Citizen Jane review - portrait of a New York toughie | reviews, news & interviews

Citizen Jane review - portrait of a New York toughie

Citizen Jane review - portrait of a New York toughie

BBC Four documentary on the remarkable Jane Jacobs, scourge of New York town planners

When you’re next strolling through Washington Square Park, or SoHo, or the West Village, you can thank Jane Jacobs that those New York neighbourhoods have survived (though she'd blanch at the price of real estate). Four-lane highways almost dissected and ruined them in the mid-Fifties, but her grass-roots activism saved those higgledy-piggledy streets.

Vanity Fair writer and director Matt Tyrnauer’s documentary Citizen Jane: Battle for the City (BBC Four) – his second feature after Valentino: The Last Emperor, an unlikely predecessor – focuses on Jacobs and her arch-rival, power-broker Robert Moses (pictured below), who hated the messiness of places like Greenwich Village (he saw sidewalks as foolish). Moses wanted to designate diverse neighbourhoods as slums – “Cut out the cancer” – and replace them with sterile housing projects and superhighways under the profitable umbrella of urban renewal.

Thou Shalt Drive was his first commandment, though he never learned himself. There are shades of Trump in his monomania. “You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs,” he proclaims contemptuously. If people objected to having their homes destroyed in order to make room for his roads and high-rises, well, they were just ill-informed. And poor, and probably black, as James Baldwin observes in the film.

It’s fascinating to behold such White Male hubris in action, and Jacobs, whose centenary was last year, was his opposite. A forceful contrast, but sometimes you wish for a bit more nuance. She bicycled around the Village, understood the soul of a city and how it worked – it may look chaotic but there is an ecosystem, a “street ballet” full of interconnections – at a time when homogenising post-war modernism, with its obsession with wiping the slate clean, was all the rage. "There must be eyes upon the street,” she wrote in her influential book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, because that makes it safe; if there are unused areas, as in many public spaces around high-rises, it’s dangerous. Diversity makes sense. This was heresy at the time. The film tends to generalise in its first half with too many experts, Saskia Sassen and Ed Koch among them, and too much footage of nameless buildings being bulldozed. It's best when it concentrates on specifics such as Jacobs’s fight for Washington Square. In the early Fifties Moses wanted to build an extension to Fifth Avenue, a four-lane sunken highway that would run through the park. He’d already hacked his way through the Bronx with the Cross-Bronx Expressway, resulting in the decimation of a neighbourhood that’s never fully recovered, but in his plans for the Village he hadn’t bargained on Jacobs, who, though not formally trained, wrote on urban planning for Architectural Forum (she started off writing for Vogue) and lived near Washington Square on Hudson Street.

The film tends to generalise in its first half with too many experts, Saskia Sassen and Ed Koch among them, and too much footage of nameless buildings being bulldozed. It's best when it concentrates on specifics such as Jacobs’s fight for Washington Square. In the early Fifties Moses wanted to build an extension to Fifth Avenue, a four-lane sunken highway that would run through the park. He’d already hacked his way through the Bronx with the Cross-Bronx Expressway, resulting in the decimation of a neighbourhood that’s never fully recovered, but in his plans for the Village he hadn’t bargained on Jacobs, who, though not formally trained, wrote on urban planning for Architectural Forum (she started off writing for Vogue) and lived near Washington Square on Hudson Street.

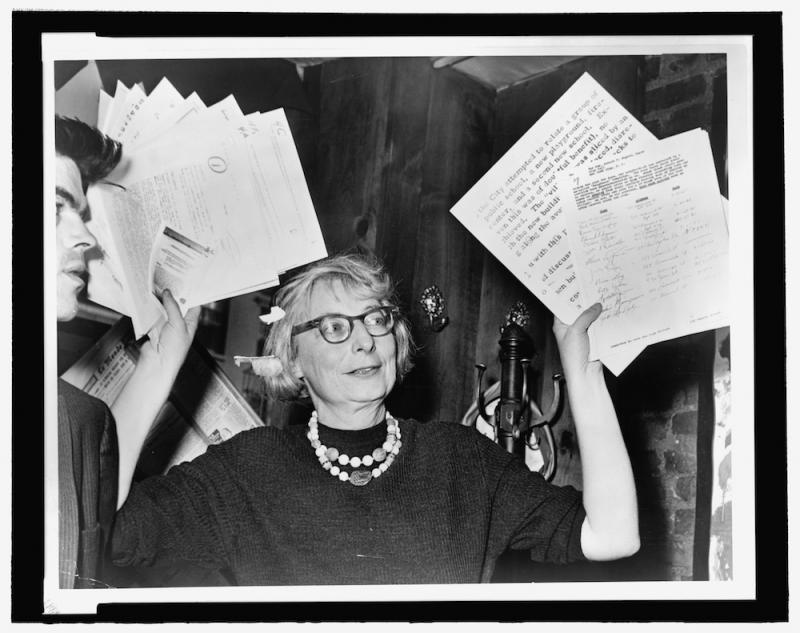

She was a brilliant strategist and community organiser. Moses dismissed the resistance as just “a bunch of mothers” though Eleanor Roosevelt (great footage of her speech, delivered in an exotic patrician accent), Susan Sontag and Margaret Mead were all on board, and in 1958, after years of public protests and petitions, Moses’s plan was quashed. Newspapers published photos of Jacobs’s small daughters in a ribbon-tying ceremony in the park, the opposite of his endless ribbon-cutting. A few years later, she pulled it out of the hat again with her successful opposition to his next scheme, that of building a Lower Manhattan Expressway that would have destroyed SoHo and Little Italy. She was arrested for disorderly conduct along the way.

The pre-war Moses was, briefly, a progressive and a park-planner (Jones Beach, built in the Twenties, with some art-deco flourishes among the parking fields and bathhouses, is one of his projects) before profiteering and vested interests got the better of him. Le Corbusier, who took a god-like view of cities, preferring to see them from a plane, was a huge influence, but Moses and other American modernists got him slightly wrong – Corb’s towers were for offices, with lower buildings around them for living in. But it was all too easy to build ‘em high and cheap. "This is not the rebuilding of cities, this is the sacking of cities," wrote Jacobs, lamenting the low-income projects that became more crime-ridden than the slums they were supposed to replace.

Modernist planning on the Corbusier model decimated many American cities – Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, Denver among them – and the film shows the towers going up and, decades later, being dynamited down. China – “like Moses on steroids,” says Saskia Sassen – is using the US model now, with its rows of identical concrete blocks. Urbanisation is happening on an unprecedented scale and the struggle for a city's soul continues. But it’s Jane Jacobs’ vision you come away admiring, as well as her determination to fight back.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment