One of the downsides of the international media’s obsession with the crimes and misdemeanours of Silvio Berlusconi and his make-it-up-as-you-go-along style of government is that anything that doesn’t fit in with the overall narrative of the crazed, corrupt media mogul destroying an otherwise magnificent, well-organised country, tends not to make the headlines.

The UK media is currently full of the Italian premier’s latest assault on the Freedom of Expression. This is a singularly cack-handed bill which aims to prevent one ill - police wire-taps being relayed in the media before trial proceedings are concluded – by imposing something that is potentially worse (a gagging order with stiff fines for editors who ignore the proposed new law). So you are unlikely to have read of another case of Italian censorship which is arguably much worse.

Try this one for size, and importance. A Rome-based music critic of many years' standing named Alfredo Gasponi is poised in the next week or so to have his apartment seized by the bailiffs for non-payment of a €500,000 fine imposed on him by a Rome court for having written an article deemed excessively critical of Italy’s leading symphony ensemble, L’Orchestra dell' Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia.

That’s right: a music critic sued by the members of a well-known orchestra for doing what to most people would be just doing his job: critiquing their standard of musicianship. The article in question was deemed to have “offended (leso) the dignity of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia” – a singular offence which on the basis of lese-majesté one might deem “lese-orchestre”.

But there is more, much more. Gasponi’s article was published in the Rome daily Il Messaggero back in March 1996, and long before the arrival of Antonio Pappano in Via della Conciliazione (the Mussolini-era boulevard leading up to the Vatican where Santa Cecilia have their impressively vast but acoustically unsatisfactory premises). Due to the phenomenal inefficiency of the Italian Justice system (which pre-dates by at least a century the current premier’s frequent run-ins with some of its more politically motivated members), Gasponi has had the sword of Damocles hanging over his head for almost 15 years, as the various stages of the trial procedure are exhausted. His final hopes for overturning the draconian sentence reside in the Court of Cassation in Rome (roughly the equivalent of a Supreme Court, but which can only decide on the correct application of the law itself, and not on the merits of the case), or perhaps the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, if his lawyer Martino Chiocci can gain access there.

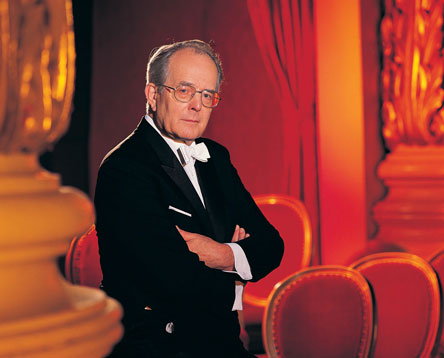

Several other facts render Gasponi’s case even more grotesque. Firstly that he was merely reporting the views of Wolfgang Sawallisch (pictured below right). While praising the overall capacity of Italy’s leading symphony orchestra to execute the chosen programme (Schumann and Hindemith) with consummate ease, the distinguished conductor expressed his frustration with the Italian Musicians' Union-imposed rules which meant that the orchestra’s finest core players were augmented by a series of aggiunti – inexperienced additional players, many of whom were playing in public for the first time.

Secondly, the part of the article that moved the Santa Cecilia players to call in their lawyers was not the text of the interview with Sawallisch as such, but the headlines which some anonymous sub-editor at Il Messaggero had come up with. The main article on the arts pages was succinctly and cleverly titled “Sawallisch: Allegro ma non troppo”, (which hardly needs translation), qualified by a slightly brusquer subtitle: “Il Maestro: l’orchestra di S. Cecilia non è all’altezza del suo ruolo” (they are not up to the job). Meanwhile, the front page teaser went in for the kill, taking a few liberties with the piece itself: “A Santa Cecilia non sanno suonare” – they can't play properly.

Secondly, the part of the article that moved the Santa Cecilia players to call in their lawyers was not the text of the interview with Sawallisch as such, but the headlines which some anonymous sub-editor at Il Messaggero had come up with. The main article on the arts pages was succinctly and cleverly titled “Sawallisch: Allegro ma non troppo”, (which hardly needs translation), qualified by a slightly brusquer subtitle: “Il Maestro: l’orchestra di S. Cecilia non è all’altezza del suo ruolo” (they are not up to the job). Meanwhile, the front page teaser went in for the kill, taking a few liberties with the piece itself: “A Santa Cecilia non sanno suonare” – they can't play properly.

This is a regular trait of Italian newspapers: an unsubstantiated disconnect between the headline and the meat of the article. If you read past the alarmist “Il Papa è grave” , for example – the Pope is seriously ill - the hard news of the story may simply be that the head of the Catholic Church has a persistent cold. So why would the orchestrali at Santa Cecilia take such offence, especially with the well-respected critic and musicologist Professor Gasponi, who personally had nothing to do with the somewhat exaggerated headlines whatsoever? And why didn’t they try suing il Maestro Sawallisch, if they thought he’s been so horrid about them?

And why on earth, 14 years later, under the distinguished new management of the much-lauded Antonio Pappano, don’t the authorities in Via della Conciliazione try to draw a line under this public relations nightmare, and attempt a face-saving out-of-court settlement with Gasponi, who together with his family, is expecting to be booted out onto the street any day now?

Indeed, when the news of the impending pignoramento – judicial seizure – of the critic’s home and its contents resurfaced in April of this year, a series of articles appeared in broad spectrum of the Italian media, supportive of Gasponi and very critical of the court ruling. Without quite reaching the degree of public attention that some of Berlusconi's media and political bugbears have been accorded for their pains, his case has been flagged up as an extreme example of what Italians often call la malagiustizia, our disfunctional justice system. Most recently, and perhaps most effectively, the “Solidarietà ad Alfredo Gasponi” page on Facebook, launched by the critic's sympathisers, which now has 4,100 members (and which theartsdesk readers should feel free to join).

However, the attitude of Italy’s leading symphony orchestra is to say nothing, and let the law take its course. During the annual press conference on 19 May outlining the highlights of the 2010-2011 season and running over the successes of the past season, the Chairman of the Board and veteran musicologist and historian Bruno Cagli chose to make no reference to the case, even when Mauro Mariani of the Italian Associazione dei Critici Musicali stood up to remind all those present of the Kafka-esque situation in which Gasponi finds himself. The attitude of the Board at the Accademia is evidently to say nothing at all about a grotesque event that happened sometime in the last century, trusting that the Orchestra's current sparkling form is answer enough.

Were it not for the widespread public sympathy for his case, Gasponi (pictured left, in a graphic portrait of his predicament) would find himself very much on his own. The original court sentence – confirmed as fair and proper by the Appeal Court in 2008 – also ordered the publishers of Il Messaggero to fork out €2,500 for their part in the case. They did so without too much of a fuss, evidently preferring not to rock the Establishment boat rather than mount an appeal on a point of press freedom.

Were it not for the widespread public sympathy for his case, Gasponi (pictured left, in a graphic portrait of his predicament) would find himself very much on his own. The original court sentence – confirmed as fair and proper by the Appeal Court in 2008 – also ordered the publishers of Il Messaggero to fork out €2,500 for their part in the case. They did so without too much of a fuss, evidently preferring not to rock the Establishment boat rather than mount an appeal on a point of press freedom.

Outrageous technicalities of the original sentence aside, what makes the court’s ruling so interesting is the notion that a music critic can be too critical, to the point of defaming performing artists and their collective brand identity. But what makes this case all too plausible in an Italian setting is the persistent ability of corporatist interests to trump those of the individual - trampling his or her rights of critical expression, in this case - if deemed to represent un disturbo to the collective.

And here lies the deepest nub of the problem at the heart of Gasponi's legal nightmare. The corporatist mentality, which was first introduced into modern Italy in an officially sanctioned structural form under Mussolini, and which has never extirpated in any meaningful sense, is still deeply entrenched in the classical music and opera sectors. What that means is that the unions have the power to hold the theatres and concert halls to ransom, exacting unrealistic demands from their employers, while frequently drawing back from any form of effective quality control.

The respected music critic Dario Della Porta, who is also professor of history and musical aesthetics at the University of L’Aquila, has written and spoken widely on Gasponi’s case. He is scathing about the legal logic employed to muffle potentially unflattering opinions of critics. “If la Roma looses a match because too many minor players are used on the pitch, or Ferrari disappoint in a Formula 1 Grand Prix due to the incompetence of a couple of engineers in the pit, it is evident that the whole team – or the marquee – have to take responsibility for the weakest links in the chain, but that hardly implies that overall the team is no good.”

While Santa Cecilia remains Italy’s symphonic jewel in the crown, and Florence’s Maggio Musicale is still a thriving concern, many of the distinguished symphony orchestras of previous generations have now lost their lustre, or indeed their very existence. State Broadcaster RAI once boasted four world-class orchestras, in Rome, Naples, Milan and Turin. During their golden era, from the early 1930s till the mid-1970s, their recordings and performances were recognised as outstanding.

As a result of mismanagement, declining musical standards (above all with regard to international orchestras which have generally grown in stature), over-exacting union salaries and conditions demands, in 1994 RAI whittled them all down to one, based in Turin. The recording contracts are no longer there, nor are there the eager home and international audiences of former times. But the musical unions seem not to have woken up to smell the espresso.

As a well-informed musical source in Rome who did not wish to be identified for fear of the possible legal consequences of his words tartly put it, referring to the somewhat scanty seasons envisaged by the Italian musical system, especially when certain players manage to arrange their dates for their own convenience: “In an increasingly globalised environment, a country with Italy’s financial problems cannot really justify paying orchestras 14 months' salaries per year for performing for only three months.”

14 months in a year? Yup. La tredicesima and la quattordicesima are two phantom months invented under Fascism and are still much beloved by Italian union negotiators, to big up sometimes meagre salaries via the backdoor. They are about as suited to 21st-century economic conditions in the cultural milieu as Italy’s libel laws are appropriate to its cultural media sector.

Add comment