Survivor, Hofesh Shechter & Anthony Gormley, Barbican Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Survivor, Hofesh Shechter & Anthony Gormley, Barbican Theatre

Survivor, Hofesh Shechter & Anthony Gormley, Barbican Theatre

Is it possible for a show with 200 drummers to be a damp squib? It is now

Empty vessels make the most noise. That pithy old aphorism floated into my head a scant few minutes into the much-heralded new work by the undoubtedly talented, but here way off-beam, Hofesh Shechter. And again, a few minutes later. And again, and again, as something like 200 drummers filled the stage and bashed away in earnest polyrhythmy. At the end of the 80 minutes my watch was worn with checking.

Survivor is its name, and I absolutely don’t mind being asked to survive din if it’s worth it, if it changes you. We had been kindly offered the option beforehand of earplugs but it’s surprising how tolerable 200 drummers drumming a few feet away is, probably because this was live sound. It’s the words that I find hard to survive. Niagara Falls of verbiage have spilled about the imminent wonder of this collaboration between Shechter and visual artist Antony Gormley, Shechter pushing further over into his life as a composer here than his recent fame as a choreographer, and Gormley having made some striking props and sets for other choreographers.

Some of the words occupy large spaces in the programme book, tracts of ineffable flatulence, describing Hofesh and Antony meeting emotionally in a special place and stretching everything to all directions where anything is possible. How lovely for them, but this is rather too well signposting the production itself, whose aimlessness is the more annoying for being evidently so very costly.

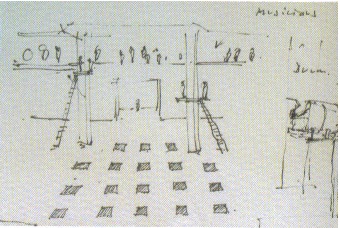

However, there is a star of the show to celebrate - and it is the Barbican theatre space. The vast majesty of the familiar stage is rarely exploited to its full extent as Gormley has done here (his sketch, pictured right), with a triptych of girder platforms high up in the middle and to either sides, apparently without support, on which sit many musicians, radiant in angelic light; and with gantries that soar upwards into the awesome 100ft height of the Barbican’s flytower, a flight thrillingly tracked by the eye of a camera attached. Dazzling distance effects are framed by Gormley’s metal scaffoldings and enormously high climbing ladders, the back brick wall and even the undercroft of the stage used. This is truly site-specific.

However, there is a star of the show to celebrate - and it is the Barbican theatre space. The vast majesty of the familiar stage is rarely exploited to its full extent as Gormley has done here (his sketch, pictured right), with a triptych of girder platforms high up in the middle and to either sides, apparently without support, on which sit many musicians, radiant in angelic light; and with gantries that soar upwards into the awesome 100ft height of the Barbican’s flytower, a flight thrillingly tracked by the eye of a camera attached. Dazzling distance effects are framed by Gormley’s metal scaffoldings and enormously high climbing ladders, the back brick wall and even the undercroft of the stage used. This is truly site-specific.

Never have the steel horizontal jaws of the hydraulic curtain been so aptly used as they open and close like a great ravening mouth on the light and sound within, swallowing hordes of musicians in one gulp, opening to reveal a man alone with a bath in another. The solitary man, immobile, is a strong, recurring motif, standing, lying, or hoisted on a wire horizontally like one of the sculptor’s famous statues being lifted up onto a roof, while a vast film image of torrential white water behind him seems to transport him into a waiting room for extinction.

But I found in this constant intrusion of the film screen into the stage space none of the evocative imperative of image-making of, say, Lucinda Childs' Dance or Merce Cunningham's BIPED - it’s cumbersome, and an increasingly intrusive cameraman fills time by projecting onto it what he’s filming, including the musicians, the dancers (pictured left), and inevitably us, the audience. This is pretty lame, I thought, pretty uninspired, as are the images of ocean waves, collapsing towerblocks or flak in the night over a war zone. It’s confusing how Gormley’s film contribution is so banal when the set construction is beautiful and revealing.

But I found in this constant intrusion of the film screen into the stage space none of the evocative imperative of image-making of, say, Lucinda Childs' Dance or Merce Cunningham's BIPED - it’s cumbersome, and an increasingly intrusive cameraman fills time by projecting onto it what he’s filming, including the musicians, the dancers (pictured left), and inevitably us, the audience. This is pretty lame, I thought, pretty uninspired, as are the images of ocean waves, collapsing towerblocks or flak in the night over a war zone. It’s confusing how Gormley’s film contribution is so banal when the set construction is beautiful and revealing.

Meanwhile the musicians, sometimes interspersed with six movement performers doing Shechter’s trademark hunched hokey-cokey, provide fine chiaroscuro sights perched high in their eyries with their drums and curvaceous cellos, but not especially gripping or pointed music. To compose 75 minutes of music has tested even such mighty masters as Mahler or Beethoven; Shechter’s style is to loop ribbons of melancholy folk threnody on the strings in between heavy drumming sequences climactically punctuated with tam-tams, cymbals and thrumming electric bass guitars.

This sort of sound he did much more tautly and emotionally acutely in his previous Political Mother, where he created a thrilling, forbidding polemic illustrating the manipulative capacity of noise on the human condition through some shattering dance ideas and visual shocks. Following that, Survivor has a sentimental, vacuous bombast to it - Lordy, it even has the performers la-la-ing "God Save the Queen". Is it possible for a show with 200 drummers to be a damp squib? It is now.

- Survivor is performed again tonight and twice tomorrow at the Barbican Theatre, London

- Hofesh Shechter's The Art of Not Looking Back is performed at Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, on 2 and 3 February

An extract of Shechter's Political Mother music below with an edited medley of his dance overlaid

Buy

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment