6000 Miles Away, Sylvie Guillem, Birmingham Hippodrome | reviews, news & interviews

6000 Miles Away, Sylvie Guillem, Birmingham Hippodrome

6000 Miles Away, Sylvie Guillem, Birmingham Hippodrome

The French ballerina is still luminous on a flying visit to the Midlands

When Sylvie Guillem became, at 19, the youngest person ever to reach the top rank of the Paris Opéra, she gained a job title – étoile (star) – that uncannily captured her essence. Most companies call their top dancers principal or prima ballerina or soloist, titles that show they have first place among their peers. Sylvie too stands out among her peers, blessed as she is with an extraordinary body, an extraordinary work ethic, an extraordinary intelligence.

That’s not to say that she’s perfect, nor that everything she does is perfect; she’s a human being. But the pieces she chooses to dance are always worth engaging with, because they have proceeded from that fire, been scrutinised by that intelligence, forged by that work ethic, and not least because they are animated by that body, which at 49 is still astonishing. This week, the International Dance Festival in Birmingham played host to two performances of her 2011 solo (ish) show, 6000 Miles Away, a triple bill of serious pieces by contemporary choreographers Jiří Kylián, William Forsythe and Mats Ek.

Kylián’s 27’52” is a decidedly mixed affair. With almost no set (the lino on the floor gets to move, slightly), almost no costumes (two pairs of trousers and, sometimes, one top) and a discomfiting soundtrack of slow-bowing high strings, opaque sentences in French and German, and metallic percussion (like someone beating a garage door with a crowbar), it offers little that’s immediately enticing or likeable. The relationship it shows us between dancers Aurélie Cayla and Lukas Timulak is at worst an unhappy, oppressive one, and clichéd at that (Cayla runs desperately back and forth: she must feel trapped!) Timulak’s dancing lacks spark, and a very unfortunate facial resemblance to Vladimir Putin makes the hard-faced and often rough character he plays even more unsympathetic.

And yet, and yet: there is interest here. Cayla has to dance topless for a while; the visual parity this sets up between her and the bare-chested Timulak blurs the conventional gender-binaries of duets like this. Cayla often falls (cliché alert! weakness!) but always with self-possession; her character has more grit than we think, and she moves gorgeously, with a control and airy fluency that makes it look like she’s hanging in the air, in slow motion.

Forsythe’s Rearray, the next piece, is more of the same: an intense, stony-faced duet against a black backcloth between dancers in clothes so ordinary they barely count as costumes. This time it’s Guillem and Massimo Murru who have a relationship to work out, expressed through Forsythe’s incredibly cerebral dissection of classical ballet tradition. The problem is that tradition is so rarefied that only a handful of people in the world are equipped to fully appreciate its intelligent deconstruction. Rearray filled me with admiration for Forsythe’s intellect, and Guillem’s (who commissioned the piece for herself, originally with Nicholas Le Riche as partner, pictured below left), and for the intense connection between the two dancers performing such demanding material, but I was also exhausted. For mental effort, watching Rearray is up there for me with trying to read philosophy in another language: you have to be completely focused all the time. With the harsh lighting, bare stage, and David Morrow’s unforgiving minimalist score offering neither hermeneutic help nor aural pleasure, it’s a long 20 minutes: rewarding in the end, but you have to work for it.

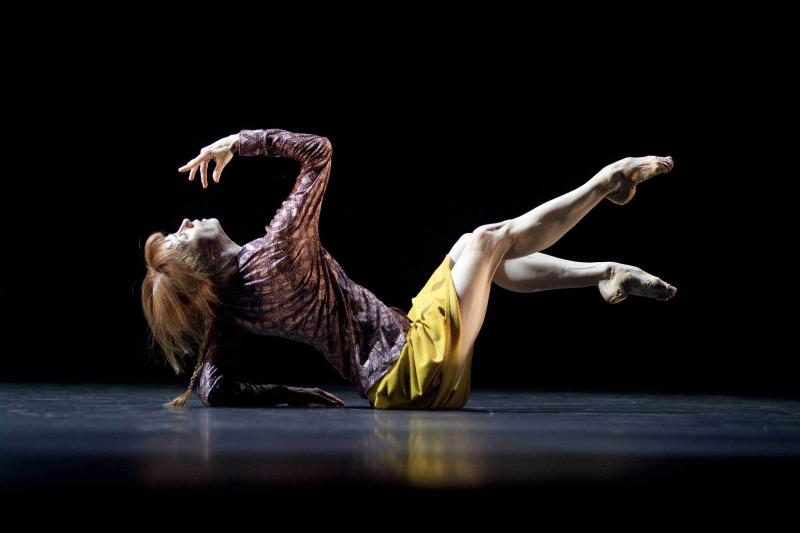

How wonderful then to end with Mats Ek’s Bye, a solo for Guillem that's in a much less elevated choreographic language, and puts all her richness of character and inner light on view. The curtain rises on a video projection of Guillem’s eye in close-up, and the intimacy so established never dissipates: though her character is, when dancing, mostly intent on her own thoughts and memories, Guillem’s face has drawn us in with the honesty of her inner life. Her baggy socks and cardigan suggest both an older woman and a schoolgirl, and Guillem is one and both at the same time, dancing us through the stages and characters, the riches and rebellions of a life that seems at once rather ordinary, and transcendently beautiful. Carried along by the sweeping, story-telling emotion of Beethoven’s last piano sonata, No 111, the audience follows her breathlessly on this elegiac, spirited journey of reminiscence, and when it ends, applauds her with thunderous rapture, calling her back for bow after bow, just to keep her magic on the stage a little longer.

How wonderful then to end with Mats Ek’s Bye, a solo for Guillem that's in a much less elevated choreographic language, and puts all her richness of character and inner light on view. The curtain rises on a video projection of Guillem’s eye in close-up, and the intimacy so established never dissipates: though her character is, when dancing, mostly intent on her own thoughts and memories, Guillem’s face has drawn us in with the honesty of her inner life. Her baggy socks and cardigan suggest both an older woman and a schoolgirl, and Guillem is one and both at the same time, dancing us through the stages and characters, the riches and rebellions of a life that seems at once rather ordinary, and transcendently beautiful. Carried along by the sweeping, story-telling emotion of Beethoven’s last piano sonata, No 111, the audience follows her breathlessly on this elegiac, spirited journey of reminiscence, and when it ends, applauds her with thunderous rapture, calling her back for bow after bow, just to keep her magic on the stage a little longer.

So, not a perfect evening, nor an effortless one. But it’s as I said: Sylvie is une étoile, and she shines. Go bathe in that light if you get the chance.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Onegin, Royal Ballet review - a poignant lesson about the perils of youth

John Cranko was the greatest choreographer British ballet never had. His masterpiece is now 60 years old

Onegin, Royal Ballet review - a poignant lesson about the perils of youth

John Cranko was the greatest choreographer British ballet never had. His masterpiece is now 60 years old

Northern Ballet: Three Short Ballets, Linbury Theatre review - thrilling dancing in a mix of styles

The Leeds-based company act as impressively as they dance

Northern Ballet: Three Short Ballets, Linbury Theatre review - thrilling dancing in a mix of styles

The Leeds-based company act as impressively as they dance

Best of 2024: Dance

It was a year for visiting past glories, but not for new ones

Best of 2024: Dance

It was a year for visiting past glories, but not for new ones

Nutcracker, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - Tchaikovsky and his sweet tooth rule supreme

New production's music, sweets, and hordes of exuberant children make this a hot ticket

Nutcracker, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - Tchaikovsky and his sweet tooth rule supreme

New production's music, sweets, and hordes of exuberant children make this a hot ticket

Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake, New Adventures, Sadler's Wells review - 30 years on, as bold and brilliant as ever

A masterly reinvention has become a classic itself

Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake, New Adventures, Sadler's Wells review - 30 years on, as bold and brilliant as ever

A masterly reinvention has become a classic itself

Ballet Shoes, Olivier Theatre review - reimagined classic with a lively contemporary feel

The basics of Streatfield's original aren't lost in this bold, inventive production

Ballet Shoes, Olivier Theatre review - reimagined classic with a lively contemporary feel

The basics of Streatfield's original aren't lost in this bold, inventive production

Cinderella, Royal Ballet review - inspiring dancing, but not quite casting the desired spell

A fairytale in need of a dramaturgical transformation

Cinderella, Royal Ballet review - inspiring dancing, but not quite casting the desired spell

A fairytale in need of a dramaturgical transformation

First Person: singer-songwriter Sam Amidon on working in Dingle with Teaċ Daṁsa on 'Nobodaddy'

Michael Keegan-Dolan’s mind-boggling total work of art arrives at Sadlers Wells this week

First Person: singer-songwriter Sam Amidon on working in Dingle with Teaċ Daṁsa on 'Nobodaddy'

Michael Keegan-Dolan’s mind-boggling total work of art arrives at Sadlers Wells this week

Add comment