We Were Here | reviews, news & interviews

We Were Here

We Were Here

As a new documentary is released, a writer who was also there remembers San Francisco at the advent of AIDS

The advent of AIDS tore through San Francisco’s Castro district, the heart of the city’s gay community, with the same ferocity as Hurricane Katrina hitting New Orleans’s Ninth Ward.

Now a new documentary, We Were Here: Voices from the AIDS Years in San Francisco, conveys the impact of the advent of the “gay plague” through archival footage and the testimony of five eyewitnesses: Eileen, a nurse with seemingly bottomless reserves of compassion and practicality, who volunteered to work on SF General’s AIDS ward in the early days when patients were virtually quarantined and who later set up early clinical trials; Paul, a hard partier who became a political organiser campaigning for spending on treatment and research; Daniel, a successful artist who, HIV-positive himself, overcame crippling personal grief to organise benefit art shows; Guy, whose vantage point from his flower stall in the Castro allowed him to observe the impact on the community on street level; and Ed, whose aversion to casual sex and ineptitude at cruising probably saved his life, while his sensitivity and empathy made him an ideal counsellor to the sick and dying.

By 1980 the snake was in gay paradise

Grounding the story in these individual experiences saves the film from being all gloom and doom; instead, rather like The Secret Millionaire, it leaves one awed and inspired by the quiet heroism of ordinary people responding to a desperate situation with extraordinary selflessness and positivity. And if this sounds like it might all be a bit po-faced, this is the San Francisco gay community we’re talking about, so there’s lots of earthy humour and anger.

Directors David Weissman and Bill Weber wisely avoid any editorialising and let the personal stories speak for themselves. And what stories they are: men days away from death dragging themselves to Washington to demonstrate for more research funding though barely able to walk; the father who told Ed that finding out his son was gay was worse than the news of the son’s imminent death; Eileen asking patients to whom she’d grown close to donate their eyes for research into an aspect of the disease that causes blindness (CMV retinitis) and then having to collect their eyes from the morgue; Daniel signing up for a trial of an early experimental treatment his boyfriend, an immunologist, knew about, quitting because the drug made him so nauseous, and then losing his boyfriend (who died along with all the other 80 patients on the trial), followed by his closest friend two weeks later; and Guy seeing a passer-by the picture of health on a bicycle, then walking with a cane, then in a wheelchair, and finally, after combination therapy had been developed, back on a bicycle.

Directors David Weissman and Bill Weber wisely avoid any editorialising and let the personal stories speak for themselves. And what stories they are: men days away from death dragging themselves to Washington to demonstrate for more research funding though barely able to walk; the father who told Ed that finding out his son was gay was worse than the news of the son’s imminent death; Eileen asking patients to whom she’d grown close to donate their eyes for research into an aspect of the disease that causes blindness (CMV retinitis) and then having to collect their eyes from the morgue; Daniel signing up for a trial of an early experimental treatment his boyfriend, an immunologist, knew about, quitting because the drug made him so nauseous, and then losing his boyfriend (who died along with all the other 80 patients on the trial), followed by his closest friend two weeks later; and Guy seeing a passer-by the picture of health on a bicycle, then walking with a cane, then in a wheelchair, and finally, after combination therapy had been developed, back on a bicycle.

These recollections, all the more moving for their lack of sentimentality or self-dramatisation, bring to mind Steve Humphries’ BBC oral history of the last surviving veterans of the First World War. Indeed, I remember walking down Castro Street in 1986 and thinking this was what Paris in 1919 must have been like - lots of wan young men tottering down the street leaning on canes, while even the physically untouched had the stunned look of those who had seen too much death. The ghosts were practically palpable.

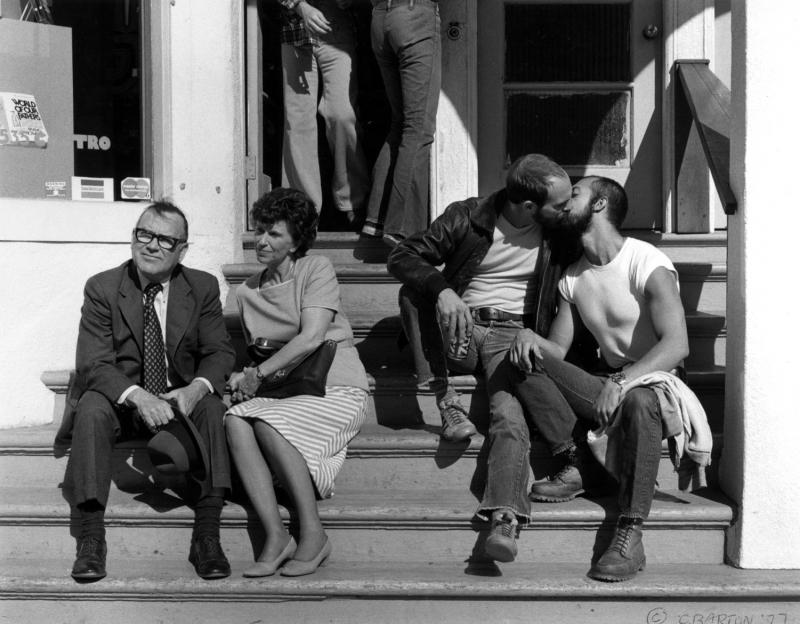

Ten years before the street had been sizzling with the energy of thousands of boys and men who had fled small towns across America to come roaring out of the closet with a vengeance, creating an atmosphere of exuberance and cultural energy (captured in Weissman and Weber’s previous film on The Cockettes, a 1970s SF theatrical collective that specialised in what is best described as spectacular pantos). However, liberation soon shaded over into libertinism. As Paul says in the film, “The feeling was if gay sex is good, lots of gay sex is better,” and an aspect of the gay scene became characterised by nameless, and occasionally faceless (with participants on opposite sides of a wall), encounters in bathhouses and clubs. (At the time it occurred to me that this was what many straight men would like the heterosexual scene to be like if they weren’t hampered by women asking, in the words of the song, “But will you love me tomorrow?”)

Ten years before the street had been sizzling with the energy of thousands of boys and men who had fled small towns across America to come roaring out of the closet with a vengeance, creating an atmosphere of exuberance and cultural energy (captured in Weissman and Weber’s previous film on The Cockettes, a 1970s SF theatrical collective that specialised in what is best described as spectacular pantos). However, liberation soon shaded over into libertinism. As Paul says in the film, “The feeling was if gay sex is good, lots of gay sex is better,” and an aspect of the gay scene became characterised by nameless, and occasionally faceless (with participants on opposite sides of a wall), encounters in bathhouses and clubs. (At the time it occurred to me that this was what many straight men would like the heterosexual scene to be like if they weren’t hampered by women asking, in the words of the song, “But will you love me tomorrow?”)

But by 1980 the snake was in gay paradise. Paul recalls a homemade poster in the window of a Castro pharmacy, illustrated with disturbing photos of the writer’s own lesions, warning others to watch out for them. Within months, men who looked like famine victims were a common sight. Given the overlap between friendship and sex in gay circles, many, like Daniel, lost almost all their close friends, leaving the survivors emotionally numb. I was perplexed when a friend of mine showed almost no response after someone I knew he had cared about died. “I’ve crossed out almost all the names in my address book,” he said. “After you’ve been to 50 funerals in a year, one more doesn’t matter that much.”

The obituary page of the Bay Area Reporter, a weekly aimed at the gay readership, grew and grew. One of the most powerful images in the film is an assemblage of the BAR’s obituary photos. With the search for a cure a low priority and some religious denominations suggesting the victims had brought it on themselves, voluntary support organisations proliferated, buying groceries for house-bound invalids, taking care of pets while owners were hospitalised, lobbying for partners to be considered next of kin, or, like the organisation that trained Ed, simply providing people to listen. As the film points out, a community that a year before had been characterised by hedonism and a superficial worship of the body beautiful was now devoting itself to giving sponge baths, cleaning up sick, and generally providing a family for those who had been abandoned by their own.

The obituary page of the Bay Area Reporter, a weekly aimed at the gay readership, grew and grew. One of the most powerful images in the film is an assemblage of the BAR’s obituary photos. With the search for a cure a low priority and some religious denominations suggesting the victims had brought it on themselves, voluntary support organisations proliferated, buying groceries for house-bound invalids, taking care of pets while owners were hospitalised, lobbying for partners to be considered next of kin, or, like the organisation that trained Ed, simply providing people to listen. As the film points out, a community that a year before had been characterised by hedonism and a superficial worship of the body beautiful was now devoting itself to giving sponge baths, cleaning up sick, and generally providing a family for those who had been abandoned by their own.

From 1980 to the mid-1990s, when a workable combination therapy finally brought the virus under control, more than 15,000 gay men died. But eventually the BAR was able to run the huge headline “No Obits” and, although the time-bomb of HIV continued to take a toll, the storm had largely passed, at least in San Francisco and the developed world. Meanwhile, the same deadly mixture of prejudice and the silence it encourages, underfunded medical care, and inadequate access to drugs means that it still rages through parts of Africa. Even in the West, as the devastating impact of AIDS recedes into the past, younger people are becoming more casual about safe sex. This powerful, affecting film should help ensure that by remembering the past we will not be condemned to repeat it.

- We Were Here opens on Friday at the ICA

- Ellin Stein's That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick: The National Lampoon and the Comedy Insurgents Who Captured the Mainstream will be published by Norton in 2012

Watch the trailer to We Were Here

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Restless review - curse of the noisy neighbours

Assured comedy-drama about an ordinary Englishwoman turned vigilante

Restless review - curse of the noisy neighbours

Assured comedy-drama about an ordinary Englishwoman turned vigilante

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Four Mothers review - one gay man deals with three extra mothers

Darren Thornton's comedy has charm but is implausible

Four Mothers review - one gay man deals with three extra mothers

Darren Thornton's comedy has charm but is implausible

Misericordia review - mushroom-gathering and murder in rural France

A deadpan comedy-thriller from the director of ‘Stranger by the Lake’

Misericordia review - mushroom-gathering and murder in rural France

A deadpan comedy-thriller from the director of ‘Stranger by the Lake’

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer on his apocalyptic musical 'The End'

The documentary director talks about his ominous first fiction film and why its characters break into song

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer on his apocalyptic musical 'The End'

The documentary director talks about his ominous first fiction film and why its characters break into song

DVD/Blu-ray: The Substance

French director Coralie Fargeat on the making of her award-winning body-horror movie

DVD/Blu-ray: The Substance

French director Coralie Fargeat on the making of her award-winning body-horror movie

A Working Man - Jason Statham deconstructs villains again

A meandering vehicle for the action thriller star

A Working Man - Jason Statham deconstructs villains again

A meandering vehicle for the action thriller star

The End review - surreality in the salt mine

Unsettling musical shows the lengths we go to avoid the truth

The End review - surreality in the salt mine

Unsettling musical shows the lengths we go to avoid the truth

La Cocina review - New York restaurant drama lingers too long

Struggles of undocumented immigrants slaving in a Times Square kitchen

La Cocina review - New York restaurant drama lingers too long

Struggles of undocumented immigrants slaving in a Times Square kitchen

Blu-ray: Lifeforce

Tobe Hooper's frenzied, far out space sex vampire epic

Blu-ray: Lifeforce

Tobe Hooper's frenzied, far out space sex vampire epic

Brief History of a Family review - glossy Chinese psychological thriller feels shallow

Immaculately crafted family drama aimed at international art house audiences

Brief History of a Family review - glossy Chinese psychological thriller feels shallow

Immaculately crafted family drama aimed at international art house audiences

Two Strangers Trying Not to Kill Each Other review - a portrait of photographer Joel Meyerowitz

Scenes from a seemingly picture-perfect marriage

Two Strangers Trying Not to Kill Each Other review - a portrait of photographer Joel Meyerowitz

Scenes from a seemingly picture-perfect marriage

Add comment