Concerto/The Judas Tree/Elite Syncopations, Royal Ballet | reviews, news & interviews

Concerto/The Judas Tree/Elite Syncopations, Royal Ballet

Concerto/The Judas Tree/Elite Syncopations, Royal Ballet

Shock power switch in new cast of MacMillan's brilliant last ballet

Another night, another cast, another Judas Tree (see first-night review below this) - and yet more proof of what a tough, durable, shape-shifting piece Kenneth MacMillan created in his last year of life.

Theories about what The Judas Tree means range from gratuitous misogynistic violence to a man exploring his inner divided self to Judas betraying Jesus in a jealous rage over Mary Magdalene. Last night Soares and his fellow cast members, dazzlingly led by Mara Galeazzi as the Woman who is their plaything, produced something much more akin to a lethal war by sons over their mother’s love, with the rivalry of the top two men further layering into the favourite, blithe son (Johannes Stepanek) and the harder, jealous son (Soares).

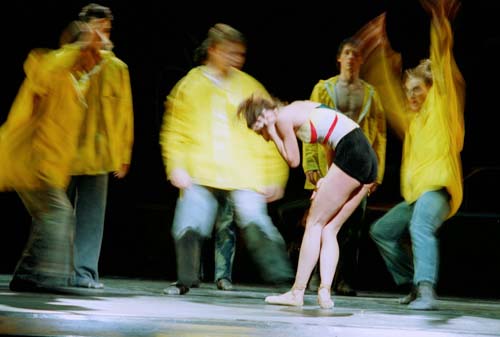

Galeazzi (a remarkable actress) used her statuesque elegance to stamp an almost intimidating female presence over the hellish building site, hammering her foot on the 11 men’s heads like a sow stamping on her piglets. As danced by her, the steps that resemble provocative sex-play or violent abuse became almost a reenactment of her giving birth to all these sons, a resilient fertility goddess.

The grappling duet between Galeazzi and Soares - the seething, wired first son desperate to break down his chill, disdainful mother - had an angst akin to Mayerling, and quite differently explosive to that achieved by the gentler, more bewildered Carlos Acosta with the vibrantly sexy, urchin Leanne Benjamin last week. Both interpretations came through as truly felt and penetratingly accurate psychological occurrences, plumbing profound theatrical ensemble acting qualities. And yet again that score by Brian Elias shone and rang and gleamed, a fascinating aural mirror for dark, suggestive mists between metallic clangs. What a pity that as yet this magnificent ballet, for its first two nights at least, hasn’t found the ovations it deserves. It may just take a younger audience to get it.

More bouquets for the super-versatile and dramatically irresistible Soares in the jolly vaudeville of Elite Syncopations. Sheathed in spandex stripes and a vast top hat, greasing down his hair vainly, and parading super-glam Marianela Nuñez in ragtime moves as slickly as a magician manipulating his lady assistant, Soares was an object lesson in how to enrapture an audience. In fact, this second cast for Elite was altogether more charming and fun than the first night’s, with Nuñez and Laura Morera both mistresses of flirtatious bottom-wiggling and Yuhui Choe and Liam Scarlett creating a sweet silent movie all their own in the "Golden Hours" duet. Concerto second time round underscores that it is pleasing, highly crafted, but not enriched with deep enough inventiveness or music (Shostakovich's second piano concerto) to match things like Ashton's Symphonic Variations or Balanchine's Symphony in C.

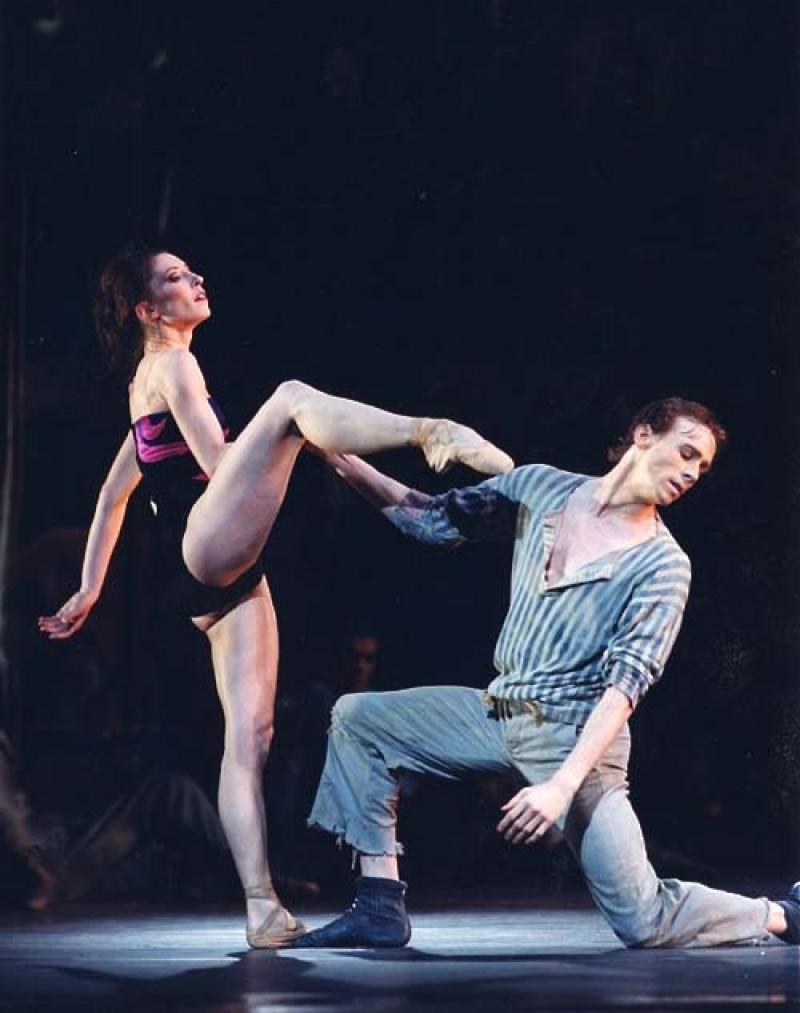

Right, Leanne Benjamin in The Judas Tree, photo by Asya Verzhbinsky

Right, Leanne Benjamin in The Judas Tree, photo by Asya Verzhbinsky

[My review after the opening night, 23 March:] With gang-rape, murder and clotted religiosity on the scenario, Kenneth MacMillan’s The Judas Tree easily makes enemies, but it is the boldest, most exciting ballet made in Britain in nearly 20 years. (Its pungency is sadly very likely the unwitting trigger for UK ballet’s subsequent retrenchment into either the twee or the woman-as-bendy-toy thing.) I'm still not sure it has found its time, though, judging by last night’s muted audience response to a rare new revival of this jawdropping 1992 work. And yet the performance had been inspired - inspiredly wrong, in a way, as it had rewritten the original power balance in such a surprising way that it had a scorching new heat.

Perhaps MacMillan, who would have been 80 last December had he not died backstage shortly after making The Judas Tree, would have taken this audience scowl as par for the course. The triple bill means well, most sincerely. It tries hard to represent him in his three extremes - the extreme classical decorum of Concerto, the extreme expressionist inwardness of The Judas Tree, the extreme light-entertainment of Elite Syncopations. All three delineate aspects of MacMillan’s towering talent, without the yoking quite capturing the man’s sheer theatrical devilry. It is not surprising that a Royal Ballet programme in its current safety-first regime would grab for Scott Joplin rags and vaudeville japes to supply a custard and apple-pie pudding after the black-hearted, salty slipperiness of The Judas Tree but the net effect is a cancellation-out, as if the Royal Ballet was determined to pin a smile on the louring, night-shadowed visage of its master of the dark.

An ill-lit, shadowy, metal-strewn, half-constructed building site is very MacMillanesque territory. From early on his career he took playgrounds as sinisterly magnetic places where the imagination touches the lawless child inside and runs away with its half-understood memories of loss, bullying, loneliness and cruelty. The Judas Tree is fascinating because of its blurriness, the sense that the choreographer himself is unpacking a container-load of unanswerable questions about male instincts and the fearful catalyst to their animal psyche that a single girl alone at night can inspire. It’s very East London now - as Jock McFadyen’s Canary Wharf designs underline (below left, McFadyen's Costa del Dogs, 1990) - and yet it’s also as formal in its choreographic rituals as MacMillan’s Rite of Spring three decades earlier.

Whether the allegory is about men hating women, or macho men hating gay men, doesn't matter - either works just fine as character stimulus to the explosions of leaps or tense grapplings that MacMillan so ingeniously creates with balletic vocabulary. The Foreman of the labourers appears to dominate his men in the dangerous sex game that emerges with the woman he brings into their midst. But the tables are rapidly turned by the woman’s unpredictable compliance and defiance, and by the ambiguous faerie spell she weaves over them, dividing their loyalties and whipping up their anxieties. By the end, despite the violent havoc, the female principle is the unquenchable one, the mocking one.

Whether the allegory is about men hating women, or macho men hating gay men, doesn't matter - either works just fine as character stimulus to the explosions of leaps or tense grapplings that MacMillan so ingeniously creates with balletic vocabulary. The Foreman of the labourers appears to dominate his men in the dangerous sex game that emerges with the woman he brings into their midst. But the tables are rapidly turned by the woman’s unpredictable compliance and defiance, and by the ambiguous faerie spell she weaves over them, dividing their loyalties and whipping up their anxieties. By the end, despite the violent havoc, the female principle is the unquenchable one, the mocking one.

Yes, this ballet is a strange, troubling experience - and this new casting taps its surprises further. Dancers often talk of the elasticity and range for individualising in MacMillan’s roles, and nowhere more remarkably than last night's performance. In the past Irek Mukhamedov stamped brute, brittle machismo onto the Foreman’s role, Judas the bad guy definitely, against the “good” Friend (who represents Jesus against Judas). But now Carlos Acosta took the Foreman’s role, an artist whose human compassion and grace can’t be disguised, and his villain’s clothes were stolen emphatically by the so-called good guy, the Jesus figure. Edward Watson is a thief on stage, he steals space, attention, significance; just by his stance, as crooked and stealthy as Acosta’s was straight, he turned this triangle of two men and a woman on its head. It became commedia dell’arte - not so much Jesus, Judas and Mary Magdalene (which I must say I've never found convincing), but Brighella the satyr of the night, poor gullible Pierrot, and the damnably elusive, alluring Columbine.

The dubious religious references at the end simply melted away, irrelevant. Last night's reading made more striking the theme of the treachery of sexuality within men; Acosta should have kissed Watson full on the mouth, instead of pecking his cheek, to convey the reason for the climactic violence, but never mind. It was a stroke of brilliance, this reading. Maybe it happened by intent - in which case it was inspired casting by Royal Ballet director Monica Mason - or maybe it was an instinctive mutual adjustment because Acosta can't help caring for women, and because Watson’s Brighella two nights earlier in the Nureyev Gala was still fresh in the latter’s mind. But how gripping to see a lethal power game rewritten in an equally combustible new form, without a step being changed. That’s great choreography, and great ensemble playing.

Little Leanne Benjamin is a lioness in the Woman's role - she roared back at the men in the yellow macs as they assaulted her and tried to snap her rubbery joints, wielding her pointe shoes like clubs, whacking back. Her mischievous dauntlessness was exhilarating, rather than gutting, not least because from the pit Barry Wordsworth was drawing a superb performance of Brian Elias’s overwhelmingly mysterious score, with its hubcap clangs, gamelans, glockenspiels and woozy Ravel-like strings.

For such strong meat Concerto is too sweetly lyrical, and Elite Syncopations too calculatedly ingratiating to make satisfactory starters and dessert - a better coupling might be Song of the Earth, or Gloria, to bring MacMillan's moving attempts on the sublime into the portrait of him. Still, in Concerto, which sets graceful academic classical dancing to Shostakovich’s second piano concerto, we had the balmy musical breeze of Yuhui Choe’s arms in the first movement, and the beautiful sureness of Marianela Nuñez’s poses in the ravishing adagio. Steven McRae busied himself smartly about the stage with Choe, and Rupert Pennefather stood rock-solid behind Nuñez. Happy piano-playing too from Jonathan Higgins.

For such strong meat Concerto is too sweetly lyrical, and Elite Syncopations too calculatedly ingratiating to make satisfactory starters and dessert - a better coupling might be Song of the Earth, or Gloria, to bring MacMillan's moving attempts on the sublime into the portrait of him. Still, in Concerto, which sets graceful academic classical dancing to Shostakovich’s second piano concerto, we had the balmy musical breeze of Yuhui Choe’s arms in the first movement, and the beautiful sureness of Marianela Nuñez’s poses in the ravishing adagio. Steven McRae busied himself smartly about the stage with Choe, and Rupert Pennefather stood rock-solid behind Nuñez. Happy piano-playing too from Jonathan Higgins.

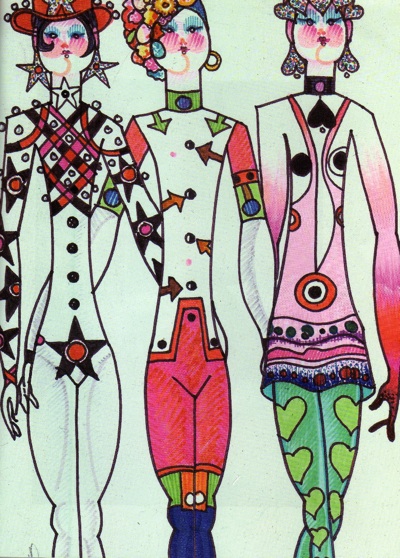

But putting Elite Syncopations on after The Judas Tree was clumsy. It’s MacMillan’s equivalent of Ashton’s Tales of Beatrix Potter - a basic primetime crowd-pleaser which is primarily about jolly picnic music and a big costuming event. If you like ragtime music, you get a lot of it, and Ian Spurling’s Pentel Pen-coloured leotards (his sketch, right), with their scribbled stars and naughty pockets on bum-cheeks, have a schoolkid freshness, but the choreography goes through very familiar motions. Not helped by last night’s lifeless enunciation of it by the cast - either chav vulgarity or cut-glass parody would do better, energy, teeth ‘n’ smiles, a bit of hard-sell, a bit of tipsy, knowing charm.

- The MacMillan triple bill is at the Royal Opera House, London until 15 April

- Jock McFadyen: The Landscape With Its Clothes On is on show at Clifford Chance, 30th floor, 10 Upper Bank St, Canary Wharf, London E14 5JJ till 23 April. A conversation between McFadyen and Rowan Moore, architecture critic of The Observer, at Clifford Chance 20 April

- See what's on at the Royal Ballet in 2010-11

- Read more Royal Ballet reviews

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Onegin, Royal Ballet review - a poignant lesson about the perils of youth

John Cranko was the greatest choreographer British ballet never had. His masterpiece is now 60 years old

Onegin, Royal Ballet review - a poignant lesson about the perils of youth

John Cranko was the greatest choreographer British ballet never had. His masterpiece is now 60 years old

Northern Ballet: Three Short Ballets, Linbury Theatre review - thrilling dancing in a mix of styles

The Leeds-based company act as impressively as they dance

Northern Ballet: Three Short Ballets, Linbury Theatre review - thrilling dancing in a mix of styles

The Leeds-based company act as impressively as they dance

Best of 2024: Dance

It was a year for visiting past glories, but not for new ones

Best of 2024: Dance

It was a year for visiting past glories, but not for new ones

Nutcracker, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - Tchaikovsky and his sweet tooth rule supreme

New production's music, sweets, and hordes of exuberant children make this a hot ticket

Nutcracker, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - Tchaikovsky and his sweet tooth rule supreme

New production's music, sweets, and hordes of exuberant children make this a hot ticket

Add comment