theartsdesk Q&A: Russian Choreographer Boris Eifman | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Russian Choreographer Boris Eifman

theartsdesk Q&A: Russian Choreographer Boris Eifman

St Petersburg's creator of "psychological ballet" comes to the UK - prepared to face the critics

No choreographer so divides American and British critics as Russia's only international dancemaker, Boris Eifman. He's "an amazing magician of the theatre", according to the late, great US critic Clive Barnes. He "flaunts all the worst clichés of psycho-sexo-bio-dance-drama with casual pride," according to the masterly New York Times critic Alastair Macaulay.

Despite the glories of Russian classical ballet, and the mighty tyranny of the Soviet political system which fed the factory success rate of the magnificent Russian ballet system, that country has never produced individual choreographers of any sustained voice - except for Eifman. Buffeted, humiliated, attacked by political Russian critics for more than 30 years, he's also become accustomed to aesthetic attacks by free-minded Western critics who describe him as the Ken Russell of ballet. When he comes to London next month with his trademark big literary ballets - Anna Karenina and Onegin (pictured below by V Baranovsky) - he is prepared for anything.

However, what took me to St Petersburg last month was something that seems to me more important, even, than Eifman's unorthodox work having survived critical Blitzkrieg for half his life - something of real moment is happening in Russian ballet. He is building a stunning, hugely overdue new resource and combined theatre and school, aimed to generate new choreography and new dance versatility.

However, what took me to St Petersburg last month was something that seems to me more important, even, than Eifman's unorthodox work having survived critical Blitzkrieg for half his life - something of real moment is happening in Russian ballet. He is building a stunning, hugely overdue new resource and combined theatre and school, aimed to generate new choreography and new dance versatility.

Holland, Germany, Britain, America, France, Italy, even Australia - countries around the world have long outstripped the Russians in new choreography over the past 100 years. For the first time, it appears, Eifman's country is taking note of the desperate need to groom choreographers from their teens, and to give them somewhere to fledge their creative wings, all the stuff that happens almost routinely in the West but which has been virtually absent from Russia since, probably, the late 1920s.

Curiously, though, while the Mariinsky and Bolshoi ballets have continued to keep their priorities luxuriously appointed in classical stagings, it is the outsider who's finally aiming to address this cruel lack in Russian dance: its lack of ballet-makers for the new generations.

A year ago the Governer of St Petersburg signed off the start on the Boris Eifman Dance Academy, "to create an innovative system of dancing education in Russia of the 21st century", says the swanky brochure. The drawings and models show nothing remotely shy on the site on Lisa Chaikina Street, due to open on 1 September this year. It's a roomy four-storey building, with a high, private white wall at the front, airy glass transparency behind, designed by Studio 44. It puts the uncovering of talent first. The pupils will be sought out first from orphans, poor families and care homes. This is a social project to address the urgent Russian issue of neglected children, but also to help redress the recent collapse in the former Soviet network of hothousing children all over the land.

The Dance Palace appears even more confident in its modernity. The users will be burgeoning choreographers, who have not until now had a resource to prepare for performance, to understand the theatre, its rules and its possibilities. Eifman declares, "St Petersburg can and should be in the avant-garde - most innovative and distinguished ideas will be born here as it was in the time of Diaghilev, Stravinsky, Meyerhold, Shostakovich."

Eifman always has been an outsider, born in Siberia in 1946, who trained classically in Leningrad. Despite his subsequent job as a teacher in the hallowed Vaganova academy, he was never happy to settle in. In 1977 he left to do the virtually undoable in Brezhnev's Soviet Union - he formed his own company, the Leningrad New Ballet. After several formal renamings - signalling its steady move up the ladder of respectability - this is now augustly named the St Petersburg State Academic Ballet Theatre, which indicates how Eifman's once dissident company has become part of the establishment, just be hanging in there.

He's made around 40 full-evening ballets, a most impressive numerical achievement, sometimes based on literary classics - Anna Karenina (pictured left by Hana Kudryashova), The Idiot, Eugene Onegin, The Master and Margarita - sometimes on tortured historical personages - Tchaikovsky, Olga Spessivtseva, Rodin - always purple with emotion, Sturm and angst.

He's made around 40 full-evening ballets, a most impressive numerical achievement, sometimes based on literary classics - Anna Karenina (pictured left by Hana Kudryashova), The Idiot, Eugene Onegin, The Master and Margarita - sometimes on tortured historical personages - Tchaikovsky, Olga Spessivtseva, Rodin - always purple with emotion, Sturm and angst.

Eifman calls it "psychological ballet", the Soviet authorities called it pornography, before the onset of perestroika in the Eighties began to turn him into a folk hero. Since the fall of the USSR, Eifman - no longer harried, humiliated and pressurised to leave Russia - has gathered shelf-fuls of awards and recognition from his own country, the Order of Merit for the Fatherland, the State Prize of the Russian Federation, the Order of Peace and Harmony.

But whatever you think of his choreography, the man himself comes across in interview as simply extremely nice, normal, friendly and even cuddly (pictured by Nina Alovert below), and not nearly as oblique as many Russians meeting a British journalist. I doubt he puts a kopek of value on the national honours - just as he tries not to put a kopek of value on the bad reviews (which include mine). His audience, his public, have always come to see his work, and understandably for him, in Russia, this has been his validation.

But England... He is worried. He is bringing two of his storyballets over, two narratives of love-tragedy, Anna Karenina and Onegin.

St Petersburg can and should be in the avant-garde - the most innovative and distinguished ideas will be born here

ISMENE BROWN: You get very different critical reactions to your work. Some think you're magnificent, others think you're dreadful.

ISMENE BROWN: You get very different critical reactions to your work. Some think you're magnificent, others think you're dreadful.

BORIS EIFMAN: I do take it hard, sometimes. But the great critics, Clive Barnes, Anna Kisselgoff [former New York Times critic], the older critics, have accepted my art favourably - and this calms me down, makes me feel I'm doing right. But you see critics suppressed Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Tchaikovsky - you must take your example from them and carry on, despite the fire. Not everybody can admire my work, I know my own audience - my theatre is for people, not for critics.

I had this all from the start when I was being humiliated even by Soviet critics, and it was only the audience, the public who reassured me and helped me go on. The audience accept my work, and if my type of theatre is necessary for them, that's the only reason my company has existed for 35 years. My art is very emotional. Not everybody is ready to open his heart to it. A lot of people just want to be entertained, to say, "interesting", and go home. My performances, though, do require a lot of energy in response from the audience. A lot of people want this deep emotional shock, but others are not ready, and they close their hearts.

Above, the Anna Karenina dream sequence, pictured by Hana Kudryashova

Above, the Anna Karenina dream sequence, pictured by Hana Kudryashova

I don't intend to create a pure ballet troupe - it's theatre that I'm creating

Sometimes it's also a national difference. The British are more reticent about big emotions, you might say.

That's why I'm very nervous about London. I want people to come and see my productions, and I want the British public to get a new idea of Russian dance. I know they love [the Bolshoi chief] Yuri Grigorovich's ballets. I think they should love my art, because it's one bloodline, emotional, expressive. I'd like them just to come!

What are the qualities that you value in what Russia has brought to ballet?

I think the Russians added something very emotionally deep, with soul, to ballet. The Americans, for instance, and the British, they think and then they dance. But Russians, they dance first and then they think.

For you death, suffering, guilty love - these are the big passions you have in your works above all.

These are the themes of world literature. Shakespeare is built on them too. I only inherited them. I only took what Shakespeare and the old dramaturges and great writers did, and I take them for my own theatre. I don't intend to create a pure ballet troupe - it's theatre that I'm creating. Life itself is a mix of tragedy and farce. I try to put all these things into my ballets.

Who do you admire most in past choreographers - who would you consider your ancestors, your bloodline?

Of course, Marius Petipa, creator of St Petersburg ballet. Of course, Yuri Grigorovich. And of course, Kenneth MacMillan at the Royal Ballet. Petipa gave me the sense of dance as being a means to create a big theatrical show - how the dances have a unique distinctiveness within the show as an art. Grigorovich taught me that using dance language you can present very deep and serious philosophical ideas on the ballet stage. And MacMillan's work are important for me for their spirit - works such as Mayerling and Manon are productions of their time, but on the philosophical level they feel close to me in their construction. Each has a well-known plot and around it is built a big production, and big character roles created, of of which has become something new, a creation of contemporary time. Ballet becomes part of the larger culture.

Is a narrative essential to you?

Yes, extremely important. but it depends what story. A story needs to come out of the soul of the person in it, and every character has their secrets. So when you say, Eifman likes telling stories, you must understand that it's not just literary plots that I like - it's the stories of human beings, stories of the soul. Always the literature or historical event is just the reason for making a big narrative production about the internal life of man, about the human soul.

I had no exposure to Western ballet, because I couldn't go abroad. This brought me suffering, but on the other hand I kept my identity

When you decided to start your company in 1977, what was happening in Leningrad ballet then? What existed, apart from the Kirov?

It was the height of the Soviet system. The peak of the authority and pressure of the Kirov and Bolshoi, they dictated the style and form of ballet entirely. Konstantin Sergeyev was director at the Kirov, Yuri Grigorovich at the Bolshoi. My company was to be an alternative to this.

You wanted to do something similar to Grigorovich at the Bolshoi but in Leningrad?

Yes. I wanted to create a repertory based on the traditions of Russian art but at the same create something new. I had no exposure at all to Western ballet, because I couldn't go abroad. On the bad side, this brought me suffering, but on the good, I kept my identity, because I didn't copy anything. I tried to create my own original language which would be close to my own soul and fantasy, and to those cultures that raised me.

There was no tradition of independent companies, was there? Was it difficult to set up?

Yes, of course. At some points I was being pressured to emigrate from Russia - they tried to shut down my company. it was a great struggle to have the right to be a free artist in our system.

Did you have to have approval for your subjects before you made a production?

Yes, I always had to present my ideas to a special commission before I could present a show to the audience. I had to do this again and again, three or four times they made me remake something.

You started with how many dancers?

20 or 30. They weren't from the Kirov, they weren't of high professional level because I didn't have much money to pay them, but using these dancers we created some interesting performances that won the audiences, gathered full houses. I'd use Pink Floyd music, other rock bands that were prohibited in Russia.

How did you find the money to support it?

How did you find the money to support it?

From the start, we were always a state company. There was no such thing as a private company. We toured the Soviet Union, and it was entirely from the box office. It was a new model for that period, because at that time all ballet companies were fully state-funded. We were creating not only new choreography but a new economic model which gave us independence as an artistic organisation. We did become, in a way, financially independent, but there was political censorship. (Right, Onegin pictured by Anton Sazonov)

Was anyone else trying to start independent companies in the '70s?

No. Ours was the first.

It's amazing that you had the idea and managed to achieve it.

Yes, that's true. At that time I had different offers from state companies, I was making ballets for the Kirov, the Maly, other companies. I was given the opportunity to become the choreographer with one of the major companies. But I realised that if I accepted their rules I'd get good dancers but I'd lose my freedom, because i could do only those works that would be dictated to me. So I chose freedom.

Were there other companies in the world that you used as a model?

They probably existed, but I didn't know of them.

Who supported you? You were breaking a mould.

I had one sponsor only in my life [he pointed to the sky].

But God gives you talent but not bread.

God gives us an idea, and the strength, and the gift. If you have all of that, you can start working to achieve certain goals. Not everybody can make it. But God gives you the chance, and you have to use it. You have to fulfil the gift you have. It's a great responsibility to God, to use this gift.

Who encouraged you when you were having difficulties?

I wouldn't say I got any encouragement. But I do like composing choreography, and I felt I had this gift from childhood. Of course, my development was very slow, in comparison with the rapid development of my colleagues in the West. I devoted a lot of time and energy just to struggle against the system and censorship, so unfortunately I think my development was slower than it could have been. But on the other hand, instead of being a sprinter, I became a marathon runner - the company is now 35 years old. I can work on the ideas I want to work on.

Who would you like to have seen working, among choreographers, people you never saw?

MacMillan, of course, and Jiri Kylian, John Neumeier, Maurice Béjart.

Did you ever see any Martha Graham? Her contract-release style seems to be indicated in your own language.

I've only seen video. But once things opened up in this country I saw a lot of things had been going on that I had been doing, that were close to my own creative ideas, though it was pure intuition. Movement that comes from emotion, above all. Martha Graham and I are very far distant from each other, but we are close in nature, which makes our choreographic systems similar.

When did you start to feel confident that your company would succeed?

I think when perestroika came in. It was the moment that our authorities started to treat me differently.

Above, Anna Karenina photo by Hana Kudryashova

They said it wasn't art at all because it was so unlike the soul of the Kirov Ballet

How were you treated before? Were they suspicious or what?

It was very bad. Especially from the Leningrad authorities. They tried to close me down. They suppressed me, and did all they could to get me to leave the country - they described me as a ballet "dissident", said my ballets were pornography and my art was heresy. It wasn't art at all because it was so unlike the soul and spirit of the Kirov ballet.

Was it the physical qualities that were pornographic, or the dissident approach?

It was because, they said, my choreography didn't reflect Soviet style and Soviet reality, which existed only in the Kirov style.

But you admired Grigorovich…

Not so much admiration. It's more because he was able to build very clear ballet constructions, he had the mind of a constructor and philosopher. Grigorovich and Leonid Jacobson were the two I found closest to me, Grigorovich's philosophy, dramaturgy and construction, and Jacobson's for its fantasy nature and improvisation. To combine heart and brain is important.

So when perestroika happened, you became a state company then, didn't you? That must have been a very important moment.

These changes were obvious immediately. They said Eifman was a standard-bearer for the new Russia. So the people who'd tried to demolish me as a dissident the year before were now parading me as a hero. The status and conditions of my company changed immediately, but we did face economic problems in the new conditions. We had to find a new way to survive. We started touring abroad for the first time at the end of the 80s. We started to make money for the company, but we had none for touring inside Russia since at that time there weren't any producers or impresarios to invite us around Russia. By that time I had good dancers and had to pay them reasonably, because any of them could have left for the West - like Baryshnikov. A lot of dancers left in that period.

There are no choreographers at all in Russia. Independent or not! It's a great issue for us

Can you explain why there are so few independent choreographers like you in Russia?

There are no choreographers at all in Russia. Independent or not! It's a great issue for us. It's not just the problem of Russia, though, it's also the case in the rest of the world.

But it's made a priority in Europe to find choreographers and develop them. You have this incredible tradition of ballet, and yet you have no real choreographic tradition. Is it just a different priority?

No, we have the same priorities. You see, I think the new generation of Russians have a different cast of mind. They want quick money, a lot of success, a good life. They weren't and aren't used to hard work. Choreography is hard work, and you never know if you'll be successful or not, if you'll get any money for it. That's why young people don't do it − they don't want to devote their lives to this profession. (Right, Onegin pictured by V Baranovsky)

No, we have the same priorities. You see, I think the new generation of Russians have a different cast of mind. They want quick money, a lot of success, a good life. They weren't and aren't used to hard work. Choreography is hard work, and you never know if you'll be successful or not, if you'll get any money for it. That's why young people don't do it − they don't want to devote their lives to this profession. (Right, Onegin pictured by V Baranovsky)

In the UK we have a lot of small choreographer-led companies. Is there a structure to allow or encourage this to happen in Russia?

They exist, of course, but unfortunately they're only doing commercial repertoire, and abroad when they tour they just show very poor-quality classics. You see people who, in a classical sense, are practically cripples, but they get commercial success abroad because they are "Russian ballet". They don't do modern art, they don't create, they don't search for new forms. I have two big projects right now - the academy and the Dance Palace, which will be a theatre, not just for my company, but also a home for young choreographers who will work with small companies, creating experiments, trying themselves out in this new field. I see that the state here does nothing like that, but I want to do this, in the name of youth. I never had the chance before to invite young choreographers to my stage, and still, when I present my ballets in St Petersburg, I pay a huge amount of money to rent a stage like the Alexandrinsky Theatre here for our performances. Once I have my own stage, my own rehearsal studios, then I'll start helping young choreographers.

You have the funding?

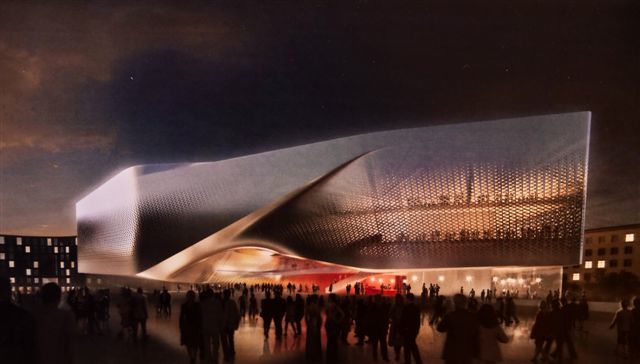

The city authorities are building the Academy, and there is some private funding from Moscow for the Dance Palace (architects' image, left).

The city authorities are building the Academy, and there is some private funding from Moscow for the Dance Palace (architects' image, left).

Do you talk to people like Baryshnikov, who built his arts centre in New York?

I know about it but I haven't seen it, but the things he's doing there are very important for art. He's a very creative person, and he will surely be developing choreography, musicians, directors, all creative theatre artists with his centre. It's very good work.

He and Mark Morris both wanted to create a New York centre to help choreography develop. Yours will be the first in Russia?

It will be the first institution in Russia with a serious aim to do this. Of course young choreographers do have opportunities but they're occasional. It's important to realise that the performances choreographers will give in our dance palace won't be commercial. As soon as a company invites a young choreographer naturally their first interest is commercial success, and this damages the choreographer's freedom to create. We will have a new programme every three months - it will be pure experiment, completely non-commercial.

How does a choreographer earn money here to eat, pay their bills?

Each one survives as best they can, in their own way. They work in different cities and companies, in showbusiness sometimes. Of course there are companies that only do modern dance. But I'm not talking about modern dance, which I think is a copy of Western traditions, I'm talking about the new generation of choreographers trained in Russian ballet who create ballet theatre on a large scale. Not only classical, but it must be full-evening - this is very important to me. Too many choreographers make small pieces, and nothing else. But this destroys their mentality, their ambition. They can't see where to go. They need to think about ballet-theatre.

Can you imagine opera suddenly stopping as an art, and only small opera pieces being made?

For instance, your Russell Maliphant and Wayne McGregor - I like their work, but it's all small pieces. Who will continue the way that MacMillan worked at Covent Garden? They need new, big productions in that theatre's traditions. Can you imagine opera suddenly stopping as an art, and only small opera pieces being made? It can't just become a concert art - it must be a theatre art. Covent Garden has 90 dancers - they should be working with them all. I think opera is developing in a good way, even the most avant-garde opera has a good dramaturgical base - but ballet? Little abstract compositions.

So you don't like Balanchine!

No, I like Balanchine, but I don't like it when everybody starts copying Balanchine. I don't understand why we must think only Forsythe and Kylian is good, while the Grigorovich, MacMillan, Neumeier, Eifman line is bad.

People don't say that!

No, but critics like to say, this is "avant-garde" - look at the reception of McGregor. I like his work, but let's talk about the future of our art, of ballet in theatre. Where is that future?

Can I ask you about your new creation, Onegin, which you're bringing to London? Your Anna Karenina is more classically presented, but Onegin is much more obviously contemporary in styling. (Right, Onegin pictured by Hana Kudryashova)

Can I ask you about your new creation, Onegin, which you're bringing to London? Your Anna Karenina is more classically presented, but Onegin is much more obviously contemporary in styling. (Right, Onegin pictured by Hana Kudryashova)

I was interested to try to take Pushkin's hero and present him in a modern context. To see how Pushkin's hero might react living in our time. And what Russia is today. How the values that were important in the 19th century have become more or less important.

So what did you find?

Well, the important spiritual, emotional side of the Russians has remained the same, they are romantics, they take a romantic view of life. But our epoch is much more pragmatic now, more materialistic, and those values are suppressing the spiritual ones. It's a great struggle that we see in Russia now. It's not a political battle, as some people say - I think it's a battle between God and evil. I'd say it's between one Russia which has a strong energy and morality, the Russia of Tolstoy, Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Tchaikovsky, and a new Russia of today, which is the result of the total collapse of moral values.

You really think so?

We see a new, free generation to whom materialistic values are much more important than spiritual ones. It's an endless metaphysical struggle. But materialism is winning. This is why we are losing our country. That's why we see no new choreographers, composers, writers. Through many centuries our country was based on powerful spiritual energy and moral questions. And the human was treated in our culture as a spiritual creation, not just a physical or material one. Unfortunately the devil is winning in Russia today. Freedom opens new possibilities to bring in different cultures, but the new generation has taken only the bad features of Western culture, when actually Western values are the base for all the world's civilisation, and could bring us so much.

- Eifman Ballet perform Anna Karenina on 3,4 April, and Onegin 6,7 April at the London Coliseum - then in Berlin, 19-22 April; Italian tour, 3-10 May, to Parma, Modena, Pavia, Milan; Moscow's Bolshoi Theatre Open-Art Festival, 22-24 May; Recklinghausen, Germany, 4-7 June

- Eifman Ballet website

Watch the Eifman Ballet's promotional trailer with extracts from several of his ballets

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Maddaddam, Royal Ballet review - superb dancing in a confusing frame

Wayne McGregor's version of Margaret Atwood's dystopia needs a clearer map

Maddaddam, Royal Ballet review - superb dancing in a confusing frame

Wayne McGregor's version of Margaret Atwood's dystopia needs a clearer map

Pina Bausch’s The Rite of Spring/common ground[s], Sadler’s Wells review - raw and devastating

Returning dancers from 13 African countries deliver celebrated vision with blistering force

Pina Bausch’s The Rite of Spring/common ground[s], Sadler’s Wells review - raw and devastating

Returning dancers from 13 African countries deliver celebrated vision with blistering force

Legacy, Linbury Theatre review - an exceptional display of black dance prowess

An all-too-fleeting celebration of black and brown ballet talent that demands a reprise

Legacy, Linbury Theatre review - an exceptional display of black dance prowess

An all-too-fleeting celebration of black and brown ballet talent that demands a reprise

National Ballet of Canada, Sadler's Wells review - see this, and know what dance can do

Yet again, Crystal Pite proves herself a ferocious creative force, alongside fellow Canadian exports James Kudelka and Emma Portner

National Ballet of Canada, Sadler's Wells review - see this, and know what dance can do

Yet again, Crystal Pite proves herself a ferocious creative force, alongside fellow Canadian exports James Kudelka and Emma Portner

Nobodaddy, Teaċ Daṁsa, Dublin Theatre Festival review - supernatural song and dance odyssey

Michael Keegan-Dolan’s genius guides us through death, separation and loss

Nobodaddy, Teaċ Daṁsa, Dublin Theatre Festival review - supernatural song and dance odyssey

Michael Keegan-Dolan’s genius guides us through death, separation and loss

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Royal Ballet review - big, bold and ultimately brash

It may be box-office gold, but Christopher Wheeldon's adaptation fails to find a beating heart down the rabbit hole

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Royal Ballet review - big, bold and ultimately brash

It may be box-office gold, but Christopher Wheeldon's adaptation fails to find a beating heart down the rabbit hole

Resurgence, London City Ballet, Sadler’s Wells review - the phoenix rises yet again

A new 14-strong company reviving a much-loved name is taking ballet to smaller theatres

Resurgence, London City Ballet, Sadler’s Wells review - the phoenix rises yet again

A new 14-strong company reviving a much-loved name is taking ballet to smaller theatres

The Mad Hatter's Tea Party, ZooNation, Linbury Theatre review - a joyous celebration of differentness

Kate Prince's hip hop take on Lewis Carroll is energetic, charming and moving by turns

The Mad Hatter's Tea Party, ZooNation, Linbury Theatre review - a joyous celebration of differentness

Kate Prince's hip hop take on Lewis Carroll is energetic, charming and moving by turns

Ballet Nights #006, Cadogan Hall review - a mixed bag of excellence

Gala enterprise, 12 months on, will be a stayer if it keeps up this level of excitement

Ballet Nights #006, Cadogan Hall review - a mixed bag of excellence

Gala enterprise, 12 months on, will be a stayer if it keeps up this level of excitement

theartsdesk Q&A: Nina Ananiashvili, founder of the State Ballet of Georgia

Bolshoi superstar who made her name in London returns with a new generation

theartsdesk Q&A: Nina Ananiashvili, founder of the State Ballet of Georgia

Bolshoi superstar who made her name in London returns with a new generation

Comments

So curious! Can't wait to see

Who cares what critics think