Behind the Scene at the Museum: The Staging of the Diaghilev Exhibition | reviews, news & interviews

Behind the Scene at the Museum: The Staging of the Diaghilev Exhibition

Behind the Scene at the Museum: The Staging of the Diaghilev Exhibition

Tentacles across all the arts - the inside story and detailed guide

The show's curator Jane Pritchard revealed this wonderful kitchen story in a unique walk-round with theartsdesk this week. Her two-year hunt ranged from Diaghilev's passport to glorious Nijinsky costumes, from the Ballets Russes accounts book to astonishing Picasso stage cloths, from precious notated scores by Stravinsky to automated Constructivist art, from ballerinas' slippers and early colour film to Yves St Laurent fashions.

ISMENE BROWN: Jane Pritchard, you have been working on this for well over two years now - it's not so much where you start as where you draw the line, isn't it? How many objects have you settled on?

JANE PRITCHARD: There are essentially 300 exhibits, though some of them have parts. On top of that we have AVs and film which I regard as just as important. I felt very strongly that this is an exhibition about live theatre, rather than just an "exhibition". Around 200 of the 300 are from V&A, which is full of wonderful Ballets Russes treasures already, and 100 are loans, about two-thirds of them from public collections, and a small number in private collections.

JANE PRITCHARD: There are essentially 300 exhibits, though some of them have parts. On top of that we have AVs and film which I regard as just as important. I felt very strongly that this is an exhibition about live theatre, rather than just an "exhibition". Around 200 of the 300 are from V&A, which is full of wonderful Ballets Russes treasures already, and 100 are loans, about two-thirds of them from public collections, and a small number in private collections.

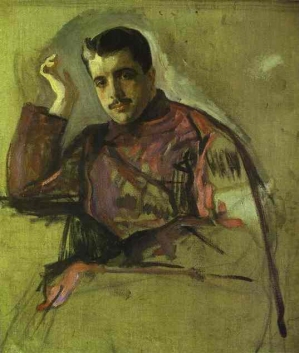

There are a few things that got away from private collections. One or two things. The two things I’m most upset about not getting are the Serov portrait of Diaghilev (pictured right, © Russian Museum, St Petersburg) and the original Picasso of the two women on the beach [the original design for his Train Bleu frontcloth], which is in the Picasso Museum. We were originally promised it but it’s one of the most requested paintings, and it got sent somewhere else. There's a lot of politics goes on about which exhibition gets the best value for your picture.

There are many huge European art names associated with Diaghilev: Picasso, Matisse, Chanel, Rouault, De Chirico, Braque... Was it easy to get the big names for this? They’re the ones who’ll draw the public, but are they always the most significant?

I think we’ve got an incredible balance of big names scattered through and everything else. In terms of Picasso we have two designs for his Chinese Conjuror costume and the actual costume itself, the Train Bleu cloth, and we also have his portrait of Léonide Massine. Of Matisse we have four costumes from Le Chant du Rossignol, which I think are glorious. We have a good representation of Léon Bakst costumes, and actually have a lot more in the museum's stores, though some were too fragile to put on show.

But it’s actually like the costumes were auditioning for the show. You could only have a very few costumes that required a great deal of work. (Pictured left, the V&A's Susana Hunter working on a Matisse Rossignol costume.) Some had already had a great deal of conservation on them - they tended to be star items that people have often wanted to see. But in costumes at the V&A we are much stronger on the early years than the later years, the 1920s, which was the challenge to find elsewhere.

But it’s actually like the costumes were auditioning for the show. You could only have a very few costumes that required a great deal of work. (Pictured left, the V&A's Susana Hunter working on a Matisse Rossignol costume.) Some had already had a great deal of conservation on them - they tended to be star items that people have often wanted to see. But in costumes at the V&A we are much stronger on the early years than the later years, the 1920s, which was the challenge to find elsewhere.

At what point did Ballets Russes costumes start being collected? Mostly dance is seen as such an ephemeral artform that when it’s out of fashion no one cares if it’s lost, or even if a theatre burns them to make room for more.

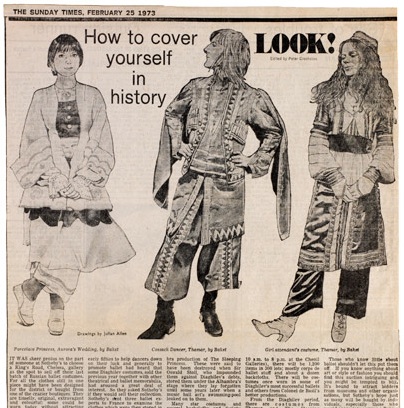

I think it’s a quirk of fate that so many survived. There wasn’t a tradition of collecting them either at the time or even later. There was an auction in 1967 that included a few costumes and it was one of the first celebrity sales around the Ballets Russes. By the last big auctions it was the hippy era, and the market they thought there was was for people buying those costume to wear at parties or to hire out. There are costumes in this exhibition that people really did advertise: “Get this hippy outfit here”. Quite extraordinary. (Picture below, Sunday Times 1973 article showing models in Ballets Russes costumes.)

The first sale had a small selection of costumes largely kept by Sergei Grigoriev, the Ballets Russes balletmaster, and around that auction there was a series of soirees, with people like Princess Margaret there, to raise money for the Royal Academy of Dance. But it’s also quite clear that Sotheby’s was out wooing people to see what they had. So by the next sales round in 1968 there were quite a few more people who’d been involved in the company had come forward wondering if this was the time to sell. So some of the things were, to current eyes, sold very cheap. Some stunning things: such as Marie Rambert’s annotated score of Rite of Spring. It’s now I believe in Switzerland in the Stravinsky Foundation. Not inaccessible, but not readily accessible.

The first sale had a small selection of costumes largely kept by Sergei Grigoriev, the Ballets Russes balletmaster, and around that auction there was a series of soirees, with people like Princess Margaret there, to raise money for the Royal Academy of Dance. But it’s also quite clear that Sotheby’s was out wooing people to see what they had. So by the next sales round in 1968 there were quite a few more people who’d been involved in the company had come forward wondering if this was the time to sell. So some of the things were, to current eyes, sold very cheap. Some stunning things: such as Marie Rambert’s annotated score of Rite of Spring. It’s now I believe in Switzerland in the Stravinsky Foundation. Not inaccessible, but not readily accessible.

If you were picking out the half-dozen most precious things - now that you’ve got so close to all these things - what would be your desert island choice.

One’s got to include at least one costume, so I would go for the Festin costume worn by Nijinsky, which we have in the exhibition. And having a cloth is essential, a huge object - and I am more excited by seeing Natalia Goncharova's Firebird stage cloth actually even than the Picasso Train Bleu. I also have a very high opinion of Goncharova's art generally.

I would also say the bit of film that we’ve only discovered very recently, Tamara Karsavina dancing a "Torch Song" created for her by Fokine for her to tour with. I had my ear to the ground and heard it had been found, and the key figure in making it accessible is David Robinson, a film historian who has done a great deal to make available film material for this current Ballets Russes celebration.

And also because I think movement and understanding how it's made is important I would say the Nijinsky annotation of his choreographic score of L’Après-midi d’un faune is also something of huge importance, and I’m thrilled that the British Library, who own it, agreed to disbind it. Because when they acquired it, they bound it in book form, but you need in fact to read it with two double-page spreads together. And for the last of my five, one cannot think of the Ballets Russes without music, so I’ll pinch one of those Stravinsky scores.

Quite right - art treated in the round, what the eye sees, what the ear hears, what the body feels, what the brain perceives about space, what the senses pick up. How had Grigoriev kept the costumes?

He had kept a handful. Whether he really owned them is moot, as in so many of these cases. He had had it in store, and then Sotheby’s and Richard Buckle went out to Paris, looked at it and got very excited, and decided to do a sale. A three-day sale; paintings and designs, one of ephemera, one of costumes. A year later there was a a similar event at Drury Lane, with dancers modelling the costumes. You couldn’t do that now. Impossible to allow. These costumes are far too fragile. In the 1970s some of them were modelled by Royal Ballet dancers. In the third gallery we have the Prince's costume from Sleeping Princess which was actually modelled by Nureyev.

How long can the costumes last? Do they still have the sweat of Nijinsky, Karsavina, Lifar, Spessivtseva and so on still in them?

How long can the costumes last? Do they still have the sweat of Nijinsky, Karsavina, Lifar, Spessivtseva and so on still in them?

Yes, I suspect so. Sweat gets very ingrained, particularly if you are sweating in a heavy costume, and some of these are very heavy. How long do they last? Well, there are come costumes that are incredibly fragile - if they’re of silk, they could actually shatter. Some costumes you can see have new parts in them, like the Picasso Chinese Conjuror, you see the left arm is clearly a remake (pictured, V&A).

I presume these costumes are a different order for conservation, given that they were working costumes, from say Catherine the Great’s ceremonial dresses in the Kremlin Museum, which are a century and a half older but which I guess got worn only once or twice.

Exactly. These costumes are sweated heavily into, then tossed into hampers to be washed, folded up, crushed, packed. I make no criticism of their wardrobe people, it was just a fact. There is no sense of these being made for posterity - there was no planning in that way. They were made to be shown now, on stage, today, tomorrow. They are very much more vulnerable.

What about exhibits for Coco Chanel and Jean Cocteau?

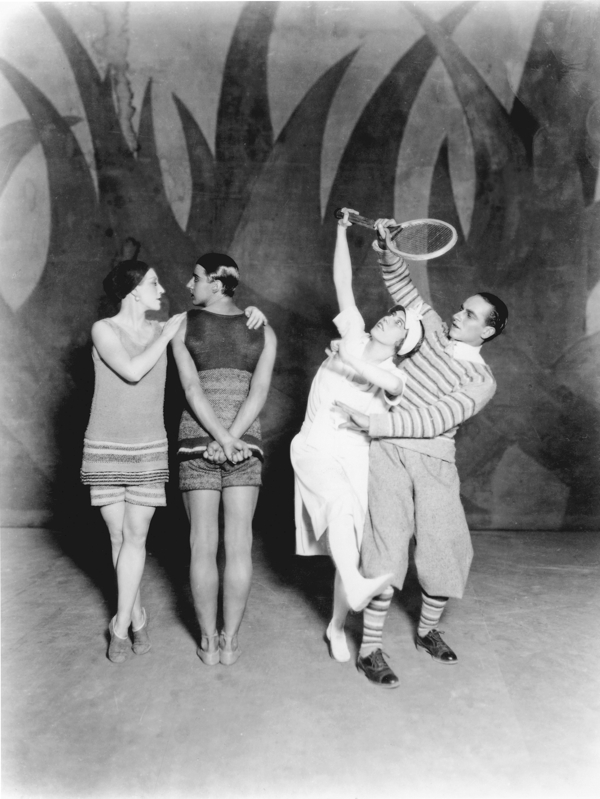

We have Chanel's two bathing costumes from Train Bleu. In fact Chanel contributed rather more to costumes than is sometimes realised, but she hasn’t taken much credit for it. It has been said - and I'd love it if somebody could tell me the truth - that the little flowers on the 1913 Salome costume were made by her before she got much involved in the company. With Cocteau we have a number of drawings, including the wonderful Stravinsky cartoon of him playing Rite of Spring, where visually the music is being transposed onto the paper form, which is glorious. We also have the famous Spectre de la Rose posters for the 1913 season.

That's quite a summary of tasters, but now let’s go round the exhibition.

This first gallery takes us up to 1914, and this starting red area is really Diaghilev’s early years and the company’s background. This rich red was designed by our designer to be theatrical, rather than any connotation with the USSR. It starts with the image that’s based on the reconstruction of the Cocteau drawing of him which was done in 1954 for the Richard Buckle exhibition.

Buckle was an absolutely key figure, wasn't he? I'm assuming that after the Second World War, when the world was in flux and the various Ballets Russes companies were fragmenting and a past phenomenon, this must have been the time when these artefacts were at their most vulnerable.

I think they were, yes. In fact in 1939 there was a significant exhibition of them. But one needs to remember this was summer of 1939, not a good time. It was partly to emulate that that when Buckle was asked to do a show for Edinburgh in 1954 he was determined in a sense to outdo that Serge Lifar one, and get every design and every portrait he could. It was much more works on paper and canvas for him, rather than 3D - as we have here - but Buckle is a key figure in making people aware that what they had were treasures. A number of people starting collecting after seeing the Dickie Buckle exhibition.

He lobbed the ball forward. But of course it actually all starts in the late 19th century, where Diaghilev is running his magazine Mir Iskusstva [World of Art] and generally being a stirrer.

Yes, so here we start with the two volumes of it, the complete run - and we decided to choose the pages that flag up the British connection with Aubrey Beardsley, for instance... Mir iskusstva was showing the new Russian folk art coming through and introducing a lot of European art to Russia.

St Petersburg where Diaghilev was was a very French city, the Tsars' capital, of course, but did he travel a lot to Moscow?

He was aware of the art of Moscow, and aware of what was happening in the Bolshoi and private operas in Moscow. The two great art collecting merchants were also in Moscow. I think the Muscovites at the time were much more adventurous than the St Petersburgers.

Who is this charming little bronze?

Who is this charming little bronze?

It’s a Degas called Preparing for the Dance, so we thought it was appropriate. (Pictured, ballet class photographed 1910 with Stravinsky, Fokine and Karsavina)

[We pass a rich terracotta velvet Queen costume from the Golovine-designed Swan Lake.]

This costume was made for a Bolshoi production of Swan Lake, which Diaghilev bought to put on in London. As we have the greater part of that production in our stores it seemed a good opportunity to use them, and also a neat link with the Chaliapin Boris Godunov, also designed by Golovine, which Diaghilev also brought over to London in 1911.

How do you store such large and cumbersome costumes so that they don’t get crushed? You can’t keep them all on mannequins.

Actually, doing an exhibition gives you the opportunity to rethink your conservation and storage. Increasingly we would try to store things more like this. In the past a lot of things have not been ideally stored. If there’s one thing I’m sorry about it is that I don’t think we brought out enough the opera angle of Diaghilev's enterprise, but because the excuse was the Ballets Russes it was probably inevitable that we focus more on dance.

It's fascinating walking from the very stiff, solid and encrusted opera costumes where singers don’t move about to the costumes for dancers, where the materials must have had to be much altered and developed for their movement.

Even when you look at these dance costumes in the centre revolve - which are largely by Bakst - there is a considerable variation between them. The Daphnis costumes retain their colour very well, because actually that wasn’t a very successful ballet and not done much. Over there is Karsavina’s costume as Zobeide in Shéhérazade which was remade by Bakst. and it surprises people because it’s not what they expect. This is dark blue and beige, not the blue and pink that people automatically think comes from that Ballets Russes production. But Bakst did frequently redesign his dresses for different dancers with popular ballets.

I must say, the light is low, obviously to protect their colours, but I’m missing the strong theatre lights that one expects to see on them. And it’s interesting to see all those pearls around her waist - there can’t be much pas de deux work because the partner would have shredded his hands.

But then in that version of Shéhérazade there wasn’t any great pas de deux as we tend to see in modern productions. That was added on later by Fokine for Vera Fokina.

But then in that version of Shéhérazade there wasn’t any great pas de deux as we tend to see in modern productions. That was added on later by Fokine for Vera Fokina.

So you can tell something about the choreography by reading the costumes... more pearls means less pas de deux!

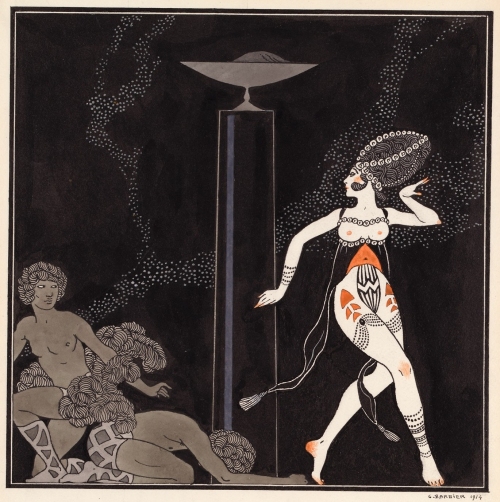

Yes. Now this is the Salome costume for Karsavina that it’s said Chanel made the little flowers for (pictured, George Barbier 1913 illustration of Karsavina's Salome © Harvard Theatre Collection). I think Karsavina hugely enjoyed doing it, but it’s a role that possibly got rather overshadowed, because it was done in the same season as Rite of Spring. And it is a pretty risqué costume for 1913. With the decoration on the bust.

Yes, stars on the nipples. It is extremely sexy and says something about how Karsavina must have been.

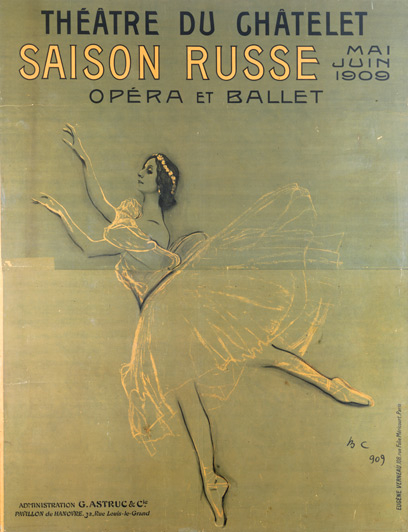

And by complete contrast is this Sylphide costume (pictured below left, V&A), worn by Lydia Lopokova, is as far as we know the only surviving Sylphides costume from Diaghilev’s company. It’s quite an early one, probably around 1916, you can tell from the double wings. I find it fascinating that one thinks one knows what a Sylphide costume looks like - but if you compare this with the 1909 Pavlova poster behind it, by Serov (pictured below right, V&A), which has the blouse affect over the waist rather than the fitted bodice, you see an enormous variation. This dress was Lopokova’s, given to the critic Cyril Beaumont which is how it survived. Because of the double wings we know it’s got to be early. Later ones had single wings with dots on.

Also in the boning of it the paper turned out to be Spanish, so probably not 1910 when she first danced the ballet, but perhaps remade when she returned to the company and they were on tour in America and Spain. The poster is really the only Pavlova item we have on display since she did so little with the Diaghilev company.

Was Alicia Markova a useful source? [Markova was Diaghilev's protegée and baby ballerina from the age of 14.]

We have a lot of Markova material but very little from the Ballets Russes time. She was generous to us and gave us a lot of 3D materials, though her archive materials went over to Boston University, because they have the ability to go out and headhunt celebrity archives in a very active manner, but fortunately before that happened she gave us a lot of costumes and accessories. We do have her boots from Prince Igor in this exhibition.

I imagine that though people fetishise dancers' shoes, they were in most ways two a penny, the most disposable and thrown-away things, compared to costumes.

We do have two ballet shoes from Karsavina and Lopokova, given to Cyril Beaumont probably after one performance, and therefore in pretty good nick.

To drink champagne from! These gorgeous Alexandre Benois designs for Petrushka are very detailed.

These were for show, really, probably from the Thirties. Benois made things more complicated because he would do later drawings but put the original dancers’ names down. One had to learn also that Benois would often do a presentation drawing, such as that one of Sylphides, a valuable souvenir, but not a working drawing.

What a terrific bust that is.

This is the Nijinsky area. First we have two caricatures by Cocteau of Nijinsky and Diaghilev.

They have two of the most recognisable faces, don’t they? Diaghilev’s eyes shoot downwards, Nijinsky’s shoot upwards. It’s feral.

This bust has a wonderful history. When Una Troubridge was modelling it (it's plaster), it had to be when Diaghilev wasn’t around and Nijinsky was off-duty from rehearsals. The bust was then lost, and decades went by. Then Lydia Sokolova found it in 1954 just before the Buckle exhibition transferred from Edinburgh to London. It was in a junk shop being advertised as “a Roman discovery”. Whether this was just a joke I don’t know. But she realised instantly what it was, she had danced in Faune with Nijinsky anyway - she bought it and hurried along to Buckle. It’s an incredibly wonderful thought that these things got lost or hidden away, and then suddenly the right person comes along in the right time and finds it. Someone else could have bought it, or put it in a Roman exhibition!

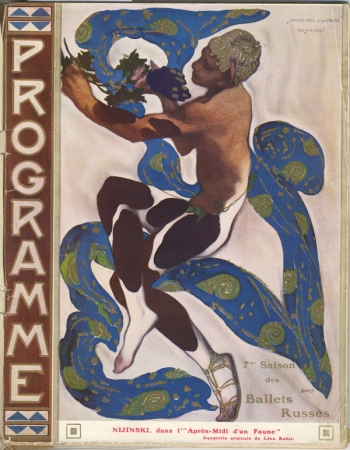

And here next to it is the iconic Bakst design for Nijinsky's Faune (pictured below left, V&A).

Which we borrowed from the Hartford Atheneum. It is such a wonderful image. Perhaps I’ll take that to my desert island.

What is that stunning blue cloth? Was that used in performance? And he is wearing these strange piebald spray-on breeches.

One must always remember that this was a programme cover illustration, so it’s not a costume design, it’s a fantasy image, a sort of storyboard. That cloth is an extraordinary blue, but nobody’s come along to say that was the actual kind of cloth they used for the veil in the performance [the Faune keeps a veil dropped by a nymph for his erotic fantasy], but the way Bakst uses it here gives a wonderful atmosphere of movement.

He has only one sandal on.

I know there is a company that did it one shoe on, one shoe off, but there is no evidence that Nijinsky ever did it with only one shoe. The costume of course on stage was up to the neck. It’s artistic licence, a piece of art commissioned for the programme.

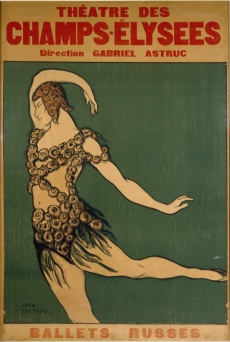

It's the same with the famous Cocteau posters of Nijinsky and Karsavina (the Nijinsky pictured above right, V&A). These are the 1913 versions of the ones originally designed for 1911 in Monte Carlo. So when the company had its first proper season with Spectre de la Rose. These again are artistic impressions, the costumes weren’t quite like that.

Now this is one of my favourites - a costume Niiinsky used to dance the L'Oiseau d'or pas de deux in (pictured right, V&A). It weighs four times the amount of the average Bluebird costume now. It is very, very heavy, with all that decoration and faux pearls, and to me the idea of somebody trying to dance incredible choreography in that makes me realise, my God, he must really have been an astounding dancer to dance at all in that, let alone make such an impression.

Now this is one of my favourites - a costume Niiinsky used to dance the L'Oiseau d'or pas de deux in (pictured right, V&A). It weighs four times the amount of the average Bluebird costume now. It is very, very heavy, with all that decoration and faux pearls, and to me the idea of somebody trying to dance incredible choreography in that makes me realise, my God, he must really have been an astounding dancer to dance at all in that, let alone make such an impression.

Every single picture you see of Nijinsky dancing, he has these fancy hats on, plumed, jewelled, and so on. He was dancing at top speed in these amazing headdresses. Then you see all those astonishing headgear worn in Le Dieu Bleu.

Yes, the headdresses for that one were designed for children - we forget how often children took part in these productions. Later on you get Boutique Fantasque where they got their children from the Italia Conti school - we’ve got a receipt on show for that in this exhibition.

And here is the set drawing for Le Dieu Bleu (1912). Which must have been one of the most amazing visual things ever.

Visually it must have been stunning, but probably choreographically pretty ghastly. I love the bit in the Herbert Ross Nijinsky film where Fokine and Bakst are talking, and Fokine says to Bakst, You’re trying to ruin my ballet by overdesigning. I think it was probably one occasion when they didn’t collaborate happily, and it became much more of a visual spectacle, more like a 19th-century ballet than what one thinks of as a Diaghilev work.

Sometimes actually it’s the non-successes whose materials survive better.

Yes, and it can colour one’s impressions in a different perspective when one is thinking what ballets one would like to have seen. There’ll be something that doesn’t look visually very interesting but you later discover the choreography was innovative and exciting. It is quite difficult to strike that balance.

I wonder whas Diaghilev would think about the fact that what remains of his ballets are only the permanent things, and the animating element, the invisible glue - the choreography, the atmosphere, is perished.

I think he would have been frustrated about that, but he would have been quite excited that the music and ideas generated so much other choreography, though.

The 182 choreographic versions of the Rite of Spring?

Yes, exactly. That’s probably the sort of thing that would have fascinated him.

Did you just put the word out around the world about this exhibition three years ago?

We did on this case, but most people we didn’t in the end borrow from. It’s wonderful knowing how much there is out there - people have become exciting in the Ballets Russes, and it’s very collectable now. There have been so many different exhibitions over the past two years about the Ballets Russes, I thought we would be the grand finale - but in fact the Australians are doing one after us. Yes, there are auctions that surround the exhibition now, and in a sense they do go hand in hand.

I presume Britain must have become a useful receiving house for materials, London having played a major part in the touring of the company.

I think Britain always acknowledged the heritage of the Ballets Russes from the start. Other countries rather discovered it later. There is a direct lineage, with Marie Rambert, Markova and Ninette de Valois coming directly out of the Ballets Russes, so I think there has been that interest here from the start, and we did get into collecting it in a big way. The French do have some remarkable material. I think they’ve become more interested in it than they were. There was a major exhibition in 1979 oriented very much towards paper works, but wonderful things in it, but end of last year and start of this year there was a remarkable costume exhibition from the Russian operas, partly based on the fact that in the 1990s they discovered in the Paris Opera a number of walk-on parts were actually still using costumes created for Diaghilev productions. It was fascinating.

Were there some disappointing countries who didn’t handle it right? It’s easy to say with hindsight, of course, but Russia obviously, because of politics?

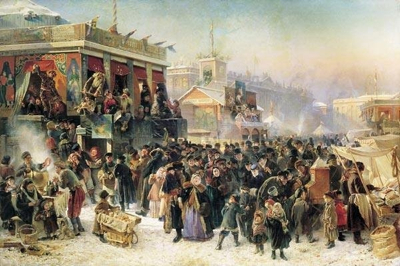

Well, it’s remarkable how much is tucked away in Russia, probably was hidden and rather escaped. But they are urgently reclaiming it now, and they are the biggest buyers nowadays of the items at auctions. A number of Russians were very willing to help us, but the trouble was most of what they were offering was duplicating what we already had. I think there are changing attitudes coming through, and we’re all realising that if we work together we’ll find out so much more. We incorporated some of the images into our audiovisual presentation, to give some context of Diaghilev's world of art. (Pictured, Konstantin Makovsky's Shrovetide Festival in Admiralty Square, 1869, which inspired Petrushka, © Russian Museum, St Petersburg)

Well, it’s remarkable how much is tucked away in Russia, probably was hidden and rather escaped. But they are urgently reclaiming it now, and they are the biggest buyers nowadays of the items at auctions. A number of Russians were very willing to help us, but the trouble was most of what they were offering was duplicating what we already had. I think there are changing attitudes coming through, and we’re all realising that if we work together we’ll find out so much more. We incorporated some of the images into our audiovisual presentation, to give some context of Diaghilev's world of art. (Pictured, Konstantin Makovsky's Shrovetide Festival in Admiralty Square, 1869, which inspired Petrushka, © Russian Museum, St Petersburg)

In this room we try to look at the big challenge of choreography and movement. It’s intended to look like backstage, with the paint-table in the middle. We realised that a lot of our visitors would have no idea what choreography is, so we have video here of Richard Alston creating a minute of choreography.

But up there, not looking very exciting, is Nijinsky’s own notation for his choreography for L’Apres-midi d’un faune. This is the one the British Library disbound for us so it could be read. It looks like music but it’s in Stepanov notation, a variant, which looks very like music. Nijinsky writing it down in his own hand, when he was interned in Hungary.

That is a fabulous treat, stunning.

And here is the Picasso portrait of Massine, and this case is actually music notation, all Stravinsky's own manuscripts - Les Noces, Firebird, and Pulcinella, and that score was actually was actually given to Picasso and they worked on it together.

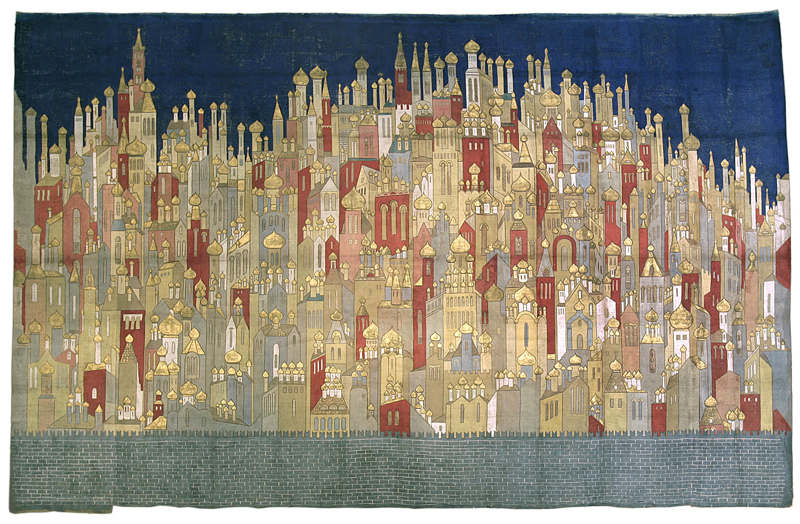

And now for the cloths - oh boy, what a sight.

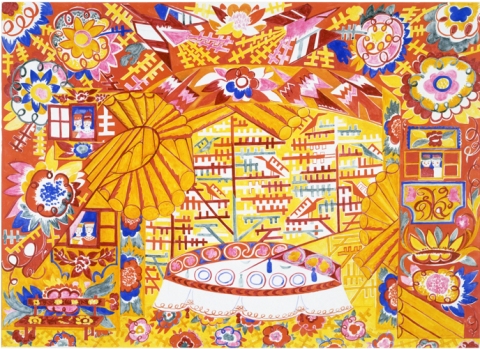

The Firebird cloth by Natalia Goncharova. We have quite a few cloths in the V&A collection but this really is the star, this is the 1926 version. You look at this and you can see the nostalgia for Russia in it, and it is such a fit with Stravinsky's music. (The cloth pictured below, V&A)

And the Train Bleu cloth is a special one for what it represents. Quite an event: Cocteau scenario, Picasso frontcloth, Chanel costumes, Laurens set, Milhaud music, Nijinska choreography, but really just a light piece, fun and game on the beach, and four characters mucking about in beach cabins. This cloth was painted flat on the floor in 24 hours and next to it we have a reproduction the size of Picasso’s original sketch, which is tiny, and they had to enlarge it with the grid system. The cloth was originally for the 1924 Paris season when Le Train Bleu was premiered, but then it got used for other things as well.

And we have a souvenir portfolio of prints of the Picasso designs for Tricorne - a fairly informal arrangement to show the sort of theatrical designs just pinned on a board. And these are recostructions of the Parade constructions, and the designs and photographs from the original glass plates.

Now here is the Picasso Chinese Conjuror costume, where you see the replaced left side of the costume.

Did he design them to be heavily padded?

Yes, there is a strongly sculptural quality. I was told the other day that the decoration on it represents the intestines, so that when he swallowed the egg you really saw it going down the intestines.

We managed to borrow Diaghilev’s passport of 1919 from the Paris Opera. It has so many countries and visas in it. This map shows the extent of touring of his company - people don’t realise how much they travelled and I was determined they should.

One really isn't aware. Down to Sao Paolo and Rio de Janeiro, up to Seattle and Vancouver top left, lots of East Coast, and then through Europe, though it all stops at the Russian border, Bratislava, Berlin, Budapest. But totally colonising Spain, seemingly.

One really isn't aware. Down to Sao Paolo and Rio de Janeiro, up to Seattle and Vancouver top left, lots of East Coast, and then through Europe, though it all stops at the Russian border, Bratislava, Berlin, Budapest. But totally colonising Spain, seemingly.

This was during the war, 1918 particularly, when they were stuck, and went round lots of smaller places. (Photo right by the dancer Idzikowski of touring in Spain.) It was Paris, Monte Carlo and London that they put the premieres on, but all these places would be bread-and-butter work, like any touring company.

Now as we move into the next part we need to be reminded about the end of the war, and the actual atmosphere this was all happening in so we have here a war picture, a Wyndham Lewis. You do need reminding about the real world they were operating in.

Next to Diaghilev’s Mitsouko perfume bottle. Some of the costumes appear to be made of cardboard at this stage. Is that wartime economy?

I have been told that it was because he was poor, but I don’t think that is so. I think this designer Mikhail Larionov was experimenting with Chout [a 1921 ballet composed by Prokofiev] to see what he could do, with all these collaged materials. (Pictured, the Buffoon's Wife costume from Chout)

I have been told that it was because he was poor, but I don’t think that is so. I think this designer Mikhail Larionov was experimenting with Chout [a 1921 ballet composed by Prokofiev] to see what he could do, with all these collaged materials. (Pictured, the Buffoon's Wife costume from Chout)

And here we have a case of company papers - for instance, Markova’s little handwritten receipt for her shoes in La Chatte, which you see orders them “with rubber”. She tells us in the John Drummond Diaghilev documentary that she insisted on it because the floor was slippery. And here's a note with flowers from Diaghilev to [his dancer] Felia Doubrovska, thanking her for the “exquisite festive delicacies”. I think this was when she got Balanchine to make some goodies for him, but as a diabetic man it would probably have been a disaster for him. But he did like his sweet things. And that's the accounts book for the Ballets Russes 1913 season documents all the expenditure for 1913. Later on we have Diaghilev’s penultimate hotel bill, for 2,118 lire at the Hotel des Bains, Venice, where he died rather suddenly of blood-poisoning in August 1929.

This kind of paperwork brings to the fore the sheer industriousness behind it, the real lives, the kitchen story. Everything handwritten.

And communication by telegram. A Croydon aerodrome receipt. Today it’s all electronic, all vanishes.

And now in this section we’re trying to evoke Diaghilev’s status in the cultural world. So this central cabinet started with the famous dinner at the Majestic Hotel. Proust writes about it. [The wealthy English patron] Sydney Schiff, who was the sponsor of the company in Paris, mounted a post-premiere dinner in 1922 where he invited the five most significant men in European modern arts to sit down to dinner with him. Picasso, Stravinsky, Diaghilev, Proust and James Joyce. So in this case alongside the Picasso costumes and Stravinsky music we have original MS and typed proofs of Joyce's Ulysses, Proust's A la recherche du temps perdu, and because Schiff also sponsored T S Eliot, The Waste Land. The chances of you seeing all these in one case ever again are extremely remote.

How do all the lent items get to you?

They're always accompanied by a courier. Sometimes we’ll install immediately, sometimes it would be put into store for a few days and the courier would return to supervise installation. You have to plan everything in one, but as the objects come in it’s an amazing jigsaw timetable. When you put in a lone object, once it’s installed you will not open that case until the courier returns to take it out. So you have to plan all the installation around that in advance. And if you have three couriers for one case it’s someone’s job to get them all together.

And is there a massive insurance policy for millions of squid?

It’s government indemnity.

Do you have to fulfil all sorts of conditions for loans?

There is always a condition report attached to any object. And you are given the report when you get the object; you go through it carefully, and draw attention to any change. Say it says one drawing pin hole and you see four, you draw attention to it. It is why we and most major organisations have a courier to do the handling. With our more fragile costumes we always have a costume curator on hand.

Are there many very valuable objects here?

Are there many very valuable objects here?

Perhaps not million-quid objects, but some of the costumes are worth six figures - particularly the Matisse probably. These four from Le Chant du Rossignol (pictured, the Mandarin, 1920). They are stars, so they’ve had the most conservation. The velvet fabric is so fragile. You see on the knees. Silk can shatter in your hands. The mourners are in an ivory and really really deep navy.

And there are two Goncharova Les Noces costumes, which we borrowed. And here is an animated reconstruction of the Pas d’Acier set, a Constructivist design Georgi Yakulov created with Prokofiev for the original ballet planned in 1925. This reconstruction was made for her PhD by Dr Lesley-Ann Sayers, who wanted to know what Yakulov was intending before the actual staging of it a bit later, and she tried to get back to the original intentions before Massine was brought on board in 1927. The collaboration of Prokofiev and Yakulov started in the mid-Twenties much on the idea of celebrating the new golden age of the early Soviet Union, but then conditions were rapidly changing under Stalin, so it could no longer be the optimistic experience originally intended [the Massine production mounted by Diaghilev was more of a satire on the USSR]. We have some photographs of the production. Princeton University mounted a performance afterwards based on what she researched of the original.

It is so rich and varied, this material, yet it is coherent - did you think this all up?

No, we were a team. I have a co-curator in Geoffrey Marsh who is very good on the contextual side, so I put in the dance side and he was more on the context. Then Tim Hatley designing the concept and the AV work - for which we had Howard Goodall and Richard Alston among the contributors.

So challenging because you had to address to many aspects - every aspect of civilisation. Theatre, music, art, dance, ideas, politics, writing, eras, and even commerce.

So challenging because you had to address to many aspects - every aspect of civilisation. Theatre, music, art, dance, ideas, politics, writing, eras, and even commerce.

Well, we do have to get a general audience interested in coming, so it isn’t just for theatre or dance audiences. We need a lot of people to come and see this, need to stimulate them and make them want to know more. The variety probably will manage to appeal to almost everybody. There is fashion here - from Poiret to Yves St Laurent - loads of photographs (left, the 1928 Liverpool tour, with Diaghilev second left and four of his stars, Serge Lifar, third left, and the ballerinas Alexandra Danilova, Felia Doubrovska and Lyubov Tchernicheva, V&A), and we even have some of the Ballets Russes marketing materials and souvenirs! Actually created for Cyril Beaumont’s shop. Little Nikitina and Nemchinova dolls and so on.

And we still have to reach Coco Chanel.

Yes, here is her case, with her Train Bleu costumes (pictured below left, with a photo of the London performanc alongside), and these are the Marie Laurencin costumes for Les Biches, and also the George Braque one for Zephyre et Flore.

They do look incredibly modern, the vest and pants approach. But what I think is important is the influence of the street coming on stage. It reminds me of is Katherine Hamnett designing "Strong Language" and saying you mustn’t say costumes, but clothes. I think that’s what you’re seeing for the first time there. [Chanel also designed new tricot tunics for the revivals of Nijinska's Les Biches and Balanchine's Apollo. She also paid for Diaghilev's funeral and burial in San Michele Cemetery, Venice. A recent film speculated on her relationship with Stravinsky.]

And here you have the stunning George Rouault Prodigal Son set designs for Balanchine's ballet which actually work as paintings too.

They do. And we whirl on to Balanchine's Le Bal and some designs by De Chirico - you see his Sylphide has these surreal and rather ornate wings. And there are the Yves St Laurent fashion collections inspired by the Bakst, Picasso, Goncharova and Matisse influences. You saw earlier we had the Paul Poiret fashions. We wanted the show the way all these influences spread out.

The thing you get from all of this is the tremendous exuberance of that company; the speed, vigour, colour and vibrancy of all their endeavours, and no wonder everybody picked up on them.

We wind up with four pieces of film: Tchernicheva in Thamar, film from the 1930s in Australia when they atually managed some colour filming, remarkably - then a 1937 staging of Le Coq d’or, which although it was different in fact as there was no cockerel originally on stage, you do get this wonderful sense of Goncharova’s costumes and colours on stage (pictured left, Goncharova's backcloth for Le Coq d'or). Then we come right up to date with film of Richard Alston and Akram Khan in different forms of collaboration. In terms of film we go from 1909 to 2007 or 8, so you have also a subtext of the history of film coming through all of this too.

We wind up with four pieces of film: Tchernicheva in Thamar, film from the 1930s in Australia when they atually managed some colour filming, remarkably - then a 1937 staging of Le Coq d’or, which although it was different in fact as there was no cockerel originally on stage, you do get this wonderful sense of Goncharova’s costumes and colours on stage (pictured left, Goncharova's backcloth for Le Coq d'or). Then we come right up to date with film of Richard Alston and Akram Khan in different forms of collaboration. In terms of film we go from 1909 to 2007 or 8, so you have also a subtext of the history of film coming through all of this too.

You’ve been working to this point for more than two years. How do you feel about all of this now?

Of course you go round thinking, Shame we didn’t get this, shame we didn’t get that. But I’m very encourage by the few people who’ve seen it already and have been impressed - because lots of people have said to me, Are you including this? No. Are you including that? No. So what are you including? And then there were others who said, I’ve seen a lot of Ballets Russes exhibitions, are you going to show us anything new? And I say, Yes, I am, and you need to come and see it. There is a totality of an exhibition, the way the items all work in conjunction with each other together. Every single item has been thought through, its place and purpose evaluated, and the associations it makes, and sometimes you need three of them to make a point, sometimes just one will tell the story. I also think when you see things mounted, you suddenly feel, How well that encapsulates the point we wanted to make.

A lot of Diaghilev exhibitions have been about going round and ticking things off a mental list of productions or artists. I mean, yes, we do have obvious sections: Bakst/Benois, Goncharova/Larionov, but a lot of the elements come together. Also I’m rather pleased that we mention an object or piece here and then it turns up again later in another section so people can acquire a familiarity or recognition of a work in various sections. And I think it helps to remind people that it wasn’t just about the first night of a production.

Your Hotel Majestic box is one of those individual strokes of context.

I think it is. And though some of the archival material has been used before in what I think of as library exhibitions, it’s exciting that we’ve used such a wide range of material - and I think this looks unlike any other Ballets Russes exhibition I’ve been to, which pleases me. This is all stuff that was created for a continuing purpose, not just an end in itself.

- Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909-1929 is at the V&A Museum, London till 9 January 2011.

- The comprehensive catalogue Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909-1929, edited by Jane Pritchard, is on sale by V&A Publishing

- A National Film Theatre season tribute From the Ballets Russes is at the British Film Institute, South Bank Centre, London, 26 Sep-12 Oct

- A Tribute to Dr Lesley-Anne Sayers examining her academic work on the recreation of Le Pas d'acier and Green Clowns is at the Laban Centre, London, 6 Dec

- English National Ballet have open public sessions rehearsing Ballets Russes-inspired works at ENB, Jay Mews, London, between 17 and 31 October

- Russell Maliphant's Nijinsky-inspired Afterlight is performed at Sadler's Wells Theatre, London on Tuesday and Wednesday 28-29 Sept

Watch Diaghilev performers Alexandra Danilova, Felia Doubrovska, Ninette de Valois, George Balanchine, Alicia Markova and Vera Stravinsky reminisce about Diaghilev:

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment