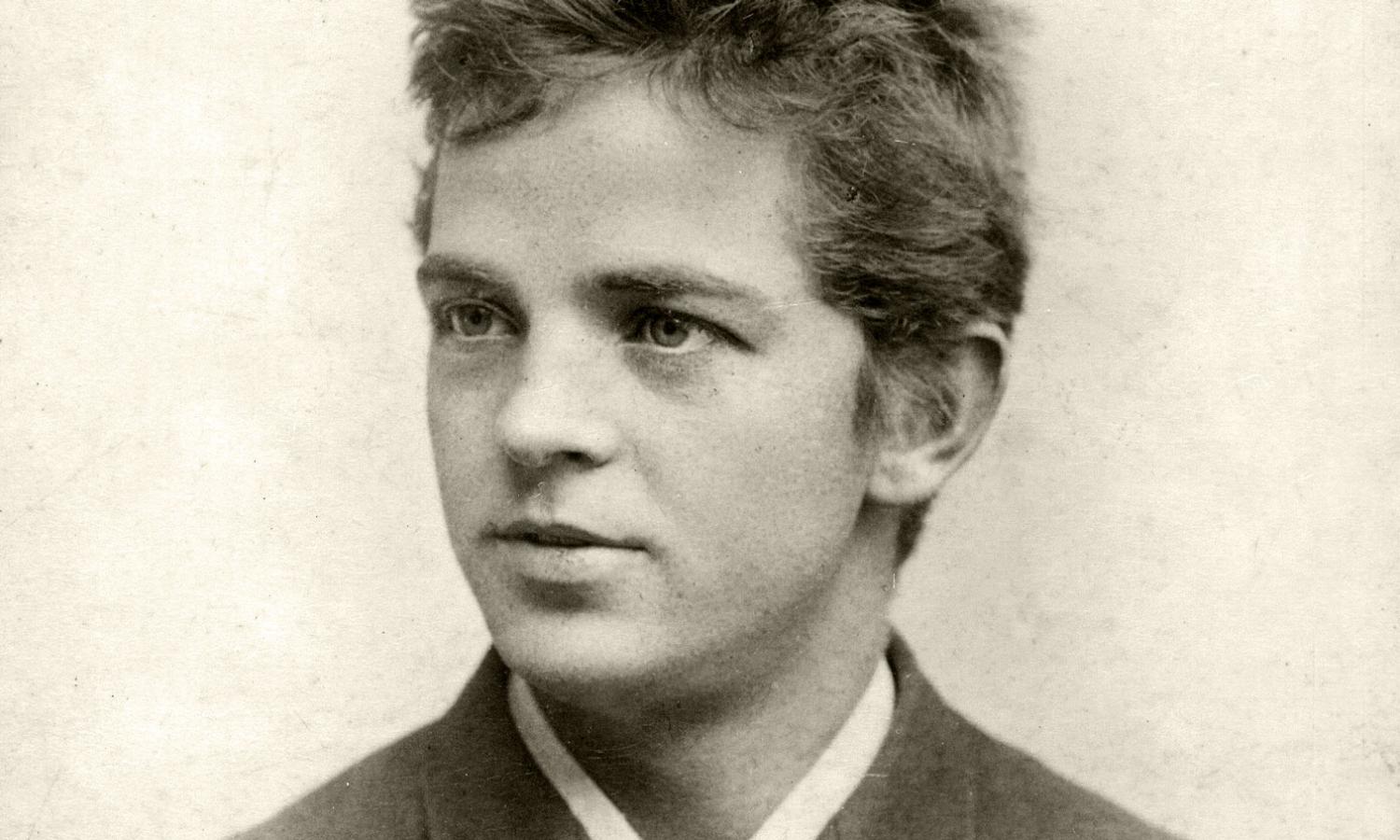

Unquestionably one of the greats as a performer, Danish-Israeli violinist and conductor Nikolaj Znaider divides opinion over his forthright views in interview: either honourable and refreshingly candid, or troublingly indiscreet. After an hour and a half with him between the two finals of the Carl Nielsen International Violin Competition in Odense, I plump fervently for the former.

All this broke on the afternoon and evening of the very last day, after I'd had my interview and Znaider had conducted the very fine Odense Symphony Orchestra for the three finalists' first evening. There was, in fact no signs of "shambles" or disgrace, just a jury majority concerning the chosen three with which Znaider had not agreed, but which he had of course accepted within the rules of the competition. Most of us were delighted with the result: joint first prize to Ji Yoon Li, the most polished artists and the one who for me made most sense of the Nielsen concerto, and Romanian Liya Petrova, who had showed most individuality in the Tchaikovsky Concerto the previous evening (the two pictured below by Knud Erik Joergensen).

Znaider might have been wiser not to say what he did midway through the competition, but he never named his preferred candidate, nor dissed the finalists. And he clearly had integrity in his views about how a competition, if competition there has to be, should be conducted. After complimenting him very sincerely over the best Brahms Violin Concerto I've ever heard live, at the Proms last year with Fabio Luisi and the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra (which Znaider has also conducted), I opened our talk with reference back to his own first involvement with the event.

Znaider might have been wiser not to say what he did midway through the competition, but he never named his preferred candidate, nor dissed the finalists. And he clearly had integrity in his views about how a competition, if competition there has to be, should be conducted. After complimenting him very sincerely over the best Brahms Violin Concerto I've ever heard live, at the Proms last year with Fabio Luisi and the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra (which Znaider has also conducted), I opened our talk with reference back to his own first involvement with the event.

DAVID NICE: You won the competition when you were 16, so I wonder if you can remember much of how you felt at the time, and whether then it was like I've been told it is now – very nurturing and not just the hard lines of the usual competition. What were your impressions?

NIKOLAJ ZNAIDER: In those days it was the usual competition, with a bunch of teachers sitting on the jury. It's always nice when you win, even if coincidentally it's the thing you learn the least from. But when you're very young you don't learn much about yourself from it, and what I was trying to tell the contestants who didn't make it to the next round is that first of all there is this extraordinary level of coincidence in the decision-making, much more than I had thought. It's my first competition where I am really part of it from beginning to the end, and I've really seen from the inside that you could have reached so many decisions that would have been equally fair.

Now if someone comes and plays everything at the highest level they have a very good chance that everyone will agree. But in the event this is not what happens. Everyone has their own strengths and weaknesses, and we have I think been following too closely the traditional pattern of repertoire choice with Bach, Paganini and the first Brahms, and there are some people who just don't have the technique necessary for a great Paganini caprice.

On the other hand that doesn't mean you can't have a career in music, it doesn't even mean you can't become a violin soloist. So how do you gauge that and weight that with someone who does give a great Paganini caprice but falls maybe during the Mozart sonatas, especially when you're choosing between unknowns, it's like you only see a little bit of the arm and not the whole person – you have to see more. So we don't have enough factors, and you try to make educated guesses, but in the end what was important to me was to have a jury first of all free from teachers.

Now why do I say that? It's not as if I'm trying to say every teacher is a cheat, but even we know there are teachers who have cliques who vote for each other – this is well known. Even if you have teachers who don't have students or are not allowed to vote for their own students, they can vote for other students. When your livelihood depends on the level of student you get, who apply to study with you, we know how the human mind works, it's not objective, it's easily influenced. With a few words of review you're a pocket psychologist. I don't pretend to be an expert but I read a lot, it's so influential – you say a little word before a person hears something and it alters completely the way you listen to them.

So therefore I don't trust the human mind, and I wanted to take that element out of the equation. It means that no one on the jury teaches, no one has anything to gain from Contestant A or Contestant B winning. Now, does that mean we all agree? No. But at least there's one less danger. So that was important to eliminate, but still you end up with people weighing different things, and what I would say which was important to communicate to everybody is that there can be someone at home who righteously watches the competition as it progresses online and says, I can play like that, so I say, yes, that is something that's not communicated at competitions, you're presented with a jury that seems to be all in agreement, and what you're presented with is by default a very black and white scenario. You, not you, yes, no.

So therefore I don't trust the human mind, and I wanted to take that element out of the equation. It means that no one on the jury teaches, no one has anything to gain from Contestant A or Contestant B winning. Now, does that mean we all agree? No. But at least there's one less danger. So that was important to eliminate, but still you end up with people weighing different things, and what I would say which was important to communicate to everybody is that there can be someone at home who righteously watches the competition as it progresses online and says, I can play like that, so I say, yes, that is something that's not communicated at competitions, you're presented with a jury that seems to be all in agreement, and what you're presented with is by default a very black and white scenario. You, not you, yes, no.

The truth of the matter is that it's much more nuanced than that, and with hindsight, knowing what we now know, the other people would have been equally deserving or might have done better going on in the competition. And I think it's important to know first of all, because as an encouragement factor but also to recognise those performances that were very good, and that by luck, maybe someone played over lunch or the jury was a little bit tired. Or you came after someone who played fantastically, or after someone who didn't do so well. Anything – the kind of pianist you got, so the result doesn't even reflect what the jury thinks. I'm not a dogmatist, on the contrary I'm an idealogical un-dogmatist, I believe strongly that there's not nearly as clear-cut an answer to many things in life as we want. I am the same when I conduct. Often I get questions from musicians that are reductionist in nature, that try to boil things down to yes, no, loud or soft or when does the crescendo start. Well, it depends what happens before it, it depends how we're going to continue the phrase there.

You're the one in charge when it comes to the whole picture.

It's not a cop-out to be more nuanced in response. That actually requires more discipline and it's more difficult to maintain a logical line of thought through something which is more flexible.

Do the entrants get feedback at every point?

The ones who don't make it, yes, they have a chance to speak to the jury – no one's forcing anyone. I don't think that's a novel condition, but I think the humanity with which they are met might be novel. We're not standing here and telling them about technical points – or only a bit – because we're not teachers, we have a different reaction. I think all of us care about the competitors and want to help them. I'm meeting with some of them after the competition, they're coming to play for me when I'm in another city and so forth, so that's what this competition does – it's a platform if you win, of course, but it's also a platform to meet people on the jury and to receive advice and to learn.

It's good for them to talk to each other, too.

Yes, it's all good. It's a very lonely life to be a musician.

The other question is whether they would all be solo musicians, because there's so much satisfaction to had in chamber music, some would say more than in a life travelling playing the big virtuoso concertos. What criteria do you ultimately have for choosing the winner – is that the same?

The other question is whether they would all be solo musicians, because there's so much satisfaction to had in chamber music, some would say more than in a life travelling playing the big virtuoso concertos. What criteria do you ultimately have for choosing the winner – is that the same?

For me the very simple question is, who would I pay money to go and hear? In the end, there must be that. (Pictured above: Znaider with runner-up Luke Hsu). On the other hand there are many factors that you have to take into account to try and be fair to everybody. My opinion is if someone's an incredibly accomplished, mature performance, you have to acknowledge that. But to what degree?

Because some are quite established already.

Yes, many of them have done a lot. So in the end it's very subjective – there has to be this element of sympathy and what speaks to you.

Do you also take into account how much one player could develop? That one might be accomplished, but another might go further and benefit from winning the competition?

Sure. There the more you know about violin playing, if we're talking about ability, the more you are familiar with that the more you can gauge if they have systemic problems, how old are they. If it's a musical case, it depends slightly on age – the younger the more malleable, obviously, but you have to see something. I feel you can see whether one person has the potential to develop further – but again, we are not prophets, we don't know. I always thought that when I was younger – to be a good student is not easy.

First of all you need to identify who the right teacher is – you have to identify what your weaknesses are, and you can't leave that in the hands of someone else. You need to take a very hard, honest look at yourself and say, what do I need? It's easy enough to identify strengths. Then you have to be lucky enough to find that teacher, to get in that class, to have the funds, whatever. Then when you get to that point you have to think in many ways, it’s not just a one-track mind, you have to absorb everything from that teacher. (Pictured below, Znaider with inspirational teacher Boris Kuschnir)

It doesn’t even mean you agree with everything he or she does, long-term, but you have to be in it completely. It’s not easy, the violin is a terribly difficult instrument, technically anyway, just to get a decent sound. And to get a decent sound you are old already, and you have to have been taught music properly – if you don’t know what a Neapolitan subdominant is and why that is important to know, then by the time you’re 22 your brain isn’t structured to think about music in the right way, and you end up with all the divas, the ones who can make a nice melodic line, but who have no idea about listening to others or adjusting to an ensemble.

It doesn’t even mean you agree with everything he or she does, long-term, but you have to be in it completely. It’s not easy, the violin is a terribly difficult instrument, technically anyway, just to get a decent sound. And to get a decent sound you are old already, and you have to have been taught music properly – if you don’t know what a Neapolitan subdominant is and why that is important to know, then by the time you’re 22 your brain isn’t structured to think about music in the right way, and you end up with all the divas, the ones who can make a nice melodic line, but who have no idea about listening to others or adjusting to an ensemble.

That’s another thing, catching a soloist who really works with the conductor and the players, it’s quite rare.

That’s why it was very interesting yesterday to conduct [the Brahms and Tchaikovsky violin concertos from the three finalists], because you feel very strongly the give and take. When I play with conductors, I feel I know exactly when there’s a kind of wordless communication, where the music becomes alive. Because I don’t know about the audience, but I like to hear musicians speaking, reacting, talking to each other, proposing something which is then an idea which develops.

I’m allergic to the autopilot phenomenon, it drives me mad, especially when I conduct, because I’m dependent on what comes back. When I play at least I’m somebody in charge, and in the worst case scenario I can build a mental wall around what happens around me. As a conductor you’re completely dependent on the orchestra, which is doing just what it did in the previous concert – you try to wake them up and get your attention, it’s like playing tennis against the wall, but the wall is a hedge and nothing comes back. That’s the worst thing for me. We need to develop violinists who think musically from the beginning. How do you measure that, someone who plays the instrument fantastically well but isn’t aware musically? It’s difficult.

There are a few conductors, very few it seems to me, who are ideal partners, who really listen to the soloist. Andrew Davis is remarkably good at that: I’ve seen him working with violinists and pianists where the give and take is remarkable. But I can still count performances like that on the fingers of two hands. And you usually get little time to rehearse.

Yes, usually, but that shouldn’t be necessary. Everyone’s accomplished enough. It just speaks right away. Luisi did a marvellous job with the Brahms – did the orchestra sound good?

Really good, yes.

I'm happy that he’s there [with the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra]. I came and did a Bruckner Nine with them the next month which was very good, I was very surprised. They did very well.

For you, developing from 16, was it there for you from the start, after the competition? Did it take a long time to learn lessons like that, collaboration, or was it instinctual?

I had a great piece of luck, which was that when I was 12 Isaac Stern came to Denmark, and it was arranged that I should play for him. And he said, he’s a very talented boy but he doesn’t know what he’s doing. He told my parents, you need to get him music harmony, theory, history, you need to find someone to teach him. And that was a very good recommendation. My parents got together some funds to pay for private tuition, and since a very early age I studied with the best theory and formal analysis professor from the academy in Denmark, Axel Matthiesen.

He taught me like he taught his composers – he was quite brutal. He was famous for telling people, maybe you should find another job, you’d be good in advertising. Sometimes he told me to come and sit in his organ class, where they do advanced theory and harmony, I was 12, 13, 14. We started doing analysis of Mozart sonatas, of trio sonatas from the Baroque period, I remember analysis of the Brahms Alto Rhapsody, so it kind of structured my brain to think about music in those terms.

Now when I won the competition, to return to your question, nothing initially happened much in the sense that I didn’t get the reach to have a platform to launch a career, which is what we’re aiming to build here. So I continued my studies and I became violin-obsessed, and right at that time my arms had just grown about 20 centimetres, so I needed to figure out again how to play the violin. Then I went to New York for a year, then I came to Vienna and studied with Boris Kuschnir, who I think is the greatest violin magician, and for some years I was deeply involved with that, it never left me, the brain was structured to think about music in those terms. So then, after having competed in the Queen Elizabeth Competition in 1997, when I started to work in more mature fashion with conductors like Barenboim, whom I studied with in fact, then thinking about music in those terms was simply a continuation of what I had been taught.

It was a very organic process.

For me it was. But I know a lot of people who have studied formal analysis because people tell them they should, but they have no idea what that means when they play a sonata or a concerto. It’s not applied in any way. Then you begin to have a generation of uninformed violinists. We need to see if we can stimulate a different discourse so that the young students are aware how decisive that side of the development is.

And what about wider experience of life?

I remember people saying to me when I was 14, oh you have to go and have your heart broken, and you have to experience this and that, and you think foolishly, how’s that going to help anyone? And all these platitudes which are easily said and hard to do anything about – you can’t force it, you just have to live life and embrace it.

In terms of reading and cinema…

The more layers you have the better. Especially with conductors, but also with instrumentalists – the ones we really admire are the ones who keep developing. You only keep developing if you add layers to what you have, and those layers become more – well, they start out being very myopic, you start with the subject matter itself, then expand and expand.

Did you feel there was any point in your life that specifically changed your attitude to playing, or has it been a constant development?

I think it is, when you look back it’s been a constant development. I am just the type to always search for different answers, different insights. There were certain things that have contributed greatly to it, certain people, discussions with certain conductors, Barenboim, Colin Davis, and others who were very generous with their time and where your mind starts to work in a different way. Just starting to conduct myself two years ago by itself opened my mind incredibly.

That must be very strange, conducting concertos you know well as a player.

That must be very strange, conducting concertos you know well as a player.

It’s easy. I know it so well I could do anything to help, and it’s my mission with these players, for example if they were about to do something that didn’t make sense, to nudge them gently in a different direction but not to interfere too much, it was very interesting to see how much they responded to impulses that came the other way. Well, actually only one did that to me, from where I stood – it may have felt differently to the audience.

One thing that really changed and added another layer not only of comfort, perhaps of ability, I’m not sure if that is the right word, was when I started to conduct opera, when I got into that world.

Which operas have you conducted?

The three Mozart-da Ponte operas, some Verdi, and now I’m studying Wagner. I did Lohengrin for the first time, some Strauss will come eventually.

But there can’t be a better education than the Mozart-da Ponte operas.

They’re the best, the best that has been written by anybody ever. I think Bach, if you play music or listen and say, this is the greatest music whenever you’re playing it – like Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is the greatest ever, then the Grosse Fuge or Op 111. But then you take Mozart and you say, no, that is the greatest. And you can do that with a lot of composers – Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler, Schoenberg in his way, Stravinsky. I’m not by nature a big Stravinsky fan, but Sacre was like an earthquake, it shakes you to the core. Schumann, Mendelssohn. But there’s just something about Mozart whenever I return to it, I don’t know if it’s just the pure genius, the simplicity of it, as if he could express all the suffering, agony, aspirations, nobility, vulgarity – everything of the human condition in the most simple of phrases, with no time or effort spent on it, at least just listening to it, it expresses everything.

To get that flow, though, as a conductor – I’ve seen one Figaro where the first two acts just ran as if they’d lasted 10 minutes.

Well, Figaro is the right piece for that, Cosi up to a point, but Giovanni is much more difficult to stage – the music is great but the drama doesn’t roll along quite so easily. Also the problem with Don Giovanni is that it starts with the high point, the climax, and then nothing much happens for a long time, you get different episodes, you have the ball at the end of the first act, but then after the final graveyard scene, then it starts to accumulate again and become this incredible thing. In Figaro, this flow of events, every number just flows into the next just the way it happens, you almost can’t mess it up – it seems so logical. But that’s the wonderful thing about opera – it’s music where your dramatic sense needs to be at its highest.

How does that affect your violin playing, then?

I can’t play Mozart the same any more – it’s more dramatic, as in understanding – and this is what we talked about, more layers. When I hear music I usually have more associations now, ah, this is the gardener coming in now, this is the preparation for a feast, you hear all the music suddenly with a different definition of action. And in Mozart without that, it often doesn’t work. Because the music is contextualised in that way. (Znaider pictured below by Lars Gundersen)

Is it very different from Bach?

Is it very different from Bach?

Very different. Bach is polyphony, it’s a matter of polyphonic hearing. And this is where many violinists struggle. Because we grow up in our practice rooms trying to make a decent sound and play pieces that are so bloody difficult you don’t know where to start or end. And Bach is technically close to unplayable if you want to play it polished and beautifully, just with our modern instruments, with our modern bows especially and our modern strings with the tension that you have, it’s virtually impossible to get it to sound actually nice. But then after that, the sense that you have to hear the voices as separate, even when you’re playing two or three at the same time, you have to be able to play them so that in the hall, from a distance, they sound like absolutely separate voices.

[Nathan] Milstein had a fantastic sense of polyphony, of the composer’s mind, he made wonderful arrangements and transcriptions. Heifetz was another. Now, it’s not my style of playing, it sounds like Heifetz, not Bach, that’s aesthetics, and it’s too quick and too this and too that, too romantic, but the sense of polyphony and structure – Heifetz was also a great pianist. So again we’re talking layers, if you can play piano, if you can compose, the more you can do as a musician the more deep you have a chance to become.

Can I ask you one last question about Nielsen? Because that concerto is such a special case…

Not so special, I don’t think…

OK – but it’s going to be very interesting to hear all three finalists playing it tonight when one of them last night, it seemed to me, had a very fixed idea of how the Tchaikovsky should sound; playing Nielsen might create a different case. It’s not as elusive as the flute and clarinet concertos which are very unpredictable, but to me it has the beginnings of that elusiveness – do you understand it differently?

Well, maybe I’m biased because I grew up with it, I played it at a very early age. But I can’t help wonder when I play the piece – because last year was the 150th anniversary.

Yes, I was here, I didn’t catch you conducting the Third Symphony, that was a week earlier, but I was here on the birthday, I heard Saul and David in Copenhagen and then came here and heard the Vienne Philharmonic under Welser-Most in the "Inextinguishable" [Fourth Symphony]

Oh, were you here too? I was here – that didn’t sound like Nielsen at all! It’s a good orchestra but it didn’t sound like Nielsen…

No, it didn’t have any volcanic quality – the slow movement was interesting but that was about it.

You’ll appreciate this – it was a little like orchestras doing Elgar without knowing the idiom, because Elgar can’t just be played as it’s written on the printed page. You have to decipher – his accent means, take time, it’s not a sound thing, it’s a time thing. All those things I learnt from Colin [Davis], the best Elgar conductor. If you don’t know the idiom of Nielsen (pictured below), and you don’t know that there are certain places where you need to speed up, because the music gets repetitive and needs a little bit of help to get through, and then it relaxes, if you don’t know that – and by the way, the concerto too. But what I wanted to say about the concerto is it always strikes me how conventional it is.

It’s relatively early, isn’t it.

It’s relatively early, isn’t it.

Yes, it’s conventional in its structure, barring the prelude, which is very long. But let’s take that away – it’s, what, about three minutes, after that you have an Allegro, like Mendelssohn, Sibelius, Tchaikovsky, it has a standard exposition, development. After the development there’s a cadenza for the violin which goes into the recapitulation and the coda sounds fairly conventional. Then there’s the slow movement, standard fare, and then the rondo, again not really earth-shattering news here, he put in a cadenza – but as a violinist, I find the concerto standard. Who are these theorists who say it’s so unconventional and difficult? Maybe someone gave it a label 100 years ago?

Maybe I didn’t understand that there is an introduction.

Well, even Nielsen – maybe this sounds a little arrogant, but I don’t mean it to be – described the first movement as being in two parts. But it’s not two parts, there are three movements with an extended introduction. It’s like Mendelssohn who, because of Wagner, got this label of being slightly superficial – nothing could be further from the truth. This thing stuck somehow, and it’s almost like a stigma – not out of malice, again we return to the susceptibility of the mind, someone tells you this is a strange piece and you go, oh, yes, it’s strange. I don’t have a problem with access to it, but I realise that a lot of people do, they don’t know what to do with it.

What can be tricky is the last movement. If you play the first movement too romantically, you can still pull it off in a grand style, even the second movement is kind of Wagnerian. The rondo needs an understanding of the character. When I was younger and more immature, I remember thinking that the third movement was the concerto’s weakness, it doesn’t have a really strong ending, there isn’t so much to hold onto. Now I think it’s the greatest part of the concerto, this underplayed humour, like the last movement of the "Espansiva" [Third Symphony].

And there’s the quirkiness of the "Four Temperaments" [Second Symphony].

Yes [sings a phrase], very Nielsen. But even if the music seems similar to what we know, the character is slightly different. When I first saw the music of the "Espansiva", I thought of the finale, ah, Brahms First Symphony [sings the great melody], this kind of broad grandeur, it looks like that, but it has much less ambition, what did Nielsen say – it’s like somebody walking down the road, this naïve, happy, content mood. If you miss that, it falls flat.

I love it that the transformation of the finale theme in the "Four Temperaments" is like the cheeky trio tune of the second Elgar Pomp and Circumstance March.

But you know what fascinates me is that he sounds like he was indebted to a lot of other composers, but it turns out often that he wrote the music before them. He was not attached to the big international scene like Strauss and Elgar, but Nielsen was a law unto himself. And somehow I still hear Prokofiev in the Violin Concerto, elements of Shostakovich, Stravinsky, they were born but not mature.

He’s an interesting composer, he’s getting a bit of a revival – the English like Nielsen, the Scandinavians obviously. Bernstein and now Alan Gilbert conducted Nielsen in New York, so it has somewhat of a tradition, and of course San Francisco with Blomstedt, and Berglund with Bournemouth. The Violin Concerto doesn’t come up nearly so often, and I wonder if it’s because it doesn’t give you that big ending which gets everyone out of their chairs. It’s awkward for the conductor, terribly difficult – but I honestly don’t know why? And why do we always do the same concertos? There's a whole world of interesting choices to make.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Classical CDs: Bells, birdsong and braggadocio

British contemporary music, percussive piano concertos and a talented baritone sings Mozart

Classical CDs: Bells, birdsong and braggadocio

British contemporary music, percussive piano concertos and a talented baritone sings Mozart

Siglo de Oro, Wigmore Hall review - electronic Lamentations and Trojan tragedy

Committed and intense performance of a newly-commissioned oratorio

Siglo de Oro, Wigmore Hall review - electronic Lamentations and Trojan tragedy

Committed and intense performance of a newly-commissioned oratorio

Alfred Brendel 1931-2025 - a personal tribute

A master of feeling and intellect

Alfred Brendel 1931-2025 - a personal tribute

A master of feeling and intellect

Aldeburgh Festival, Weekend 2 review - nine premieres, three young ensembles - and Allan Clayton

A solstice sunrise swim crowned the best of times at this phoenix of a festival

Aldeburgh Festival, Weekend 2 review - nine premieres, three young ensembles - and Allan Clayton

A solstice sunrise swim crowned the best of times at this phoenix of a festival

RNCM International Diploma Artists, BBC Philharmonic, MediaCity, Salford review - spotting stars of tomorrow

Cream of the graduate crop from Manchester's Music College show what they can do

RNCM International Diploma Artists, BBC Philharmonic, MediaCity, Salford review - spotting stars of tomorrow

Cream of the graduate crop from Manchester's Music College show what they can do

Classical CDs: Bells, whistles and bowing techniques

A great pianist's early recordings boxed up, plus classical string quartets, French piano trios and a big American symphony

Classical CDs: Bells, whistles and bowing techniques

A great pianist's early recordings boxed up, plus classical string quartets, French piano trios and a big American symphony

Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Suzuki, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - the perfect temperature for Bach

A dream cantata date for Japanese maestro and local supergroup

Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Suzuki, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - the perfect temperature for Bach

A dream cantata date for Japanese maestro and local supergroup

Aldeburgh Festival, Weekend 1 review - dance to the music of time

From Chekhovian opera to supernatural ballads, past passions return to life by the sea

Aldeburgh Festival, Weekend 1 review - dance to the music of time

From Chekhovian opera to supernatural ballads, past passions return to life by the sea

Dandy, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a destination attained

A powerful experience endorses Storgårds’ continued relationship with the orchestra

Dandy, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a destination attained

A powerful experience endorses Storgårds’ continued relationship with the orchestra

Hespèrion XXI, Savall, QEH review - an evening filled with laughter and light

An exhilarating exploration of innovation in 16th and 17th century repertoire

Hespèrion XXI, Savall, QEH review - an evening filled with laughter and light

An exhilarating exploration of innovation in 16th and 17th century repertoire

Add comment