Closed Curtain | reviews, news & interviews

Closed Curtain

Closed Curtain

Allusive meditation on creativity from banned Iranian director Jafar Panahi

Any consideration of Iranian director Jafar Panahi’s Closed Curtain will inevitably be through the prism of how it was made, and the director’s current position in his native country. It’s his second work, after This Is Not a Film from 2011, to be made despite the 2010 prohibition from the Iranian authorities that (along with a range of other curtailments of his freedom) the director should not engage in cinema for a period of 20 years.

It’s rather more ambitious – though not in terms of its setting, the interiors of a single house on the shore of the Caspian – than the relatively simple premise behind This Is Not a Film. Closed Curtain is a more elliptical work, which after the first hour of its 100 minute-plus running time changes register in a way that may disappoint, though the more poetic, associative direction it takes at that point certainly remains in the memory, as does a sense of melancholy that goes beyond any of its immediate circumstances.

There’s a sense of fear in the air, unspoken rather than palpable

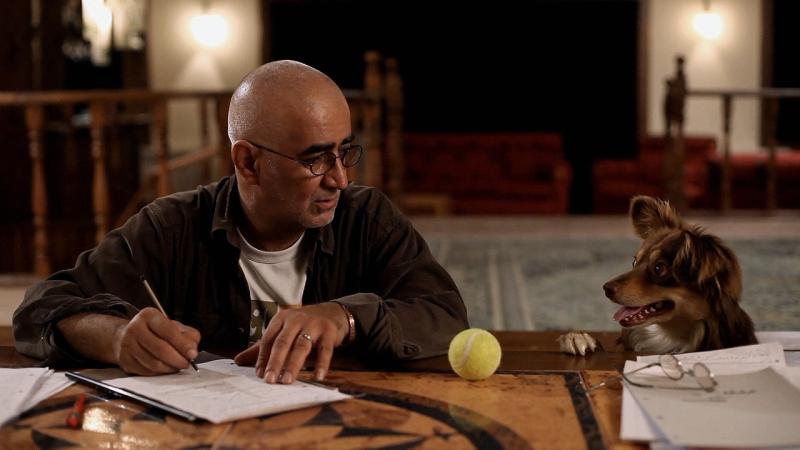

Mohammad Reza Jahanpanah’s necessarily simple cinematography nails its colours to the mast straightaway with a four-minute static shot through the metal grilles of a large window. We barey see the landscape outside, though gusts of wind suggest remoteness, as a single figure gets out of a car, unloads his bags and brings them into the house. That sense of rather gloomy isolation – a downbeat existence, the sparsely furnished building, no musical score – lightens immediately when a dog (screen name, Boy) is released from one of the bags: his presence will brighten considerably the scenes through which he will scamper. (Kamboziya Partovi, himself a film director and credited as co-director here, as the lead character, with Boy, main picture.)

Given that the first thing the new arrival, whose name we never learn, does is to black out all the windows with thick fabric brings home his concern with concealment. (The symbolic relevance of man and dog sitting looking at the large window transformed into a black, blank screen to Panahi’s own position won’t be missed). There’s a sense of fear in the air, unspoken rather than palpable, which receives an extra dimension when a television (being watched only by the dog!) cuts suddenly to scenes of canine slaughter, an allusion, though exaggerated, to such real-life campaigns against the animals in Iran. We inevitably assume, knowing the wider circumstances, that Panahi is depicting his homeland, though precedents from any Soviet-era or other totalitarian society would fit as well. (On the former front, another recent Iranian film, Mohammad Rasoulof’s Manuscripts Don’t Burn from 2013, brought home such resemblances rather brilliantly: coincidence then that Partovi’s character here turns out to be a screenwriter?)

When a young couple appears mysteriously, the hint of danger increases, with elements of quasi-thriller appearing: their story is that they’ve escaped a nearby illegal party that was busted by the police, and the brother asks to leave his sister Melika (Maryam Moghadam, pictured below) there while he locates friends and assistance. The ongoing interaction between the two is complicated, and certainly draws on the Theatre of the Absurd. He’s been warned that she has a “knack for suicide” (and her scars suggest it), but Melika also seems to know rather more about the writer than she might (suggesting she’s not who she claims to be). She also plays up to his self-doubts, later tearing down the curtains as she argues that death may be better that continuing concealment, and coming out with the clearest allusion to the wider real-life situation, “Why keep on writing? Who’ll make it into a movie?”

When a young couple appears mysteriously, the hint of danger increases, with elements of quasi-thriller appearing: their story is that they’ve escaped a nearby illegal party that was busted by the police, and the brother asks to leave his sister Melika (Maryam Moghadam, pictured below) there while he locates friends and assistance. The ongoing interaction between the two is complicated, and certainly draws on the Theatre of the Absurd. He’s been warned that she has a “knack for suicide” (and her scars suggest it), but Melika also seems to know rather more about the writer than she might (suggesting she’s not who she claims to be). She also plays up to his self-doubts, later tearing down the curtains as she argues that death may be better that continuing concealment, and coming out with the clearest allusion to the wider real-life situation, “Why keep on writing? Who’ll make it into a movie?”

Their semi-sparring is strangely mesmeric, if in a rather abstract way, but it’s more than disrupted tonally by the appearance just before the hour mark of Panahi himself, as the dramatic register transfers allegiances to Pirandello and his Six Characters… Posters from international releases of his films are revealed behind more curtains on the villa’s walls, while the exterior landscape changes to a brighter season. The director’s caught up in the details of his own life, with workers in to mend the broken window left by the earlier action (one apologises for not wishing to have his picture taken with the director). There’s comfort in such everyday interactions, however, particularly with a neighbour who keeps an eye on the house, and his wife who brings Panahi food. The wisdom of such “simple” folk comes through strongly, with the male visitor counselling that things will improve and that anyway, “Life is but memories, some bitter, some sweet”. (A hint of Tarkovsky there too, with images drawn by the director from a past combining what may be childhood or may be cinematic legacy?).

Further interactions between those we now understand to have been Panahi’s characters-in-progress – all sorts of different kinds of filming punctuate the film as well – are more elusive, occasionally laced with humour. His protagonists (in the double sense, now) worry that Panahi can write them out – “he killed you off,” the woman says at one point – or wonder how they can reassert their presence; the appearance of Melika’s relatives in the “real” world blurs matters further. “You can’t steal reality,” we hear at one point, but perhaps you can, as one moment suggests that his characters can somehow take over Panahi’s script, even influence the director’s own fate. It’s interaction, rather than control across the fourth wall.

Further interactions between those we now understand to have been Panahi’s characters-in-progress – all sorts of different kinds of filming punctuate the film as well – are more elusive, occasionally laced with humour. His protagonists (in the double sense, now) worry that Panahi can write them out – “he killed you off,” the woman says at one point – or wonder how they can reassert their presence; the appearance of Melika’s relatives in the “real” world blurs matters further. “You can’t steal reality,” we hear at one point, but perhaps you can, as one moment suggests that his characters can somehow take over Panahi’s script, even influence the director’s own fate. It’s interaction, rather than control across the fourth wall.

There’s a pervasive melancholy here, with the suggestion that both sides in the author-character relationship are lonely, unfulfilled without one another, hinting, as Panahi himself finally closes the grilles (main picture, above) before departure that his personages are left behind – The Cherry Orchard, anyone? – locked away to live a life we will never see. If there’s a coda to this unsettling, if not completely satisfactory work (which took Best Screenplay prize at the Berlinale in 2013), it’s in the fact that Panahi has gone on to make a third film despite his unchanging circumstances and lack of freedom: Taxi Tehran, winner of the Golden Bear at the Berlinale this year, will be released in the UK next month.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Closed Curtain

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Blu-ray: Yojimbo / Sanjuro

A pair of Kurosawa classics, beautifully restored

Blu-ray: Yojimbo / Sanjuro

A pair of Kurosawa classics, beautifully restored

Mr Burton review - modest film about the birth of an extraordinary talent

Harry Lawtey and Toby Jones excel as the future Richard Burton and his mentor

Mr Burton review - modest film about the birth of an extraordinary talent

Harry Lawtey and Toby Jones excel as the future Richard Burton and his mentor

Restless review - curse of the noisy neighbours

Assured comedy-drama about an ordinary Englishwoman turned vigilante

Restless review - curse of the noisy neighbours

Assured comedy-drama about an ordinary Englishwoman turned vigilante

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Four Mothers review - one gay man deals with three extra mothers

Darren Thornton's comedy has charm but is implausible

Four Mothers review - one gay man deals with three extra mothers

Darren Thornton's comedy has charm but is implausible

Misericordia review - mushroom-gathering and murder in rural France

A deadpan comedy-thriller from the director of ‘Stranger by the Lake’

Misericordia review - mushroom-gathering and murder in rural France

A deadpan comedy-thriller from the director of ‘Stranger by the Lake’

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer on his apocalyptic musical 'The End'

The documentary director talks about his ominous first fiction film and why its characters break into song

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer on his apocalyptic musical 'The End'

The documentary director talks about his ominous first fiction film and why its characters break into song

DVD/Blu-ray: The Substance

French director Coralie Fargeat on the making of her award-winning body-horror movie

DVD/Blu-ray: The Substance

French director Coralie Fargeat on the making of her award-winning body-horror movie

A Working Man - Jason Statham deconstructs villains again

A meandering vehicle for the action thriller star

A Working Man - Jason Statham deconstructs villains again

A meandering vehicle for the action thriller star

The End review - surreality in the salt mine

Unsettling musical shows the lengths we go to avoid the truth

The End review - surreality in the salt mine

Unsettling musical shows the lengths we go to avoid the truth

La Cocina review - New York restaurant drama lingers too long

Struggles of undocumented immigrants slaving in a Times Square kitchen

La Cocina review - New York restaurant drama lingers too long

Struggles of undocumented immigrants slaving in a Times Square kitchen

Blu-ray: Lifeforce

Tobe Hooper's frenzied, far out space sex vampire epic

Blu-ray: Lifeforce

Tobe Hooper's frenzied, far out space sex vampire epic

Add comment