How do you know Wayne McGregor? Dance-goers with long memories might remember Wayne McGregor as the wunderkind who founded his own company and became resident choreographer at The Place aged just 22. Lovers of contemporary dance will be familiar with his company Random Dance, which boasts some of the best dancers in the business and periodically brings sophisticated, hi-tech pieces to Sadler’s Wells. Balletomanes will know him from his work with major ballet companies, including a long-term residency at the Royal Ballet. Cognitive neuro-scientists, anthropologists and other academics might know him as the choreographer most likely to call them up with a proposition for a new research project.

Plenty of other groups, including schoolchildren, visitors to science exhibitions, fans of TED talks, and careful readers of the New Year’s Honours list 2011 (in which he was appointed a CBE), will have had occasion to encounter this prolific choreographer, at 44 one of the most successful and influential dance-makers in Britain, if not the world.

I've wanted to talk to McGregor for a long time, not least because he’s clearly bursting with things to say. His programme notes, after-show talks and video interviews all reveal a man overflowing with ideas, which – perhaps uncharacteristically in the dance world – will come tumbling out in an articulate verbal torrent at the slightest provocation. He is now so successful that he is in the enviable position of being able to work in exactly the way that he wants, which involves a lot of collaboration with scientists in order to develop things like Choreographic Thinking Tools, computer aids to making dance "more creative". He loves to put technology in his pieces too: recent works like Atomos and FAR for Random Dance, and Machina for the Royal Ballet have featured such innovations as digitally printed costumes, light installations that interact with the music, and a giant robot that "dances" with the human bodies on stage.

This sort of thing is not to the taste of every audience member, or critic: and I must admit that the most recent McGregor pieces I've seen, like his Raven Girl (2013) and Tetractys - The Art of Fugue (2014), both for the Royal Ballet, have left me cold, and rather nostalgic for what I remember as the intense visual hit of his pulsing, kinetic Chroma (2006), or the tender, hypnotic Infra (2008).

When I talked to McGregor on the phone, he was down in Devon, where he has restored a 1935 house originally built for choreographer and Tanztheater pioneer Kurt Jooss. Next week sees Random Dance return to Sadler’s Wells for a major event called See the Music, Hear the Dance, in which composer Thomas Adès will play and conduct his own music alongside four dance pieces. McGregor’s company will perform his Outlier, set to Adès’s violin concerto "Concentric Paths", originally made for New York City Ballet in 2010. So I started by asking him about the process of remounting a work with a different company.

From everything I’ve read about the way you work, and the videos I’ve seen, you appear to be interested in getting dancers as individuals to develop the movements that they do – the movements should bear the stamp of that particular dancer’s personality. So when you’re remounting something on different dancers, as you’re remounting Outlier now, how does that work? Does it change anything about the piece?

Well, I’m not only interested in that; I think that’s one aspect of my practice. I am interested in personal physical signatures, but I’m also interested in my personal physical signature too. Choreography is for me a transaction of energy, so when I meet dancers that really inspire me physically, there’s a kind of a reciprocal dialogue: you invent the thing together, it’s like co-authoring. I think all good choreography is made in that way.

Well, I’m not only interested in that; I think that’s one aspect of my practice. I am interested in personal physical signatures, but I’m also interested in my personal physical signature too. Choreography is for me a transaction of energy, so when I meet dancers that really inspire me physically, there’s a kind of a reciprocal dialogue: you invent the thing together, it’s like co-authoring. I think all good choreography is made in that way.

Re-staging is not something I do a lot. I have people who go and re-stage my ballets all around the world for me. But that’s not something that I spend a lot of time doing because I like to be in the creative process, making something new. For me what’s really important is making now, not looking backwards – I’m not so interested in the past in that way.

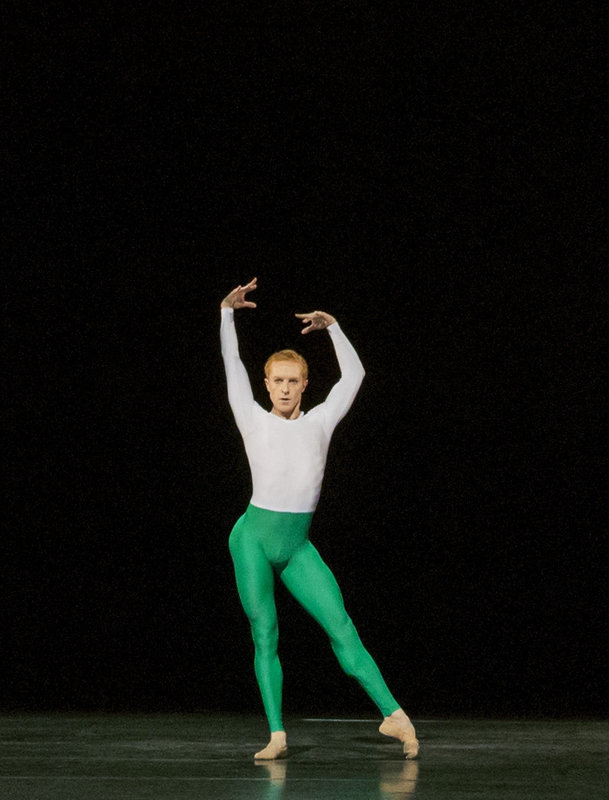

But I had a really lovely experience recently: we re-staged Chroma, which is a piece I made on the Royal Ballet, on Alvin Ailey, and it was such a thrilling kind of translation in a totally different way, a totally different dimension. I thought it would be really interesting to see what a piece [Outlier] which I made on NYCB in 2010 would look like on dancers that had worked with me for a long time and where that’s the only kind of work that they do: their physical glamour and their physical work is just that. (Pictured above right: a dancer from Random Dance in rehearsal for Outlier.)

Your Random dancers do inhabit your physical world. Do they inhabit your mental world as well? You have a very close relationship with them, don’t you, because you collaborate intensively with them? It almost seems like a kind of group therapy, as it were: you’re all interested in each other’s thoughts and responses and emotions.

I wouldn’t call it therapy. The idea isn’t therapeutic; it’s not about making people feel better about themselves. I think creativity is a collective experience, it’s a “we” not an “I”. Gone are the days when you had genius artists and they just gave this genius to other people as if the other people had nothing to do with it. It’s never worked that way in dance, because dance is an inherently collaborative art form. As a choreographer, you absolutely cannot do what you want without the reciprocity of amazing dancers.

I think we do ourselves a massive disservice in dance in not having looked at it as an intellectual art form. We have this idea, partly because of the past, of choreographers just coming and dancers just doing as if they’re not thinking. We know that dance is as much a cognitive act as it is a physical act. That’s why I’ve been very interested in physical thinking.

If it’s a cognitive act, how is it that you can inspire people to be more creative cognitively? Because we all have habits, we have habits of making. If I were to work with you in the studio, quite quickly I would start to understand what your physical habits were, and one of the things that choreographers have always been interested in is upsetting those habits, disturbing them, perturbing them, making them different. That’s why Merce [Cunningham] would use the I Ching, or some people would use music as a way of breaking their formal habits.

But those habits are not just in the body: they’re in the mind, they’re in the brain. And so if we can work with people to understand how we think about things, then we start to open up a whole range of other possibilities. And it’s not just for dancers, it’s also for people watching dance. When we watch dance we watch through certain filters and those filters are often very restrained, and yet we don’t root our watching in a responsibility to move that window, move that aperture a bit.

So that’s something you want for your audiences? You have an image in mind of how you want your audiences to come away changed?

Yes, but it’s not as glib as that. It’s just having audiences understand that when they’re watching something they’re watching with certain influences or priorities – some people would call them certain prejudices – and that it’s very hard not to watch like that. When we say we’re open waters and we’re just receiving what comes, it’s not actually true. I’m interested in how is it we might be able to just recalibrate that, so actually people get a different experience of watching, or at least know how it is that they’re watching. I think that could potentially be very exciting.

I’m not going to stop writing programme notes, but I realise the difficulty of the gap between the programme note and the thing that’s there

Do you ever do work-shopping with audiences?

Well as you know, we’ve worked with cognitive scientists over the last ten years. Actually we had this brilliant Wellcome exhibition about that work just before Christmas, one of the first times that the Wellcome Trust gave an artist a whole exhibition around cognitive work in creativity. We built this really beautiful resource, called "Mind and Movement", for children, which is using these cognitive principles to teach in schools the nature of creativity, and working phenomenally well.

And our next launch is, how is it we can prime audiences in a different manner?

It always makes me laugh when people – well, often it’s critics – do this. Clement [Crisp]’s a perfect example: he’ll read a programme note and then in the review he’ll moan about the fact that he’s read the programme note and that the dance doesn’t live up to what the programme note says.

What’s important to me about providing information is that audiences should take control of how they want to watch. Some audiences just want to watch totally naturally, they don’t want any information about it at all, they think the piece should say everything that it needs to say. I’m totally fine with that, I think that’s a great way of watching.

And some people – Luke Jennings is a perfect example of this – really like to steep themselves in the way the piece has been made, in the influences and some of the ideas, and use that as a tincture in which to watch. But you can’t do one and then say you wish you were doing the other. It’s quite difficult to say, “Well I’ve read the programme and I don’t want to own any of that information.” I always think I should put on the programme a hazard note: “Only to be read by people who are interested!” But then how do you prime audiences in a different way? I’m not going to stop writing programme notes, but I realise the difficulty of the gap between the programme note and the thing that’s there.

I would actually put myself in Clement’s camp as far as your programme notes go, which is to say that I love intelligent programme notes which give me lots to think about, but then it becomes the mind-body problem (which I know is what you’re thinking about too), that is, how do I jump from all the thoughts I’m having because of the programme notes to all the stuff I’m seeing on stage? Sometimes I can’t reconcile the two.

The programme notes are a fact of the process, this is how the thing was made, this is what we were thinking about when we made this piece. Those are undeniable facts. What the thing is, is a totally different thing, because what that is hopefully is something that transcends all of that. I’m not looking for a description of the programme notes on stage; otherwise I would have just written the programme notes. I’m not looking for a direct translation, I’m looking for something that has more poetry, more transcendence, that is more other. So the facts have made it, but the thing itself is its own thing. It’s challenging: I’ve certainly not in any way resolved it. I want to keep going with it

And one of the ways you might do it is to work with audiences, priming before they watch finding ways that that perhaps aren’t about reading programme notes. What other ways can we do it with scientists’ help. People think with different filters and that’s an interesting thing to experiment with. That’s what we’re going to be working on over the next few years.

Can you tell me any more about that? What are your initial approaches?

There are lots of ways in which technology can help. I’ve always been fascinated by the ways in which people look at things, like if you do retinal scanning, for example of an audience live. We did an experiment at Cambridge a few years ago with some cognitive neuroscientists who were looking at where the concentrations of interest are on a screen, which for me is the same as saying where are the concentrations of interest on a stage? They manifest themselves in terms of virtuosity. So we think that we as an audience – two thousand people watching something – have very different experiences of watching, but when you track people watching what you realise is that we actually have much more of a consensus of watching than we think. So people watch areas of concentration. So what interests me about that is what is the richness? Why are people attracted to those kinds of things? We’re not as promiscuous as we think about watching, so if we’re watching the same kinds of things, well what is the inherent interest in those things? Why is that happening? Is that a rhythmic thing? Is it something to do with virtuosity? Is that something to do with focus? Is that something to do with tension? And I think if you understand that, it might tell us something interesting about audiences.

I think we all we have a lot of received wisdom about things, and everyone always says: audiences watch differently, everybody’s got their own unique experience. But we’ve never really tested that – is that really true? What’s fascinating now with cognitive neuroscience is that we can access technology so we can actually test some of those things. We can actually do experiments.

So you’re still working with the cognitive neuroscientists at Cambridge?

Yes, at Cambridge, and a brilliant cognitive neuroscientist at San Diego. And also, one of the collaborations I’ve had for the last ten years is with a social anthropologist who used to be at Cambridge. He spends half his time with this amazing tribe in Papua New Guinea, where he’s practically the only white person they’ve ever seen, and then the other half of his time, he comes and spends time with this tribe that’s a dance company and works out the interpersonal relationships between groups.

When people are making, it’s as much a social, ethical problem as it is a creative problem. So it’s feeling embarrassed about making something – even for really elite artists – feeling that this thing they’ve made isn’t good enough, that this one they might be embarrassed about, that this one they’ve been pushed into because the person they were working with was stronger with the idea. Those are social attributes to creativity, and there’s a social attribute to people watching. I just find it endlessly interesting!

I’ve written this in some reviews, but other critics have also written it. And hearing you talk now, the same thing comes into my mind. You talk a lot about the cognitive aspect of things, about understanding and analysing et cetera, but you don’t tend to work that much from emotional stimuli, do you?

I don’t really understand what that means. Because we’re all sentient beings, right? We can’t divorce emotion from everything we do. I feel that some people talk about, describe emotion as if it’s they work with emotion in the same way that some people work with music. And I find that quite strange as a concept because everything I do comes from the inside of me and has massive emotional intelligence, or passion, or drive, or energy.

If you come and see me working in the studio, it’s not a dry intellectual process, I don’t work in that way at all. And the reason I think I inspire so many dancers is because actually there’s something really visceral and physical and emotional about that transaction of energy.

When we talk about emotion as if it’s about something which is separate from the way in which we are, I find that anathema really: I don’t understand what that is. I think there’s no such thing as an abstract body, I think bodies are all in some way narrative. I’m just interested in things that have multiple narratives.

It’s about preconceptions a bit, because as soon as you say you’re interested in science and technology people immediately have an idea of what that piece is going to look like and how they should respond to it. I often talk about exploring the technology of the body which for me is an emotional aspect, it’s not just a physical one I know you’ve written about me before that you feel that that my work can look sadistic. That seems to [reflect] a sense that if you do something that’s physically extreme, the default opinion is that it’s cruel, it’s not consensual, or there’s a sense in which it’s beyond “acceptable”.

There’s something really interesting about what do we mean by what’s possible in a body? For me, what’s possible in a body is always driven by emotion, but it often does things outside the ways in which most people experience what their tool, their instrument, their body can do. And that’s where often there’s a discomfort. It’s an interesting challenge.

Below: Royal Ballet dancers Tamara Rojo and Edward Watson in Wayne McGregor's Chroma

Of course, it would be naïve to assume that any activity could be totally divorced from emotion. But some choreographers might start from the premise of an emotion that they want the dancers or the audience to feel – that’s not the way you work, is it?

Well yeah, actually. One way I can explain that really clearly: say we’re working with a visual resource, say it’s a field, and we’re going to improvise a field. There’s a difference between if I ask you to imagine a field, and if I ask you to imagine a field that you remember from your childhood. One has emotional richness and attributes and that will change the way that you feel about improvising.

Emotionality for me is about how do you personalise everything that you do. The really brilliant people that I work with, I want something from them all the time. I want something of them, and because it’s of them, it has to be emotional, it has to have emotional resonance and value, otherwise they can’t work with the image or the image becomes really dry. So for me emotion is really there.

How people receive it is a part of the challenge, I think [related] to the kind of things that I do with technology, the kinds of of music that I choose, the colour palettes, the tonality of the piece, the ways in which bodies behave or misbehave or go to extremes which aren’t familiar. And all of these things perhaps distance you [the spectator] from emotions that you have experienced.

One of the things that’s fascinating is when I work with big international companies, big ballet stars – Mariinsky, Bolshoi, wherever they are – dancers who are unfamiliar with the work never worry about [this emotion question]. Because you’re in there physically doing it, it’s an embodied relationship that you have with dancers, it’s not an intellectual one – it’s not standing back thinking about it. It’s actually showing and doing and touching and feeling and moving, so it’s a very physical act.

I like dancers therefore who like that kind of interaction, who like to get in there and get messy. I love Natalia Osipova, I love Sarah Lamb, I love Edward Watson (pictured left), I love some of the younger guys like Tristan Dyer you know at the Royal [Ballet]. Obviously the dancers I choose at Random all have that or there’d be no point in them being with me, but yes, I gravitate to that.

I like dancers therefore who like that kind of interaction, who like to get in there and get messy. I love Natalia Osipova, I love Sarah Lamb, I love Edward Watson (pictured left), I love some of the younger guys like Tristan Dyer you know at the Royal [Ballet]. Obviously the dancers I choose at Random all have that or there’d be no point in them being with me, but yes, I gravitate to that.

I also gravitate to those dancers who aren’t worried about what they look like, so they’re not spending all their time looking in the mirror. I’m interested in those dancers who come into the studio, look me in the eye to say hello. I’m interested in those dancers who’ll have a chat with me in the corridor, I’m interested in those dancers who’re curious about things outside the Royal Ballet or the companies that they work with

Intellectual curiosity for me is as important as physical curiosity because I think they are the same thing. So if you look at Steven McRae (pictured below right): he’s got so many interests outside dance, so actually it feeds his brilliance inside dance. It’s no accident that those two things are connected. I would just love us as an art form to celebrate that more: to say that those exceptional artists are those who are really plugged into the real world, who are actually really curious and voracious, have an appetite for challenging themselves. When I get faced with somebody like that, like a Natasha or a Sarah, they’re saying to me look, this is possible with my body with the years of training that I’ve done, and this is what it releases in me. This is who I am.

And so this idea that I’m going in there making them do things which they’re not trained to do, or perhaps making them do things which are are extreme, is not true because actually a lot of it comes from them. They take pleasure in the fact that they’ve got so much phenomenal control over their bodies, that they’re elite artists, that they can do these really fascinating things and that becomes part of the vocabulary. That’s for me what makes something really alive and evolving and current and now.

And so this idea that I’m going in there making them do things which they’re not trained to do, or perhaps making them do things which are are extreme, is not true because actually a lot of it comes from them. They take pleasure in the fact that they’ve got so much phenomenal control over their bodies, that they’re elite artists, that they can do these really fascinating things and that becomes part of the vocabulary. That’s for me what makes something really alive and evolving and current and now.

From a spectator’s point of view too, the most interesting dancers are always those who you feel really have something to say.

Exactly. But that’s not just particular to dance, or art: it’s in every endeavour. The reason I’m interested in certain scientists rather than others is because it’s those who want to go an extra mile, those that actually have got this kind of synergy between a massive curiosity and a strength in what they’re already doing. That gives them the ability to think more abstractly, to be more imaginative, more creative, to look into the core of the things that they do.

Can you tell us about who you’re going to work with next, or who’s on your wish list?

I’ve got some amazing people, but they’re all going to be announced in good time. We’ve got a big announcement coming up about some amazing people who Random going to do their next project with.

I think there are so many interesting people. I want to work with people that are alive: that’s important to me, so I can have conservations. I want to work with people that come from areas that you wouldn’t imagine. I’d be fascinated to work with a geographer, I’d be fascinated to work with an engineer who might think about helping us work with objects. There’s so many different knowledge sets that I think could be useful to what we’re doing and that share alliances. That’s what’s exciting about where we are in dance and in the arts.

Our new building is going to help us do that. We’re getting this new building at the Olympic Park at the beginning of [20]16. It’s the most technologically literate building in Europe. It’s next to BT Sport, it’s right next to Loughborough’s elite sport science unit, it’s next to 400 tech companies. We’re going to do amazing making with artists, and let other artists make in really interesting ways outside of the confines of the structures that already exist.

Can you tell us more about the building?

It’s called Random Spaces. It’s a huge warehouse space with 13 meter ceilings, a huge industrial space. Have you ever been to Marfa in Texas? It’s this amazing little town, in which Donald Judd the American artist bought and converted army barracks into amazing studios and gallery spaces. It’s incredible, and it has this utilitarian, workmanlike feeling. That’s exactly what I want in this space, and inside the big cavernous environment we’re building random spaces – literally. Some of the biggest studios in London in a really interesting way, but also pods where we can work, interesting combinations of architecture and space where people will feel differently about how it is that they might make stuff. In February we’re launching the actual programme, a phenomenal programme which is really exciting. All I can say about it now is that I want to have lots of artists in there making their work. We’ll try as much as possible to take away the financial restrictions about renting space and give people opportunities, and at the same time have that building have a real resonance with its location especially in terms of education and creativity. There’s a lot of thrilling plans ahead.

Can we go back for a moment to the conversation we were having earlier about extreme movement looking ‘sadistic’? I take your point about your intentions as a choreographer, but I still feel uncomfortable about the ways in which these very extreme movements can look like gendered violence to an audience.

Can we go back for a moment to the conversation we were having earlier about extreme movement looking ‘sadistic’? I take your point about your intentions as a choreographer, but I still feel uncomfortable about the ways in which these very extreme movements can look like gendered violence to an audience.

If you look at the history of my work, my work is gender neutral. Very often, you see it with two boys. In Outlier (pictured above, in rehearsal), that section I made with Wendy Whelan and Craig [Hall] where she’s dancing in a really extreme way is done by two boys in the new staging with Random Dance. [The concern about gendered violence] is just an assumption again – but you know, ballet’s often gendered.

I worry about gendered violence when I see it in ballet too!

[I think your concern maybe] relates to this idea that there are certain rules in ballet, ideas that there are certain things that a body is allowed to do in the context of dance making. Personally, I think those rules are there to be shattered. If I’m someone who’s fascinated and obsessed with a body and want to explore all its dimensions, I don’t just want to explore its dimensions within a certain bandwidth. I’m looking to extend the bandwidth.

There’s something about that idea of “sadism” that takes the dancer out of the equation, and the intelligence of the dancer out of the equation. If you ever have an opportunity to talk about gender politics with Sarah Lamb (pictured right), her response to that is really interesting. Because she’s in the process of making that and she’s totally aware of what that thing is, she’s not doing it as if she’s an empty vessel, not understanding – one of her frustrations is that that’s perceived the way that it is when she’s contributed that, it’s not a man making it on her, she’s contributed to this thing being made and what she feels about it. The strength of things that she has to do in that Raven Girl duet, in terms of core strength, in terms of power, in terms of female power – it’s just that we watch it with a very particular filter. I think there are no rules, I don’t want to be constrained by rules.

There’s something about that idea of “sadism” that takes the dancer out of the equation, and the intelligence of the dancer out of the equation. If you ever have an opportunity to talk about gender politics with Sarah Lamb (pictured right), her response to that is really interesting. Because she’s in the process of making that and she’s totally aware of what that thing is, she’s not doing it as if she’s an empty vessel, not understanding – one of her frustrations is that that’s perceived the way that it is when she’s contributed that, it’s not a man making it on her, she’s contributed to this thing being made and what she feels about it. The strength of things that she has to do in that Raven Girl duet, in terms of core strength, in terms of power, in terms of female power – it’s just that we watch it with a very particular filter. I think there are no rules, I don’t want to be constrained by rules.

I read everything. I’m fascinated by what people write, I’m not worried. I love difference of opinion, I love reading stuff because it helps me get to understand the people that are writing, it helps me understand aspects of my work that I’ve got questions about. When you’ve got a really good critical press, actually you can start to have that dialogue. It gives me something to think about, and I think that’s what writing should be like!

Well, given that the critical press often feels pretty threatened in the current economy, it’s nice to have the support! Does the press "get" your work as much as you would hope?

I think it’s in waves, in cycles. You think someone’s getting it and then suddenly they write something you think is way off key. I think that’s part of understanding – it isn’t complete, it’s not a perfect science and nor is making choreography – if you’re going to take risks – because you don’t actually know [how it will turn out]. I feel I could make pieces that would be successful for audiences, I think I know how to do that, but that’s not what my interest is. My interest isn’t in preserving the status quo of my position as an artist: I’m trying to do things that I’ve not done before and take risks and challenge myself to see if that works. There’s a lot of learning in there. And reviews that are not 100% favourable, or a work which is critically not very well received, might be where the learning is happening.

I feel sometimes that where it’s more dangerous is – to take the Financial Times as an example – where lots of the people who fund the art form are being fed information about new work which is very negative and very risk-averse. That actually affects the whole economy. That’s where I think it’s dangerous because there’s no dialogue – there’s no space for a conversation with Clement. I love reading Clement, by the way!

What I find funny is when people say [my work] is too McGregorish as if I could be someone else! I kind of know what they’re saying, but I don’t think you’d get that with Murakami or Anish Kapoor. People wouldn’t say “it’s too Anish Kapoor”. It’s strange.

But these are all useful catalysts for thinking: prods that keep you inspired. If nobody’s writing anything, ignoring you, then you have no-one to talk to! I would love to think of a way with some critics to develop a better or more interesting or more useful way of having a critical dialogue. That could be a really great thing.

At the end of the day we’re just practising. All I’m doing is practising. I don’t really worry about what happened before because I think that can really restrain you. I just try to be really present, to be true to what I’m thinking and working on at that moment, and hope that that resonates with other people.

- Wayne McGregor/Random Dance will perform Outlier as part of See the Music, Hear the Dance at Sadler's Wells this week, 30 October - 1 November.

Add comment