Kenneth MacMillan Died 20 Years Ago | reviews, news & interviews

Kenneth MacMillan Died 20 Years Ago

Kenneth MacMillan Died 20 Years Ago

Sex, death and jazz - a celebration of the ballet choreographer in all his moods

It's 20 years since the death, backstage at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, of a man who scripted high-wire emotions and extreme psychological states in a theatrical language that had widely been held to be the realm of sweetness and majesty. The choreographer Kenneth MacMillan brought the values of modern theatre, cinema and the sexual revolution to ballet, and his narrative daring remains unequalled by any choreographer in Britain after him.

Tomorrow the Royal Ballet displays a trio of MacMillan's ballets to mark the 20th anniversary of his death. He collapsed backstage on 29 October 1992 during the final act of an astounding performance of Mayerling starring Irek Mukhamedov. It was a shockingly dramatic night. The Royal Opera House chief Jeremy Isaacs came onstage at curtain call to announce the news and prevent applause. The audience, already wrung out by the performance of the harrowing ballet, dispersed in horrified silence.

A public that is now well familiar with his full-length ballet-dramas Romeo and Juliet, Manon and Mayerling will encounter three contrasting examples of MacMillan's versatility on the bill: a pure classical dance to music (Concerto) and an expressive elegy on the death of his friend, the choreographer John Cranko (Requiem), as well as a rarely seen gem of fierce storytelling from his early career, Las Hermanas, based upon Garcia Lorca's play, The House of Bernarda Alba, about the devastation wrought by the arrival of a virile man in a house of repressed women.

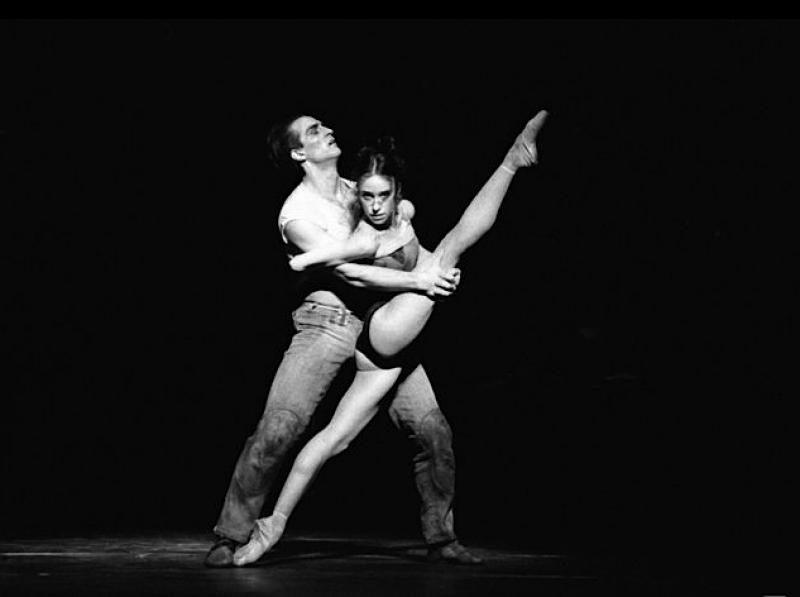

MacMillan's uninhibited balletic way with sex was one of his most noted qualities, bending and exploiting the traditional forms of balletic pas de deux and pas d'action in unmistakable narrative statements; unlike a classical pas de deux, which behaves rather like a baroque opera duet by using technical skills to circle expressively around a single emotional moment, a MacMillan duet will have its own story within, moving from flirtation to consummation, or from innocence to violence, or from repression to confession. In this new emotional nakedness in ballet, he was following his young man's passion for New Wave cinema as it leapt into modernity with the Fifties and Sixties; he even used balletic versions of freeze-frames and jump-cuts.

It was often in his short ballets that he exposed his most adventurous originality and took the greatest risks with his dancers

Only a handful of his most famous ballets are commercially filmed, but it was often in his balletic short-stories and novellas that MacMillan exposed his most adventurous originality and took the greatest risks with his dancers. Although a product of the Royal Ballet schooling (he was joyful to have joined the company just in time to get taken on the groundbreaking Sadler's Wells Ballet tour to New York in 1949 that made the company's global breakthrough), he was already showing a distinctly modern personality in his early choreography, with a strong inclination to explore the darkness of the human soul and disturbing subjects, influenced by his oppressively unhappy childhood and wartime upbringing.

One such was his early mini-drama The Burrow, which he made in 1957 when he was 29, swirling between myriad influences - from his very successful classical dancing career to his love of nouvelle vague cinema to his recent head-turning return to New York where major ballerinas seized on his talent. "I'm sick to death of fairy stories," he angrily told a newspaper. He fixed upon Anne Frank's wartime diary of concealment in her home, praying not to be discovered by the Gestapo, but created his own scenario influenced by Franz Kafka's final short story, The Burrow. He choreographed Frank Martin's taut music with a physical style that appears much more like modern dance than ballet in the film clips shown here of the original cast. The subject of persecution, of the community from outside or of the individual from within him/herself, would resurface constantly in his ballets throughout his career. In this extract uploaded by Nick Wallace-Smith from a television documentary about his career, MacMillan starts talking after 13 seconds of stills and silence. (The Burrow was last performed by the Royal Ballet in 1959.)

The central girl in The Burrow was a very young Canadian dancer, Lynn Seymour, who disparagingly described her own body as made of marshmallow, but whose uninhibited dancing became MacMillan's greatest inspiration. Little is preserved on film of this remarkable performer, but it was her dramatic derring-do that emboldened MacMillan, in The Invitation in 1960, to break all taboos in ballet and portray an Edwardian house-party at which a young girl is raped by an older guest. Aided by the contrast of the chilly Matyas Seiber music against Nicholas Georgiadis's lush period designs, Seymour's innocent urgency and raggedy-doll pliability let loose in the choreographer's mind new expressive possibilities in pas de deux that he would use to increasingly exciting (or disturbing) effect.

In this second extract from the television documentary, MacMillan, Seymour and Ninette de Valois (the Royal Ballet's director who spotted and encouraged MacMillan as a choreographer) talk about the impact of The Invitation, and that notorious rape scene - which de Valois originally asked him to cut out - is performed by its original cast, Seymour and Desmond Doyle. Again this clip starts with still photos for about 35 seconds. (The Invitation was last performed by the Royal Ballet in 1996.)

Next page: Las Hermanas, Concerto, Gloria, Manon, Mayerling, Elite Syncopations

Like The Invitation, Las Hermanas showed MacMillan shining a glaring light onto secret sexual desires. By 1963 he was working with the Stuttgart Ballet (run by his friend John Cranko), where Germany's expressionist tradition generated a densely emotional approach that he relished. He drew from Federico García Lorca's play The House of Bernarda Alba a plot showing the devastation wrought on a mother and her five unmarried daughters by the arrival of a virile man as a husband to the eldest. (The theme of sisters was a favourite of MacMillan's and he often portrayed siblings in intense relationships.)

The first four minutes of this recent Bavarian State Ballet trailer for an all-British mixed bill show glimpses of the wired, expressionist style he adopted in Las Hermanas. Ray Barra, who was the original man at the premiere, is their coach - the voiceovers are in German without subtitles. (Las Hermanas was last performed by the Royal Ballet in 1998.)

That MacMillan could also create lyrical musical ballet of purely classical beauty was proved by, among other works, his 1966 Concerto, set to Shostakovich's second piano concerto. Its slow central pas de deux was inspired by watching Lynn Seymour doing her warm-up at the barre - she had joined him as his ballerina at Berlin's Deutsche Oper Ballett, where he was now director. Here, in an extract from a Royal Ballet DVD, current principals Marianela Nuñez and Rupert Pennefather dance the movement. (Concerto was last performed by the Royal Ballet in 2010.)

MacMillan explored a more contemporary reworking of ballet movement in three creations where he used music that set words: two choral works and a song cycle, all associated with ideas of death or mortality. For these he infused his reaction to the compositions' own narratives, associations and images, rather than impositions of his own devising, and it led him to find more discreet ways to emote. If a pas de deux could not be that of two young people discovering love, or two adulterous lovers breaking up in tragedy, it could instead be a duet of graphically shapeshifting icons: a dove of hope in the hearts of embattled soldiers, a mother and son pietà. In Song of the Earth (1965), his two men and one woman became heartrending representatives of the journey from life to death; Requiem (1976) and Gloria (1980) both fielded almost painterly ensembles suggesting people protesting against threat, dreaming of liberation (images not so distant in intention from those of The Burrow, 20 or more years earlier.

Here is a (rather fuzzy) YouTube transfer by quillerpen from a television broadcast of the haunting trio from Gloria, using Poulenc's Gloria and musing on youth lost in war. It's performed by its original cast, Wayne Eagling, Julian Hosking and the exquisite Jennifer Penney. (Gloria was last performed by the Royal Ballet in 2011.)

The emotional discretion and more ideas-driven movement that MacMillan adopted in those elegiac pieces added a luscious sophistication to his vividly uninhibited approach to the choreography of sexual attraction. It was at its most astonishing in Manon (1974, to a romantic Massenet score), where the magnetic individuality expressed in this dangerous woman's solo, as well as suave and intricately mastered multiple partnering, are shown in this film clip of the superb two-part passage from Act 2 with Sylvie Guillem at La Scala Ballet last year. Guillem, when at the Royal Ballet in the early 1990s, had storming rows with MacMillan, as they debated who was the star - the ballerina or the choreographer. This clip made by gramilano shows that interpreter and creator together shine one phenomenal light. (Manon was last performed by the Royal Ballet in 2011.)

Four years later MacMillan gave male dancers a dream dramatic role to match the ballerinas' dream role of Manon, when he created Mayerling, about the drug-addicted, death-obsessed Prince Rudolf of the Hapsburgs. Lost in his fantasies, surrounded by women, buffeted by Liszt's beetling musical storms, Rudolf is one of the biggest roles in all ballet, and requires from its performers a scary psychological courage that very few can fully deploy on stage. Rudolf's story, and life, culminate in his suicide pact with Marie Vetsera, a ballerina role whose extreme sexuality and physical elasticity was created with MacMillan's muse Lynn Seymour in mind.

In this clip taken by Nick Wallace-Smith from a South Bank Show television programme made when the ballet was created in 1978, Kenneth MacMillan rehearses the first performers, Seymour and David Wall (whose voice is the first heard). (Mayerling was last performed by the Royal Ballet in 2009.)

Occasionally MacMillan could be found on the sunny side of the street - not often, but when he did the warmth and joyfulness were exhilarating. Though his last ballet was the harrowing The Judas Tree, his last piece of choreography was for the National Theatre's musical Carousel. And here is the ballerina Darcey Bussell introducing and dancing a number from Elite Syncopations, a 1974 party piece setting Scott Joplin ragtime jazz, which may well endure as long as his more characteristic nightmares. (Elite Syncopations was last performed by the Royal Ballet in 2010, and by Birmingham Royal Ballet in 2009.)

Listen to MacMillan talking about his career in 1983 in a Desert Island Discs radio interview with Roy Plomley on BBC Play it Again.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Onegin, Royal Ballet review - a poignant lesson about the perils of youth

John Cranko was the greatest choreographer British ballet never had. His masterpiece is now 60 years old

Onegin, Royal Ballet review - a poignant lesson about the perils of youth

John Cranko was the greatest choreographer British ballet never had. His masterpiece is now 60 years old

Northern Ballet: Three Short Ballets, Linbury Theatre review - thrilling dancing in a mix of styles

The Leeds-based company act as impressively as they dance

Northern Ballet: Three Short Ballets, Linbury Theatre review - thrilling dancing in a mix of styles

The Leeds-based company act as impressively as they dance

Best of 2024: Dance

It was a year for visiting past glories, but not for new ones

Best of 2024: Dance

It was a year for visiting past glories, but not for new ones

Nutcracker, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - Tchaikovsky and his sweet tooth rule supreme

New production's music, sweets, and hordes of exuberant children make this a hot ticket

Nutcracker, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - Tchaikovsky and his sweet tooth rule supreme

New production's music, sweets, and hordes of exuberant children make this a hot ticket

Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake, New Adventures, Sadler's Wells review - 30 years on, as bold and brilliant as ever

A masterly reinvention has become a classic itself

Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake, New Adventures, Sadler's Wells review - 30 years on, as bold and brilliant as ever

A masterly reinvention has become a classic itself

Ballet Shoes, Olivier Theatre review - reimagined classic with a lively contemporary feel

The basics of Streatfield's original aren't lost in this bold, inventive production

Ballet Shoes, Olivier Theatre review - reimagined classic with a lively contemporary feel

The basics of Streatfield's original aren't lost in this bold, inventive production

Comments

Elite Syncopations was in

Thanks, Mijosh, amended. I

Gloria is danced to music by

Of course it is, thanks,

It's unlikely that

BRB danced "The Burrow" in

Great article but why,

I agree about Anastasia, even