Wayne McGregor triple bill, Royal Ballet | reviews, news & interviews

Wayne McGregor triple bill, Royal Ballet

Wayne McGregor triple bill, Royal Ballet

Choreographer is as concept-heavy and content-light as ever in two revivals and a premiere

"My mission is to create new dance with new music and new design that is intimately plugged in to the world we live in today. I am motivated to make contemporary work that speaks of now and that is totally present-tense," Wayne McGregor explains in the programme note for last night's triple bill of his works at the Royal Opera House. It's the McGregor-speak that we have all come to know: a vanishingly tiny message wrapped up in obfuscatory verbiage.

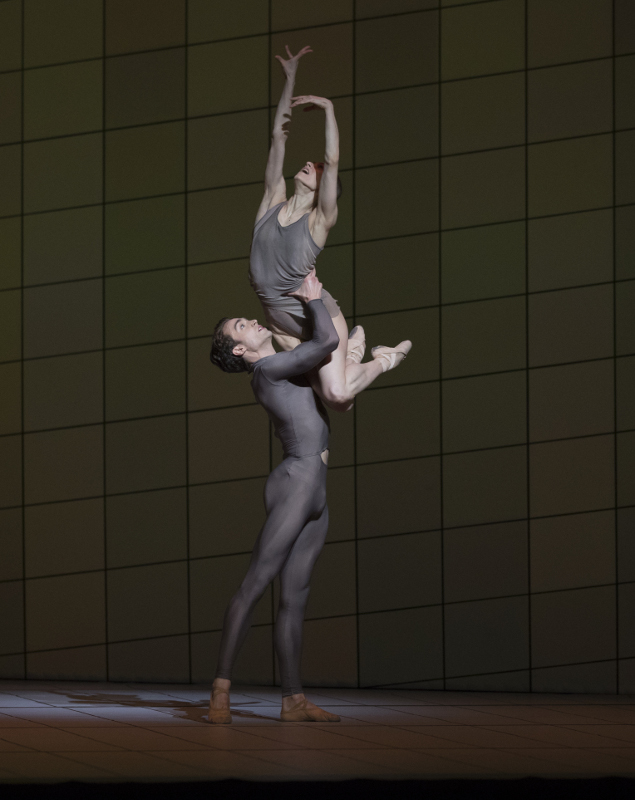

Last night's premiere, Multiverse, is very much a case in point. It starts well, with a brilliant, dynamic duet for Steven McRae and Paul Kay that plays with echoing, copying, synchronicity and syncopation in much the same way as Steve Reich's score does. It's Gonna Rain (1965) sets two tapes of the same track spooling and derives part of its unsettling impact from their gradual drift out of sync. The other part of its impact derives from the words "it's gonna rain" themselves, barely recognisable though they become: the cry of a street preacher about the great Flood. The piece dates from shortly after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and captures a mood of apocalyptic threat that is all too recognisable in the shaken-up world of 2016.

In Multiverse, the backdrop briefly features scrambled versions of images highly resonant for this theme of flood and catastrophe: refugees in small boats in the Mediterranean (main picture), and The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus by Rubens. For a stunning moment, I thought we were going to see something new from McGregor: a hard-hitting political piece about violence, exploitation, and rising waters, something like John Akomfrah's utterly brilliant Vertigo Sea (currently displayed at Turner Contemporary in Margate next to Turner's The Deluge). The programme notes by dramaturg Uzma Hameed reveal that these ideas were indeed present during Multiverse's development: the piece, it is implied, takes its cue from the way Rashid's fragmented paintings offer different perspectives, challenging notions of linear time and reframing monolithic historical narratives to expose the "cruelty and chaos" underneath.

In Multiverse, the backdrop briefly features scrambled versions of images highly resonant for this theme of flood and catastrophe: refugees in small boats in the Mediterranean (main picture), and The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus by Rubens. For a stunning moment, I thought we were going to see something new from McGregor: a hard-hitting political piece about violence, exploitation, and rising waters, something like John Akomfrah's utterly brilliant Vertigo Sea (currently displayed at Turner Contemporary in Margate next to Turner's The Deluge). The programme notes by dramaturg Uzma Hameed reveal that these ideas were indeed present during Multiverse's development: the piece, it is implied, takes its cue from the way Rashid's fragmented paintings offer different perspectives, challenging notions of linear time and reframing monolithic historical narratives to expose the "cruelty and chaos" underneath.

Splendid, potent stuff - but after that first duet, Multiverse offers no further hint that these themes are supposed to be its backbone. It spirals in on itself to become vintage McGregor: abstract dance, very much of the same kind as he has been making for a decade. There are a few touches of emotion that hint at narrative - people hanging their heads in despair, or looking up to the sky as if expecting rain - but mostly it's the same-old, same-old. The dancers' personalities barely shine through, the backdrop projections become symphonies in neutral colours, Moritz Junge's costumes - supposedly inspired by dragonfly wings! - are the usual greige underwear (pictured above right).

McGregor has heard this litany before, and will doubtless respond - as he does in the interview featured in the programme notes - that he doesn't see why he should be criticised for having a signature style or investigating the same themes repeatedly. But saying you are investigating something is no substitute for actually managing to convey the nature of that investigation to an audience without programme notes. Migration, climate change, colonial and gendered violence, the imperialism of the Western gaze, divine judgement on human sin - these are all vast, stirring ideas: a dance piece based on them should jump down your throat and leave you shaken. Perhaps it did just that for some people - but not me (nor the gentleman behind me who fell asleep and snored). More's the pity.

Chroma (pictured above), the first piece on the bill, was made ten years ago and was McGregor's breakthrough at the Royal Ballet. All those hyper-extensions, that contemporary score (Joby Talbot and the White Stripes), that hypnotic way McGregor has of inhabiting a pulsing rhythm, the leanness and power of those elite Royal Ballet bodies: all left a deep impression on me the first time I saw it. It seems tamer on second viewing, much less head-banging than I remember, and the shock of the new is gone after years of seeing McGregor's other work at the Royal Ballet. How fortunate then, for these performances, to have dancers from Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater on stage: they help to make the piece feel new, in that, having more contemporary training, they inhabit McGregor's movements very differently - with less surgical precision, but more feeling. The Royal Ballet's Calvin Richardson, clearly a new McGregor favourite, also adds verve, bringing the swagger, the sheer magnetism of a supermodel to his appearances: using his head like a seventeenth-century aristo on speed, he looks like he's in a different ballet to his more classically correct colleagues. More power to him.  Carbon Life, the programme's closer, is McGregor in a different vein: a rock band on stage, edgy costumes from Gareth Pugh, dark colours and bright lights. The opening ensemble number has a winning sense of style and energy: it reminds one that McGregor does quite a lot of commercial work choreographing music videos and the like. In fact, I felt that this particular number would look even better on a small screen, with beefed-up sound and lots of cutting to disguise the fact that the actual steps are fairly bland. The score, a series of pop songs with the odd instrumental number by Mark Ronson and Andrew Wyatt, had a seductive kind of poignancy even without Boy George, who sang in the 2012 premiere. I couldn't catch all the words, but there was mingled longing and anger at an absent lover, even the threat of violence. Little of it was picked up in the series of interchangeable duets which forms the middle of the work; my interest only revived towards the end, when Eric Underwood appeared looking both splendid and ridiculous in a kind of black Wonderwoman costume and pointe shoes (pictured above left) and the singers crooned "I need somebody to be nice, I need somebody to love me", and all was briefly daft and funny and fun.

Carbon Life, the programme's closer, is McGregor in a different vein: a rock band on stage, edgy costumes from Gareth Pugh, dark colours and bright lights. The opening ensemble number has a winning sense of style and energy: it reminds one that McGregor does quite a lot of commercial work choreographing music videos and the like. In fact, I felt that this particular number would look even better on a small screen, with beefed-up sound and lots of cutting to disguise the fact that the actual steps are fairly bland. The score, a series of pop songs with the odd instrumental number by Mark Ronson and Andrew Wyatt, had a seductive kind of poignancy even without Boy George, who sang in the 2012 premiere. I couldn't catch all the words, but there was mingled longing and anger at an absent lover, even the threat of violence. Little of it was picked up in the series of interchangeable duets which forms the middle of the work; my interest only revived towards the end, when Eric Underwood appeared looking both splendid and ridiculous in a kind of black Wonderwoman costume and pointe shoes (pictured above left) and the singers crooned "I need somebody to be nice, I need somebody to love me", and all was briefly daft and funny and fun.

There are moments of fun, of swagger, of emotion, of shock and of power in McGregor's work, but - at least in his Royal Ballet oeuvre - they are all too few and far between. He choreographs in the same way he talks about choreography: using too many words to say very little. It's a damned shame for him and the Royal Ballet. Dance can be so much more than this.

- The Royal Ballet perform Chroma/Multiverse/Carbon Life at the Royal Opera House until 19 November.

- Read more dance reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Onegin, Royal Ballet review - a poignant lesson about the perils of youth

John Cranko was the greatest choreographer British ballet never had. His masterpiece is now 60 years old

Onegin, Royal Ballet review - a poignant lesson about the perils of youth

John Cranko was the greatest choreographer British ballet never had. His masterpiece is now 60 years old

Northern Ballet: Three Short Ballets, Linbury Theatre review - thrilling dancing in a mix of styles

The Leeds-based company act as impressively as they dance

Northern Ballet: Three Short Ballets, Linbury Theatre review - thrilling dancing in a mix of styles

The Leeds-based company act as impressively as they dance

Best of 2024: Dance

It was a year for visiting past glories, but not for new ones

Best of 2024: Dance

It was a year for visiting past glories, but not for new ones

Nutcracker, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - Tchaikovsky and his sweet tooth rule supreme

New production's music, sweets, and hordes of exuberant children make this a hot ticket

Nutcracker, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - Tchaikovsky and his sweet tooth rule supreme

New production's music, sweets, and hordes of exuberant children make this a hot ticket

Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake, New Adventures, Sadler's Wells review - 30 years on, as bold and brilliant as ever

A masterly reinvention has become a classic itself

Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake, New Adventures, Sadler's Wells review - 30 years on, as bold and brilliant as ever

A masterly reinvention has become a classic itself

Ballet Shoes, Olivier Theatre review - reimagined classic with a lively contemporary feel

The basics of Streatfield's original aren't lost in this bold, inventive production

Ballet Shoes, Olivier Theatre review - reimagined classic with a lively contemporary feel

The basics of Streatfield's original aren't lost in this bold, inventive production

Cinderella, Royal Ballet review - inspiring dancing, but not quite casting the desired spell

A fairytale in need of a dramaturgical transformation

Cinderella, Royal Ballet review - inspiring dancing, but not quite casting the desired spell

A fairytale in need of a dramaturgical transformation

Comments

Really interesting review.

Thank you, Rachel, you are

Thank you, Rachel, you are quite right, and I did know it - just a slip of the "pen" with similar-sounding names. Thank you for spotting; it has been corrected.