There’s an episode in the first season of Mad Men in which the ad execs of Sterling Cooper brainstorm a campaign for Richard Nixon, just prior to the 1960 presidential election. Dramatic irony being what it is, it’s a rare opportunity to watch our anti-heroes working on a pitch (based chiefly around smear tactics) that is predestined to fail. By contrast, Pablo Larraín’s No chronicles how a team of ad men in 1980s Chile, led by Gael Garcia Bernal’s maverick René, put together a campaign to topple a dictator that we know will succeed against all odds.

No is the third film in a loose trilogy from Larraín, whose first two features Tony Manero and Post Mortem both took place during the darkest days of the Pinochet regime. Now it’s 1988, and the referendum to decide whether Pinochet will rule for another eight years is being held. Both the "Yes" and the "No" campaigns are entitled to 15 minutes of television advertising every night in the month leading up to the vote. Bernal’s much-in-demand René is enlisted to oversee the "No" campaign, which is widely regarded as a doomed charade that will only serve to legitimise the Pinochet government.

The Mad Men comparisons have been ubiquitous - it’s even referenced in the film’s tagline - and yet aside from that early Nixon vs Kennedy arc, the two have very little to do with one another. Where that series revels frequently in cynicism, and in the essentially hollow rewards of advertising as a career, No pulses with quiet passion.

The Mad Men comparisons have been ubiquitous - it’s even referenced in the film’s tagline - and yet aside from that early Nixon vs Kennedy arc, the two have very little to do with one another. Where that series revels frequently in cynicism, and in the essentially hollow rewards of advertising as a career, No pulses with quiet passion.

Bernal gives a measured and fascinating performance as a man whose conflict comes less from a Draper-esque wandering eye and dark past than from genuine concerns for his own political integrity and his family’s safety. A subtly tense thread is established as the "No" campaign begins to gather steam and the Pinochet regime resort to scare tactics against René and his team, but Larraín doesn’t spend much energy on this and overall seems less interested in evoking a mood of dystopian fear than in chronicling both campaigns in painstaking, largely absorbing detail.

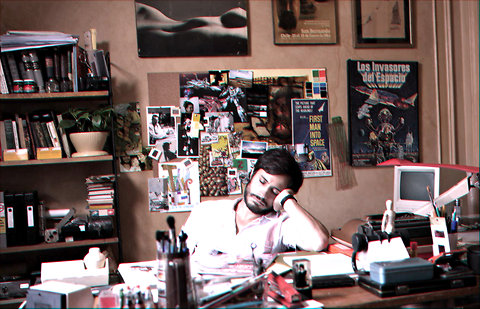

No is visually drab by design, filmed through a period-appropriate lens that establishes a sense of this as documentary more than storytelling; there are almost no wide shots, Larraín’s camera in perpetual close-up on faces, screens, logos. What’s presumably less intentional is the intermittently flat characterisation – René’s subdued efforts to reconnect with his wife (Antonia Zegers) and young son (Pascal Montero) never resonate emotionally, and there’s a general sense of these characters as archetypes rather than people.

Nonetheless, this is a rigorously drawn account of a remarkable coup that delves shrewdly into the machinations of political marketing.

Add comment